One morning three years ago, while riding a packed commuter train, I was struck by one of those thoughts that’s obvious and not obvious at the same time, like when you’re going about your day and suddenly realize you’re standing on a planet that’s spiralling through the universe.

The thought was this: every single person on that train was born to a woman — a woman who had first become pregnant.

As I looked from person to person, I imagined their mothers: some young, some older; some in Canada, others in faraway countries; some elated, some devastated. Each one experiencing a tiny surprise that changed the course of her life.

I held this thought as I made my way through the throngs of commuters at Toronto’s Union Station.

So many people; so many pregnant women. So many generations of mothers, stretching back hundreds of thousands of years, in order for all these people to be coming and going in their busy days.

My thoughts, as they often did at the time, quickly took a dark turn: Why was motherhood — this seemingly normal part of life — beyond my reach? Why did I feel so alienated from the flourishing of humanity? Why couldn’t I have a child too?

It feels a bit like cheating to share this story, now that I know it has a happy ending. I can be brave about it because I got lucky — if you can define luck as reproductive science, persistence, a marriage strong enough (sometimes just barely) to withstand the emotional toll, salaries able to finance the $28,000 in procedures, and medical insurance able to absorb another $14,800 in drugs.

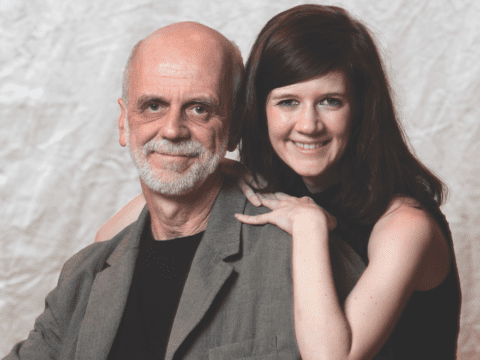

My husband, Jamie, and I started trying for a pregnancy within the first year of our marriage. I was 32; he was 36. We were two people living in a four-bedroom house with three bathrooms on a quiet cul-de-sac. We had stable incomes, six years of child-free relationship behind us and a girl’s name we both liked. We had friends and siblings with kids, and excelled at playing Auntie and Uncle. We’d always assumed that we’d eventually have our own baby, pitter-pattering around the kitchen, riding in the backseat of our car, playing outside in the yard. Eventually had arrived.

For eight months, we tried to conceive. Nothing. We went to our family doctor. She offered me drugs and a referral to a specialist. She used the word “infertile” and told us to decide how much we’d be willing to do and spend to have a baby. I was stunned. Infertile?

Infertility, usually defined as the inability to conceive within 12 months, affects one in six Canadian couples, according to Statistics Canada. But it’s surprising how few people talk about it or how seldom it’s discussed in the media. Infertile couples — when they do surface — most often appear in storylines about adoption. In these narratives, the birth mother and her baby are the protagonists. The adoptive parents are mere extras morphing from the shadows with no history of their own, signing some papers and leaving with a newborn.

But infertile women and men do have a story to tell, one that’s important to share in our baby-obsessed culture. And it doesn’t always have a happy ending.

***

The journey through infertility is equal parts medical and emotional.

On the medical side, my story began with a series of tests for both Jamie and me. The maddening diagnosis: unexplained infertility. The specialist recommended a course of action that began with intrauterine insemination (IUI). We tried it six times at $350 per attempt. No luck.

Losing faith in western remedies, we tried Chinese medicine. Looking over my basal temperature charts, the Chinese medicine doctor determined I was cold; the treatment he prescribed would improve my qi. For six months (and at a cost of about $1,500), I drank a foul-tasting tea, swallowed tiny red pills made with ground deer antlers and paid regular visits to his eucalyptus-scented office for acupuncture. Still no luck.

Returning to western medicine, we switched specialists, tried IUI two more times and then turned to the much pricier in vitro fertilization (IVF). I’ll come back to that later.

On the other side of the story is the emotional turbulence that shook me to my core. I’d pin all my hopes on each new treatment. (“I have a good feeling this time!”) I’d project an image of myself in the future, pregnant, and telling friends and family the story. (“It all worked when we finally did this.”) Then the bad news would come, and I’d crash.

In the beginning, my plan was to get this little blip on the road to parenthood taken care of quietly and privately. My need for secrecy was closely linked to my feelings of failure about being unable to procreate, bearing the weight of the label “infertile.” The first specialist’s office was in a building associated with McMaster University Medical Centre in Hamilton. Several medical practitioners operated out of the same space; the waiting areas were all in an open-concept atrium. On one visit, I saw my uncle in another waiting area and ducked to avoid him — twice. What if he knew? What if he told my family?

On the other hand, what if people didn’t know? With the years of marriage racking up, I felt like a walking question mark. Why weren’t we starting a family? If they didn’t ask outright (which they often did), they must be wondering. I worried that people would assume I didn’t like kids, that I was too engrossed in my career or too self-interested to reproduce. Did my mother-in-law think it was my fault?

Each failed attempt made me feel worse about myself and made the need to have a child more urgent. In time, a baby wasn’t even the goal anymore. It was just the pregnancy I was after. I’d think: I’d take a miscarriage, just to know that pregnancy was possible.

I wish I could tell you that I faced adversity with a brave smile, that I refused to let fear, anger and self-pity get a foothold. Instead, I felt more like a person under a dark spell — like Gollum in The Lord of the Rings, craving and despising that one precious thing, losing myself in order to find it.

I coped by avoiding. I stopped going to baby showers. I stopped holding babies. I stopped looking at babies passing in strollers. I stopped watching TV diaper commercials and shows where anyone was having a baby. I stopped going to any sort of gathering where someone might ask if I had or wanted kids.

I stopped feeling happy for people who became pregnant. When my older brother e-mailed to say his wife was pregnant with their second child, I burst into tears — first of sadness, then of shame. I had hoped to be the next person in our family to make an announcement.

I also stopped going to church. Other reasons compounded my decision. But as a 30-something in an aging congregation, I knew others often assumed I had come because I had kids to put in Sunday school. Christmas is unbearable when you’re struggling with infertility, and Christmas at church is worse. Did I want to hear about a virgin with child — pregnant without so much as breaking a sweat? Did I want to sing songs and hear stories about a newborn baby? Not on your life.

If I strayed from avoidance, I paid a price. Holding someone else’s infant for even a moment meant I’d be alone and crying in the bathroom the next.

I began to think of myself as an “underdeveloped woman,” like a tween girl wondering when she’ll hit puberty like the rest of the gals. I couldn’t break into that club of women who define their femininity by their power to create, to endure the throes of childbirth, to nurture. The negativity had accumulated to the point where, as much as I wanted a baby of my own, the mere mention of them had become intolerable.

At times, Jamie and I were able to laugh about it. Standing in our garden one fall, he cuddled a pair of butternut squashes in his arms like a pair of jaundiced twins. (“At least we can grow something!”). But on the whole, our marriage suffered. Sex became perfunctory. My need to talk about infertility incessantly butted heads with Jamie’s need to please just give it a rest.

With more to express than Jamie was able to absorb, I relied on others to soak up the overflow. Even as I grew weary of my own voice, friends and family members gave me their time, their encouragement, their hugs — even their bodies. My sister offered me her eggs; a friend offered to be a surrogate. I was overwhelmed by their generosity and terrified that I might have to accept.

I went to a group therapy session where I met two other couples. The first pair were new to infertility. The second pair were at the end of their rope, having spent a fortune on every option imaginable. The wife wept while the husband tried to placate: “Everything happens for a reason.”

Determined to manage my emotional health, I booked several one-on-one sessions with a counsellor. She taught me deep-breathing techniques, and we did visualization exercises that involved welcoming the goddess into my womb. She helped me see that my life wasn’t defined by infertility.

But she didn’t help me answer the questions that dogged me: If I can’t have children, how do I let that go? How do I live a meaningful life? How can I stop feeling like my entire adulthood will be one long blur of work and leisure, with no discernable change until I retire? Even then, what would I do while my friends were grandparenting? Exactly what I was doing now — filling time. Theoretically, I knew it was possible to find a meaningful life without children. It just seemed impossible for me.

There was one space where I felt it didn’t matter whether or not I was a mom: work. I didn’t tell anyone at the office what I was going through (except my supervisor, who graciously gave me all the time off I needed for medical appointments). No doubt my co-workers would have been sensitive and supportive. But I needed a bubble where I could talk about other things, think about other things. At work, I felt whole.

***

Life carried on in this way for about three years: good days at the office, bad days at home. Then, in the lead-up to what would have been our ninth IUI, my body overreacted to the hormones, stimulating too many eggs all at once. With artificial insemination, the risk of multiple births was too great. But if we wanted to retrieve the eggs and take our treatment to the next level, we could. This was our gateway to in vitro fertilization.

IVF, which produced its first baby in the United Kingdom in 1978, involves removing eggs and mixing them with sperm in an incubator for three to five days. Once fertilized, the embryo or embryos (usually no more than two) are transferred back into the woman’s uterus. Everyone crosses their fingers that at least one embryo will implant itself into the lining and grow into a baby.

For two months prior to the egg retrieval, I injected myself with hormones daily — a needle into the fat of my stomach or thighs — to stimulate the release of lots of eggs. My body primed, we drove to a clinic in Mississauga, Ont., where the doctor removed my eggs. The process involves inserting a needle into the body, through the vaginal wall and into the ovaries. Even with light sedation and local anesthetic, it hurts. In 2010, doctors in Canada performed 11,806 in vitro fertilization treatments resulting in 3,660 live births, according to the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society.

IVF is expensive, about $7,500 per try. Seven years ago, an expert panel appointed by the Ontario government recommended that the provincial health plan cover fertility treatments. When couples pay their own way, the panel argued, they typically transfer two and occasionally three embryos to minimize the cost while increasing the odds that at least one baby will result. But this practice raises the possibility of multiple births, which carry a higher risk of miscarriage, premature birth and mental and physical disabilities. Single-embryo IVFs are less risky and could save the health-care system hundreds of millions of dollars over the long term. The Ontario government shelved the study, people protested at Queen’s Park and nothing changed.

In 2010, the Quebec government became the first province in Canada to fund up to three rounds of single-embryo treatments. The program has yet to be analyzed — no formal study of its cost-effectiveness exists, and some reports suggest it is much more expensive than the province originally anticipated. Yet politicians, including Yves Bolduc, the former Quebec minister of Health and Social Services, have freely cited two statistics: that as a result of the program, the incidence of twins conceived through IVF decreased from about 30 percent to well under 10 percent; and that the province has saved between $30 million and $60 million per year in health costs associated with risky pregnancies and problem births.

The debate surrounding publicly funded IVF drew the usual outpouring of nastiness from online commenters. And actually, I don’t disagree with all of it. Children are indeed a gift and not a right. The world is overpopulated, and adoption is an ethical alternative (arguably no one should have kids until every last child is adopted). Money could well be spent on more pressing health-care needs.

The online commenters are also correct in their charge that many women facing infertility have waited too long to start trying to conceive naturally. A woman’s fertility peaks sometime in her mid- to late-20s. But the average Canadian woman delays having her first baby until age 29. More than a third of first-time moms are in their 30s. Eleven percent are 35 or older.

What’s going on? Simply put, human biology is at odds with feminism. We encourage young women to get an education, establish a career, be financially independent and wait for Mr. (or Ms.) Right rather than settling for Mr. (or Ms.) Right Now. We tell them to do all of this before bringing kids into the picture.

So yes, I do think taxpayers should fund IVF, especially for those who can’t afford it. It’s about more than minimizing risky pregnancies and controlling health-care costs. If we want a society where women are equal and mothers are educated, financially secure and in stable partnerships, then we have to accept that they’re going to delay starting a family. It’s not our fault our ovaries didn’t read The Feminine Mystique.

***

As we prepared for our first IVF procedure, we were cautiously hopeful. This was the big leagues, with the price tag to match. Because I was over 35 but under 40, my chances were about 31 percent for pregnancy and 26 percent for live birth, according to the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society. So maybe, just maybe.

But when our first IVF failed to even produce an embryo, my husband and I were shocked. As our specialist, Dr. Richard Stopps, explained, either the membranes of my eggs are too hard or my husband’s sperm lack the chompers (okay, he said “enzymes”) to break through — or a bit of both.

Strangely, there was a silver lining: we weren’t to blame. If our sperm and eggs wouldn’t fertilize, even bumping up against each other in a temperature-controlled incubator, then there was nothing I could do to change it. This was significant. When infertility is unexplained, well-meaning people dish out all kinds of advice, chiefly, “Just relax and have fun!” On one level, I rejected that kind of thinking, but on another level I absorbed it — and projected it onto every decision I’d ever made: Is it what I eat or don’t eat? Drink? Is it Teflon pans, deodorant, hormones in chicken? Should I do more yoga? Be more welcoming of the goddess? Is God or the universe telling me that I won’t make a good parent? Am I too uptight?

Our second IVF was paired with an additional treatment called intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), a 20-year-old procedure where they not only mix the sperm and eggs outside the body, but also force a single sperm into each egg with a needle.

In the lead-up, the drugs that induce extra eggs once again caused my body to hyperstimulate, releasing 37 eggs in a single month, more than my doctor had ever seen. From those eggs, the embryologist selected 16 of the best to fertilize. I was ready to go, but Dr. Stopps advised caution: instead of incubating the embryos for three days, we’d wait five days, giving my body time to settle down. Ovarian hyperstimulation, especially coupled with the hormone jolt that comes with pregnancy, can hospitalize a woman for weeks. In extreme cases, women have died.

In those five days, all 16 embryos crashed before they could be transferred, save one. Back at the clinic, I watched on the bedside ultrasound monitor as a fuzzy white blob — a single living embryo, cells dividing, surrounded by fluid — popped out of a tube and floated into my uterus. For the very first time in this long journey, there it was — the start of life. Two weeks later, we learned it hadn’t implanted.

Soon after, I went to a yoga class. As I lay on my back in the restful pose, shavasana, a thought came to mind: “I forgive my body. I forgive it for failing me.” Hot tears welled up in my eyes. I snuck out of class early and wept all the way home.

***

My husband and I agreed that our third IVF attempt would be the last. It was getting too expensive, and our insurance company had sent us a letter saying we were reaching our limit for the drugs. Also, we couldn’t take much more. The question loomed: if it doesn’t work, then what?

I know the answer seems obvious. Why not just adopt? People always ask the question in that way — “just adopt” — like all you have to do is drop in to your neighbourhood orphanage and pick out a cute one. As anyone who’s looked into adoption can tell you, the process can take years, cost thousands and incur its own emotional toll. It often means children with special needs, older children or children from other countries. It’s open relationships with birth mothers — or children whose medical history is unknown. It’s wrestling with ethical questions like whether the developing-world birth mother might have kept her child had she been more affluent, and should we adopt from those countries or try to financially support poor mothers?

Despite the risks, moral quandaries and challenges, if our third IVF failed, I was ready to adopt. But Jamie, in his gut, didn’t believe he could truly love a child who wasn’t his own. I tried to convince him otherwise. Then, I dragged him to an expensive psychotherapist, believing we would get to the bottom of his hang-ups and set him straight. In three sessions, the tables turned. I finally heard him say no. I had to accept his limits. If I wanted to adopt, we’d have to separate. What choice would I make? Would I rather be a single mom with an adopted child? Or stay married to my partner of 10 years?

I genuinely tried to envision a meaningful life without children. I would become a radical environmental activist. I’d move to New York City. I’d travel. I’d throw myself into my career and work my way to the top of a major magazine. I’d move to Africa and work for a good cause.

Was there a niche in this world where few people would have children, want them or even talk about them? I could imagine only one: the adult film industry. Unfortunately, I’m woefully underqualified.

In the end, I was spared having to answer the big questions. For our third IVF, we adjusted my medication to avoid hyperstimulation and produced four good embryos. Two were cryopreserved for future use. The other two were transferred — and just like that, it worked. I was pregnant.

At first, I was afraid to be happy, certain that a miscarriage was pending. But as the weeks passed, gratitude replaced fear. I was thankful for morning sickness, for my aching, cumbersome body: this was for real.

Four years and nine months from the beginning of our journey, we welcomed a six pound, 10 ounce baby boy into the world. His name is Chase.

***

At a recent retirement party for one of the nurse practitioners at his Hamilton office, Dr. Stopps — who has worked with thousands of prospective parents over the past 38 years and knows pretty much everything there is to know about infertility — admitted to me that the one thing he doesn’t understand is the persistence. Why do people keep trying? Why do they put themselves through so much?

My answer: It’s more than wanting a baby. It’s wanting to fit in, wanting to graduate through the stages of life, wanting to fulfil the dreams of marriage and family, wanting some piece of yourself to remain after your death. It’s also about being caught up in the medical regimen — remembering to take your medication, give yourself an injection, drink your tea, chart your temperature, make an appointment. It’s the buildup, the effort, the letdown. It’s the biological time bomb ticking away, threatening to blow up the entire plan, hammering its steely message into your head: you can’t, you can’t, you can’t. It’s holding on to the hope that maybe if you persist, maybe you still can.

The stigma of infertility is still with me. I am haunted by what would have happened if our third IVF had failed. And although we have a baby, as a couple, we are still infertile. But I think the experience has also deepened my compassion for others who feel isolated, set apart from the course of “normal” life, unsure how to get back on track. Divorce, illness, depression, addiction, death of a loved one — infertility is a snap compared to some of these challenges. But in my own way, now I get it.

***

When Chase was about a year-and-a-half old, we unthawed those last two embryos and transferred them. Drugs helped optimize the chances of implantation. Acupuncture increased blood flow to my uterus. I cut back on caffeine and cut out alcohol in the lead-up to the transfer, just in case. We let ourselves imagine another pregnancy, another birth, another little baby to hold and to love, a sibling for Chase, a second miracle. On a Friday afternoon, two weeks after the transfer, our doctor’s office called with the results of a pregnancy test: negative.

That night, after Chase went to bed, we poured a couple of beers and lit four candles — one for each of the transferred embryos that didn’t take, honouring them as tiny beloved souls who might have been. We talked, cried and agreed that this journey that had defined most of our married life had finally come to an end. It hurt that there wouldn’t be a second baby. But unlike the previous failed attempts, we could envision our future. We would be a one-kid family. And we would be happy.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s January 2014 issue with the title “Four years, 9 months.”