Janis Hughes is dying of cancer, but she fully intends to leave this world with a big smile on her face, happily anticipating whatever comes next.

It’s not because she thinks heaven awaits. Hughes, 67, isn’t sure exactly what happens when we die. It’s because two trips with psilocybin, a hallucinogenic substance found in “magic mushrooms,” eased the end-of-life panic that consumed her after she was told in 2022 that she had two years left to live.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

“The emotions I experienced in the wake of my diagnosis were like none I’d ever felt,” says the retired translator from Winnipeg. “I’ve dealt with depression for most of my adult life, but this was different. Every time I saw a friend, I wondered if it would be our final goodbye. I feared every experience I had would be my last. My mind was like a gerbil on a wheel, repeating the same phrase over and over: I’m dying. I’m dying. I’m dying.”

A significant body of research shows that when administered in a therapeutic setting, psilocybin can disrupt negative thought patterns for those suffering from anxiety, depression, PTSD and substance abuse by potentially altering the brain’s pathways. It is under a great deal of scrutiny for its use in easing the terror of death and the anguish of mental health disorders. But researchers have also documented that it can act on the brain to induce mystical experiences that can lead to greater spiritual well-being.

Some people, including Rick Doblin, founder and president of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, go much further. Doblin is credited as a key figure in the psychedelic revolution, and he thinks these substances may be able to transform humanity and maybe even save the planet. In a 2021 interview with GQ magazine, he predicted there would be thousands of legal psychedelic clinics in the United States over the next few decades, which will help produce “a spiritualized humanity that has dealt with all the crises.” Psychedelics will be “the antidote to genocide, to environmental destruction.”

Is it hype or hope? Can psychedelics, historically known as recreational party drugs, really serve to improve the human experience? Governments, scientists, healthcare providers, spiritual leaders and individuals like Hughes believe they may have the power to change not only the way we die, but also how we live.

***

The allure of psychedelics has permeated popular culture. Michael Pollan’s bestselling book How to Change Your Mind, which looks at how they are being used to provide relief to people suffering from difficult-to-treat conditions, was made into a Netflix series. Documentaries such as Fantastic Fungi and Dosed: The Trip of a Lifetime show the transformative effects made possible by magic mushrooms. Prince Harry has shared that he used mushrooms to cope with the grief of losing his mother.

American federal institutions are lining up to develop and review the substance. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has designated psilocybin as a breakthrough therapy for depression that can’t be treated other ways and major depressive disorder, while the U.S. National Institutes of Health has ruled that it has a low potential for both addiction and fatal side effects. Worldwide, the psychedelic market is expected to exceed US$8 billion by 2028, according to some estimates, as these substances become more widely accepted and legalized.

In psychiatry, psychedelics are being touted as a paradigm shifter. In 2022, Alberta ruled that psychiatrists or physicians in consultation with a psychiatrist can prescribe psychedelic drugs, and Australia became the first country to do the same, for certain conditions. Oregon and Colorado have loosened restrictions on psilocybin, and more states are expected to follow suit. The Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research in Baltimore, Md., and the Center for Psychedelic Medicine at New York University are getting tens of millions of dollars in research money to examine the benefits of psychedelics.

In Canada, psilocybin is illegal for almost all personal use. The federal government is funding a handful of clinical psilocybin trials and has licensed several suppliers to provide psilocybin for those trials, but Health Canada says that more research is required to prove the safety and efficacy of psilocybin before it allows wider access.

Some patients have been able to get permission to use psilocybin from Health Canada through special exemptions, including as an emergency treatment for people who are dying. From 2020 to 2022, Health Canada granted about 50. The rules changed in 2022 so that only physicians and researchers could apply for the substance on behalf of their patients or for use in clinical trials. At press time, Health Canada had granted around 200 exemptions since then. But some patients who want psilocybin can’t find a physician to apply on their behalf.

More on Broadview:

At the same time, the grey market is thriving. Retail outlets are proliferating across the country. These stores are routinely shut down by police, only to pop up again, operating in an unregulated zone, much as cannabis shops did before pot was legalized. I can attest to how easy it is to get psilocybin. I experimented with dosing myself and wrote about my experience for Broadview in 2017.

As well, private Canadian clinics such as Field Trip Health and Numinus are offering legal guided sessions in a medically supervised setting with ketamine, which has psychedelic-like effects, while luxurious programs such as Dimensions in Ontario and the Journeymen Collective in British Columbia are charging thousands for “bespoke” group sessions with cannabis and psilocybin, respectively. The latter are in secret locations.

Many individual therapists across Canada (some of them operating underground) are offering mushrooms to their clients. Hughes, for example, paid a psychedelic therapist $2,500 for two six-hour psilocybin trips after she failed to get an exemption from Health Canada allowing her legal psilocybin. The trips had a dramatic impact, helping her better understand and forgive her long-dead parents and come to terms with the painful memories of enduring years of molestation by a family friend. She came to accept that her life will be much shorter than she had hoped.

“I no longer fear dying, which is an enormous gift because I am now able to fully enjoy life however much time I have left,” she says. “It did more than stop the end-of-life anxiety — it has been liberating and helped me resolve childhood trauma. It’s been phenomenal.”

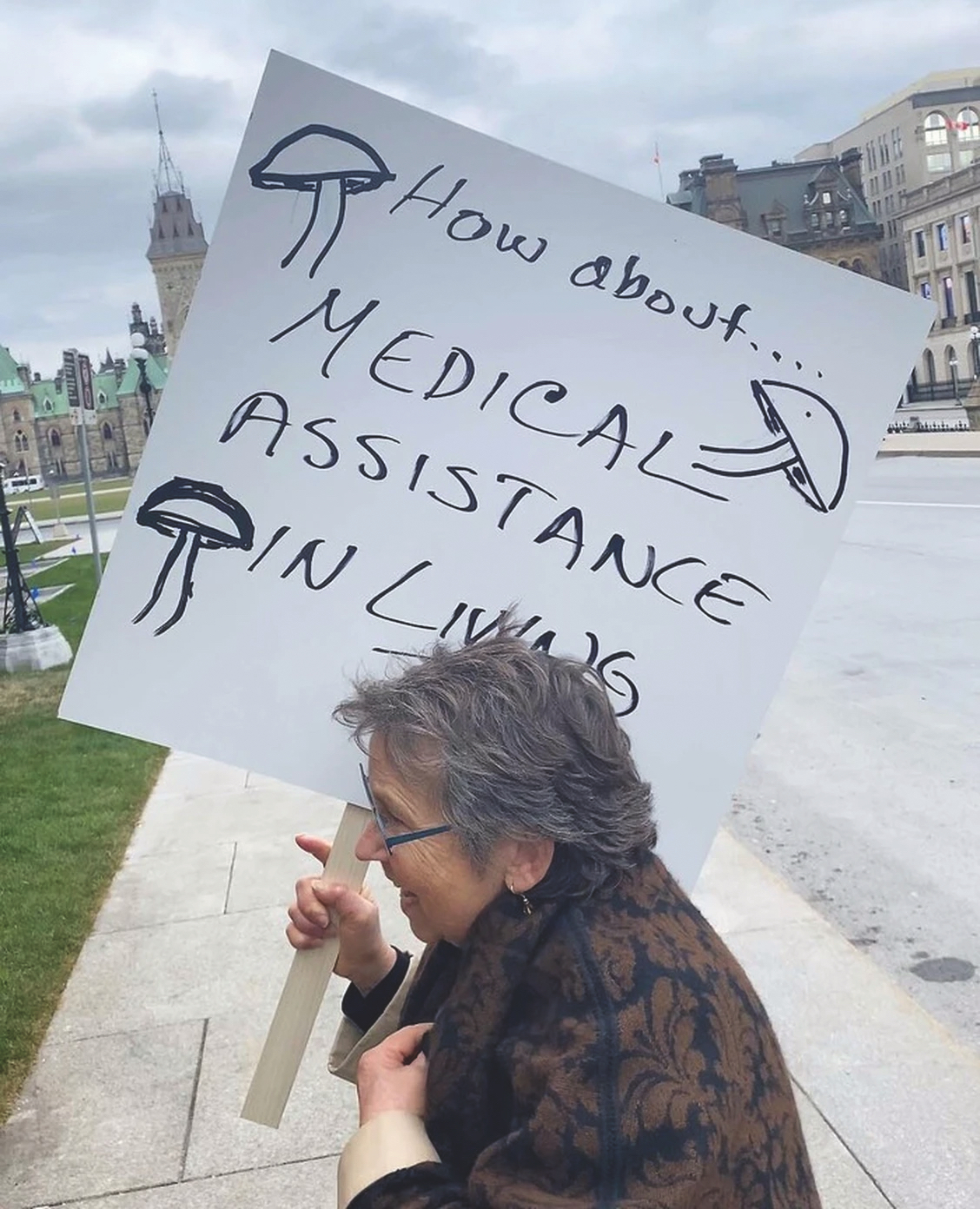

Hughes wants other Canadians to have wider access to psilocybin. She is one of eight plaintiffs in a constitutional challenge against the federal government that argues the inaccessibility of psilocybin therapy violates the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

She is backed in her advocacy for psilocybin by other patients, palliative care physicians, nurses, therapists and religious leaders who argue that current government roadblocks to psilocybin are causing unnecessary harm to those struggling with mental anguish at the end of their lives.

And the public is with her, too. Nearly four in five Canadians believe psilocybin is an acceptable choice for dying patients who are in existential distress, according to a survey of 2,800 people conducted by a team of researchers in Quebec, published in January in the journal Palliative Medicine.

Hughes has told CBC that “it’s absurd” to withhold this treatment from people like her who are dying. “They insist it’s for my safety.…I am a terminal patient with a near-term expiry date.”

What outrages Hughes most is that it would be easier to receive government approval to end her life with medical assistance in dying (MAID) than be granted the right to live out her final days with some measure of tranquility by legally accessing psilocybin: “It feels cruel, thoughtless,” she says.

Dave Phillips, a registered clinical counsellor in Abbotsford, B.C., agrees with Hughes. He trains healthcare providers in the use of psilocybin-assisted therapy at TheraPsil, a non-profit coalition based in British Columbia that advocates for legal access to psilocybin for Canadians in medical need. The coalition has trained more than 500 health-care providers, about a quarter of them physicians. “When someone applies for MAID, their physician should have the option to let them know about mushroom therapy,” he says.

***

But how helpful could psilocybin be as we edge cases of advanced cancer, says Dr. Paul Daeninck, an oncologist and palliative care physician with CancerCare Manitoba and an assistant professor at the University of Manitoba. He accompanied Hughes as a guide on one of her psilocybin trips.

In his 35 years as an oncologist, he’s witnessed thousands of cancer deaths and says at least half of patients have great difficulty accepting that they will die. He, too, is frustrated by Health Canada’s reluctance to make psilocybin more readily available for medical purposes. “The bureaucrats are looking at safety issues, but a lot of those concerns have already been disproven in the research.” He says that many people still have the “just say no to drugs” mindset. “It’s a very similar situation to what happened with cannabis. It took Health Canada 30 years to approve it, and now it brings relief to so many.”

He hesitates when asked if he’s tried psilocybin himself, initially asking to go off the record, but then agreeing to go public. “Yes, and I was totally blown away. I never did drugs in my life. It was amazing. Very spiritual and mystical and, I would say, life-changing.”

Daeninck explains that he’d bottled up his emotions around a difficult incident in his life, buried it in a metaphorical “black box” that was opened during his trip. “The experience was very spiritual — I was flying through lovely cathedrals, and there was a real sense of wonder. And then I went into a dark time, and there was the black box.” He’s since made steps to resolve that issue and says he’s happier than he’s ever been.

Dr. Houman Farzin, a palliative care physician at Montreal’s Jewish General Hospital, has supervised or attended psilocybin-therapy assisted sessions with five patients, including Quebec’s first legal and publicly funded psilocybin group session for two cancer patients. He says he has witnessed similar life-changing experiences among his patients.

“Often what happens is that we suppress content in our subconscious, especially when we are vulnerable at a young age. Our mind pushes things deep into our psyche — the content is there, but we don’t have access to it,” he explains. “As we enter the end of life, it comes bubbling up, and we try to suppress it.”

With psilocybin, Farzin continues, “we can unlock the gates and allow patients to face the things they are resisting. It’s like a pressure valve being released. Patients become calmer and at ease — there is an acceptance. By unlocking the gates, we facilitate wholeness.”

It’s different from a drug like morphine, which reduces physical pain but doesn’t alleviate “psycho-spiritual pain,” he says. Psilocybin allows people to detach themselves from their experience of pain and suffering and “enter a realm that is beyond an ordinary state of consciousness. They are able to create meaning and experience transcendence — something greater than themselves, something endlessly beautiful, something unifying.”

Magic mushrooms sound like they could be a magic bullet, but psilocybin does have its risks. It’s not recommended for people who have a personal or family history of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder because that can elevate the risks of side effects or adverse events. Those with cardiac conditions are also at risk since psilocybin can raise blood pressure and heart rate. And there’s always the chance of a bad trip with frightening hallucinations and paranoid thoughts.

This underscores the importance of taking psilocybin under expert guidance by trained professionals. Its effects can be highly variable and depend largely on the mindset of the user and the environment in which they have the experience, factors commonly referred to as “set and setting.”

Canada wasn’t always wary of psychedelics as medical treatment. In the 1950s and ’60s, it was a hotbed of research and activity. The Hollywood Hospital in British Columbia, which attracted a high-profile clientele including singer Andy Williams and actor Cary Grant, was home to this country’s first psychedelic treatment program for mental health issues. Saskatchewan’s Weyburn Mental Hospital also offered psychedelics. It was run by the English psychiatrist Humphry Osmond, who coined the word “psychedelic” in 1957 and famously introduced psychedelics to Aldous Huxley, author of the dystopian novel Brave New World.

But when widespread recreational use of drugs, including psychedelics, became available to the “turn on, tune in, drop out” anti-establishment generation, U.S. President Richard Nixon called a halt. He declared a war on drugs in 1971, labelling them “public enemy number one.” The move three years earlier by his predecessor Lyndon B. Johnson to make them illegal also contributed to the shutdown of research for decades, both in Canada and in the United States.

Now, as the mental health crisis among North Americans intensifies, psychedelics could represent a new frontier of treatment. Only about four in 10 patients respond fully to first-line anti-depressants, and 30 percent of cases of major depression don’t respond to mainstream treatments at all. Talk therapy can take many sessions and is too costly for many.

“Hallucinogenic drugs may very well turn out to be the next big thing to improve clinical care of major mental health conditions,” says Danilo Bzdok, lead author of the world’s largest study on psychedelics and the brain. It was conducted by a team of researchers that included scientists from the Montreal Neurological Institute-Hospital and McGill University’s department of biomedical engineering, among other institutions.

Bruce Sanguin is a former United Church minister of 30 years who now provides harm-reduction psychedelic-assisted therapy as a psychotherapist in Calgary. His patients bring the substances, including psilocybin, and he assists on their trips. In his newest book, Dismantled: How Love and Psychedelics Broke a Clergyman Apart and Put Him Back Together, he writes about how his psychedelic experiences helped him heal from trauma and open his heart.

Sanguin believes psychedelics could have far more widespread transformative effects, including for religious institutions. “If the church wants to survive, it should be advocating for the legalization of psychedelics,” he says. “Seminaries should be initiatory schools for future guides/ministers.”

Spencer Hawkswell, president and chief executive of TheraPsil, the non-profit coalition that advocates for legal access to psilocybin therapy for Canadians in medical need, agrees that the benefits to society could be even more revolutionary than treating mental health issues. His personal psilocybin trips proved to him that the substance can spark profound spiritual experiences.

“They taught me that there has got to be meaning in the world. There is a God-shaped hole in people’s hearts, and psychedelics do a good job of making people realize that there is more to life than their career, their iPhone, drinking and eating,” he says. “It tells them there is a purpose to be discovered. Psilocybin brings the most amazing changes to people’s lives.”

Some small-scale studies bear this out. When taken for spiritual purposes, psychoactive substances such as psilocybin are considered entheogens, from the Greek meaning “capable of generating the divine.” In 2006, for example, a team at Johns Hopkins University published results of a study that showed doses of psilocybin led to “mystical-like experiences” that the majority of participants rated as among the most powerful spiritual experience of their lives.

Evidence based on prehistoric paintings in North Africa suggests that humans may have used psilocybin thousands of years ago. The Aztecs referred to the sacred mushroom as “teonanácatl,” meaning “god’s flesh.”

Huxley, the British novelist, was one of the first people in western culture to predict that psychedelics would become part of religion in the future. He had an epiphany in 1953 after he tried mescaline.

“These new mind changers will tend in the long run to deepen the spiritual life of the communities in which they are available. That famous ‘revival of religion,’ about which so many people have been talking for so long, will not come about as the result of evangelistic mass meetings or the television appearances of photogenic clergymen,” he wrote. “It will come about as the result of biochemical discoveries that will make it possible for large numbers of men and women to achieve a radical self-transcendence and a deeper understanding of the nature of things.

Plenty of religious organizations are running with the idea. Harvard Divinity School, for example, is part of a new $16-million interdisciplinary program dedicated to the study of psychedelics. Some 150 spiritual care professionals, researchers and educators are members of the Chicago-based Transforming Chaplaincy Psychedelic Care Network, which supports psychedelic-assisted therapy.

Shefa in Berkeley, Calif., advocates for a religiously inclusive approach to Jewish experience in the psychedelic world. The Divine Assembly in Salt Lake City, Utah (founded by a former Mormon Republican state senator), Psanctuary in Louisville, Ky., and Zide Door and Sacred Garden Community in California are using psilocybin as a tool for spiritual enlightenment.

And then there’s Ligare: A Christian Psychedelic Society. It is a network of clergy and others dedicated to making “direct experience of the sacred available to all who desire it through the responsible legal use of psychedelic medicine and within the context of the Christian contemplative tradition.”

Hunt Priest, an Episcopal priest based in Savannah, Ga., founded the group after he participated in a 2016 Johns Hopkins University study to determine the effect of psilocybin on the religious experience of two dozen faith leaders.

“Christianity has developed ways of bringing about non-ordinary states of consciousness: fasting, meditation, prayer retreats. So religions already have systems in place for preparing people for and making meaning of mystical experiences,” he said in an interview with The Microdose, a newsletter supported by the UC Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics.

If psilocybin becomes legal, members of Ligare want to offer the substance to parishioners at Christian retreats.

“We’d do all the things you’d typically do on a Christian retreat, but midway through, participants would have a psilocybin experience,” Priest said. “That way they’d have a few days to build community, have that experience, then make sense and make meaning out of it.”

At press time, Hughes was three months beyond the survival date her doctors had anticipated. She says she will use whatever time she has left to advocate for the expanded use of psilocybin by giving media interviews like this one and lobbying government officials. With her fear of death drastically diminished, she says the only anxiety she now feels is the urgency to “get things done” before she dies. Recalling her last psilocybin trip, she talks about floating out in space with a feeling “beyond contentment, a melting away of the self” and “a feeling of intense love and compassion for everything.” She continues: “I kept saying, ‘I want to live here; I want to live here.’ I think I will go back to that place certainly on my exit. My belief is that my consciousnesses will dissipate into a unified consciousness. I, myself, will not continue to exist, but it’s enough for me to have at least some kind of existence. What I feared was obliteration.”

***

Anne Bokma is a journalist, author, speaker, writing coach and workshop leader in Hamilton.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s June 2024 issue with the title “Facing Death with Magic Mushrooms.”

These mushrooms really opened my mind, worked on my anxiety and depression after I got some from Alpha_Fungi on Instagram, I think we should try these natural remedies💚💚