Last December, leaders of Toronto’s Jewish community donned their dinner jackets and evening gowns and made their way to the Jewish National Fund’s 65th annual Negev Dinner at the Metro Toronto Convention Centre. The mood was upbeat: the fundraising target had easily been reached, and the evening’s guest of honour would be no less than the prime minister of Canada, Stephen Harper.

From the sidelines I watched as the 4,000 invited guests took their seats, some greeting friends and acquaintances in the crowd. Soon all attention focused on centre stage, where the master of ceremonies was calling the evening to order.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

But I found myself distracted by peripheral noises from far outside the room. What I heard was a strange, tinny chant: “Viva, Viva Palestina! Viva, Viva Palestina!”

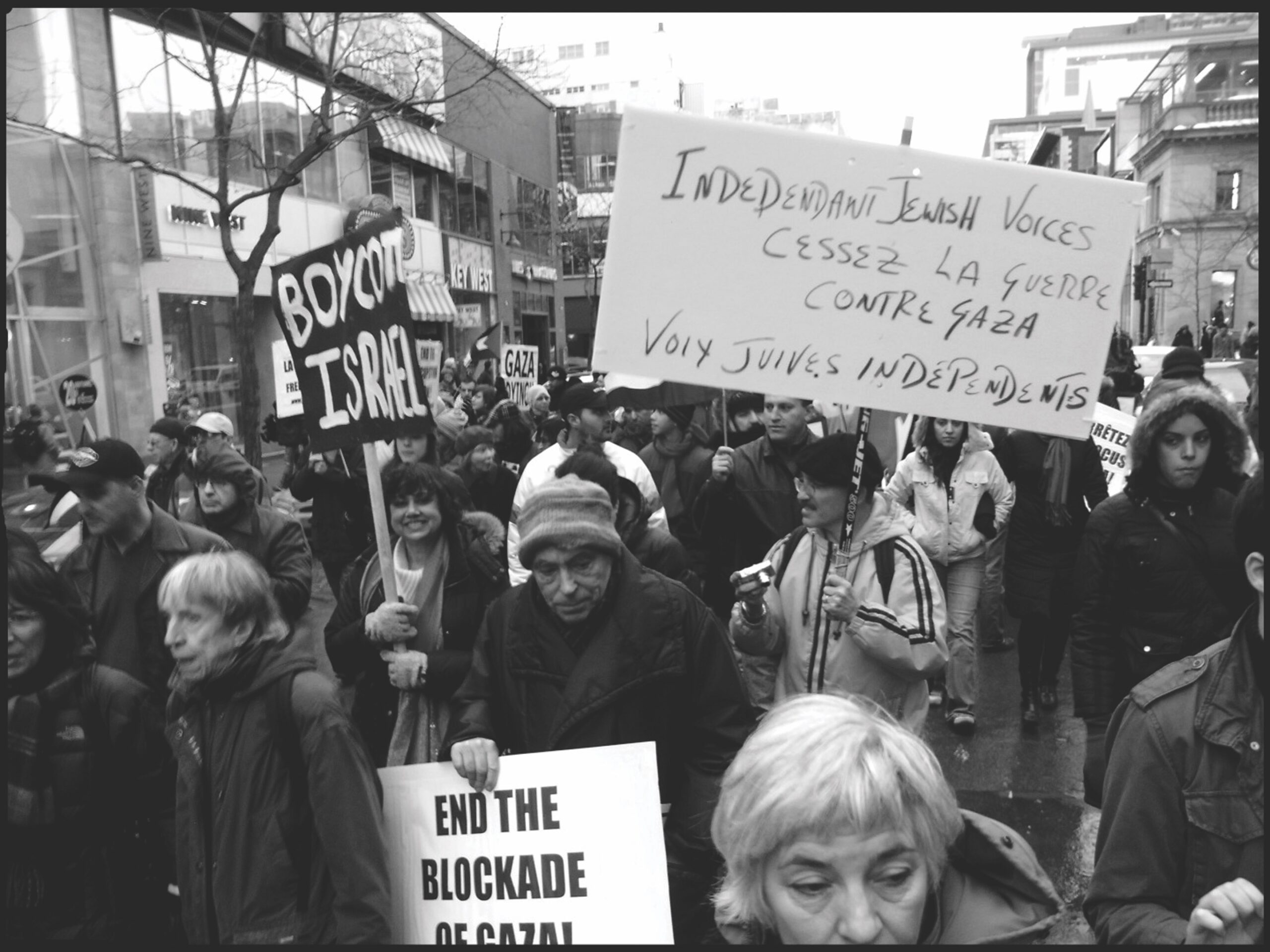

Leaving the hall, I found a crowd of a hundred or so people not far from the convention centre carrying signs that screamed, “Stop the illegal blockade of Gaza,” “End Israeli apartheid,” “Treaty rights not greedy whites!” First Nations drummers set the beat. A young man on a makeshift stage was chanting, “Harper, Harper, you will see. Palestine will be free!” Then the drums stopped and University of Toronto sociologist Sheryl Nestel, a short-haired, bespectacled woman in her early 60s, took the microphone. She is on the steering committee of Independent Jewish Voices (IJV) Canada, which organized this rally.

“I am so glad to be among those who have come together to protest against the travesty committed by the Jewish National Fund in honouring Stephen Harper,” Nestel said. “By supporting the Jewish National Fund, those attending this event lend moral and financial support to the ethnic cleansing of Palestine, the use of collective punishment, the confiscation of lands, the destruction of homes and communities, and the erasure of evidence that scores of Israeli parks, schools and homes are built on stolen land where Palestinian communities once flourished.”

She continued, “I’m here representing Independent Jewish Voices, a national organization working to encourage members of the Canadian Jewish community and others to speak out about the violations of human rights perpetrated by Israel against the Palestinian people.”

The growing stature of Independent Jewish Voices among Canadian individuals and organizations opposed to Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and blockade of Gaza belies its small membership, at last count about 350. While IJV Canada has no standing with The United Church of Canada or any other mainline Canadian denomination, it finds common cause with groups within the church such as the United Network for Justice and Peace in Palestine and Israel. IJV made its presence felt before, during and after the United Church’s last General Council in 2012, when commissioners approved a limited boycott of products produced by Israeli companies in the West Bank. And the group will no doubt be a presence again when the General Council reconvenes in Corner Brook, N.L., next summer.

Who, and what, exactly, is IJV?

Of the three letters that constitute the acronym IJV, the most important is the “I” — Independent. On any given issue, the range of positions and nuances among the IJV Canada membership is perhaps greater than the number of actual paid-up members. Tyler Levitan, IJV’s sole paid employee, tells me that IJV Canada, which was formed in 2008 and is not formally linked to IJV branches in the United Kingdom and Australia, welcomes people with different points of view, asking “only that they hold on to our core principles: an end to Israeli occupation of Arab lands occupied in 1967; equality for all citizens in one state or two; acknowledgment of Palestinian right of return.”

Unlike other progressive Jewish organizations such as J Street and the New Israel Fund, IJV Canada supports the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement, which calls for an economic, cultural and academic boycott of Israel. However, IJV has focused its recent energies on a targeted boycott of products made in the West Bank — a position similar to the one the United Church eventually took in 2012. Church officials maintain the General Council action was not shaped or influenced by IJV.

+++

I first met Sheryl Baron in Israel in 1974. At the time she was living on Kibbutz Gezer and dating Sydney Nestel, a good friend from my youth in Toronto. Soon Sheryl and Syd married, moved away from the kibbutz to a nearby town, had three children and tried desperately to make ends meet.

Sheryl was born to a Jewish family in Los Angeles. She had moved to Israel to get away from Richard Nixon’s America, which was still dropping napalm in Indochina. She believed that Israel represented a unique opportunity to create a social, political and economic utopia that could someday stand as a “light unto the nations.” She also fervently believed that Israel was a project of the Jewish people, for the Jewish people, by the Jewish people.

Their dream soon faded. What the Nestels experienced, and how they interpreted their experience, is recounted in a thousand books about the origins of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and in another thousand books about the painful transition from Israeli socialism to a free and rather unforgiving market economy.

The Nestels did not roll over and play dead. They resisted in every way they could. One story of their resistance has stuck in my mind over the years. It tells of the kind of morality that is common to many members of IJV.

With the 1967 and Yom Kippur wars still fresh in their minds, Israelis in the mid-1970s were learning to cope with an overabundance of intelligence information gathered by Israeli agencies.

Much of the time it was a false alarm, but sometimes it wasn’t. Israeli homeland security would react by setting up makeshift checkpoints guarded by soldiers or police. Standard procedure was to wave through Israeli drivers and force Arab-Israeli vehicles to queue up in impossibly long lines and subject them to full and often humiliating searches. The Nestels refused the privilege, opting instead to show solidarity with Arab Israelis by voluntarily queuing up behind them.

Such solidarity remains a seminal part of Sheryl Nestel’s life. It is also one of IJV’s two central pillars. The other pillar is education, which to me sometimes seems less interested in moral conversation than in implementing an intense program of deprogramming. This came through clearly in Nestel’s speech to the demonstrators protesting the Negev Dinner in Toronto last December.

“Independent Jewish Voices sees Jewish support for the Palestinian struggle as a moral and strategic imperative which is based in historic Jewish values of social justice,” she declared. “We aim to create a rift in the Jewish community over the deal with the devil in which support for Israel is traded for Jewish loyalty to a neoliberal government hell-bent on expanding racism, environmental exploitation, militarization and economic injustice.”

It’s worth noting that IJV is virtually unheard of in Israel, where progressive groups such as B’Tselem are well established and have a significant public profile. In Canada, the members of IJV are reviled as self-haters and far-left ideologues by the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs (CIJA), the umbrella group that has spoken for Canada’s 330,000 Jews since the demise of the Canadian Jewish Congress in 2011.

While the Canadian Jewish Congress and The United Church of Canada may have had their differences, they continued talking to each other up until the CJC ceased to exist. In reaction to the United Church’s 2012 boycott decision, CIJA refuses to have anything to do with the United Church or any organization in which the United Church is involved, chief among them the Canadian Christian-Jewish Consultation.

It’s a mistake, however, to assume that the church and IJV could drift into even a quasi-formal relationship. Rev. Bruce Gregersen, who until his recent retirement was the United Church’s senior program officer, told me that the General Council’s adoption of a targeted economic boycott in 2012 was based on the eyewitness testimony of church members who have lived and worked in the occupied territories, as well as input from church partners in the region. “In point of fact, the IJV’s position, which was heard at our convention, was very far from the deciding factor,” said Gregersen.

I wondered aloud whether a factor that wasn’t discussed very openly in 2012 might have been a sense of urgency over the growing political influence of the Canadian Christian Zionist movement, whose most extreme members hold that the Second Coming will only be possible when all Jews return to a Holy Land that includes all the real estate named in the Bible. The otherwise even-keeled, soft-spoken, infinitely generous Gregersen seemed to lose his reserve, calling the Christian Zionist movement “heretical” but not elaborating.

However it originated, the limited boycott espoused by the United Church is carefully nuanced, moderate and reasonable compared to some of the more sweeping sanctions being instituted by other organizations, especially in Europe. But as moderate as the United Church’s stand may be, it is not sufficiently value-neutral to ward off recriminations by some Canadian law firms that have gone on the record arguing that the church has no business meddling in the affairs of Israel. One firm, whose correspondence Gregersen showed me, went so far as to argue that the occupation is not illegal but rather a “territory in dispute.”

This kind of attitude infuriates Sheryl Nestel. “When a politics of dispossession and racism against Palestinians is pursued in the name of protecting and defending the Jewish people, we need to say loudly that such politics reek of hypocrisy and all of us, Jew and non-Jew, should be able to name that truth without fear of recrimination,” she told the demonstration outside the Negev Dinner in Toronto last year. Nestel then thanked the audience cordially and left the stage.

Back at the convention hall, Stephen Harper led a dance band through a remarkably off-key set of rock ’n’ roll standards and praised Israel as a “light of freedom and democracy in what is otherwise a region of darkness,” drawing a thunderous ovation that completely overwhelmed the faint sound of the drumming outside.

David Berlin is the founding editor of the Walrus magazine and author of The Moral Lives of Israelis: Reinventing the Dream State. He divides his time between Toronto and Tel Aviv.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s July/August 2014 issue with the title “The dissenters.”