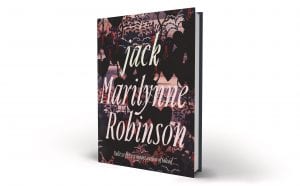

I have always loved Jack, the eponymous anti-hero of Marilynne Robinson’s new novel. He loiters in the pages of her previous three novels, world-weary, self-deprecating, apologetic and charming. His transgressions are discussed by others. He is tragic and contradictory, an atheist who believes in predestination, a minister’s son who lies and steals.

Gilead, Home and Lila, the other novels in the series, all take place in the fictional town of Gilead, Iowa. Each book revisits the same events from a different character’s point of view. Each records the prodigal son’s return: Jack comes home to visit his dying father 20 years after fleeing a scandal. His original sin, we learn, was fathering a child with a girl from an impoverished family, then absconding. Near the end of Gilead, Jack discloses another secret. He is married to a Black woman, and they have a child. It’s 1956; interracial unions are illegal in 26 American states. Jack fears the news will kill his frail father.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Gilead won the Pulitzer Prize in 2005. I read it a few years later while I was in the midst of losing my faith. Gilead is written in the wistfully luminous voice of Rev. John Ames, an aging Congregationalist minister and the best friend of Jack’s father. The book caught me in the throat. The plot is slight: the old man sits in his study and reflects with relentless gratitude on his life. Yet each scene is lit by a cosmic radiance, like a light-pierced Rembrandt painting. Water spills off a man’s moustache “like rain off a roof”; the sun and moon stand simultaneously on opposite horizons with “great taut skeins of light suspended between them”; a child baptizes a kitten and feels its mysterious life mingle with his own. Strange, perhaps, that an unabashedly theological novel would accompany me on my journey out of Christianity. But I was hungry for a vision of the world that honoured the intensity of my childhood faith without walling it in. Robinson’s Christianity shed light on the mystery of existence without trying to stake too large a claim. From the very beginning, I felt an affinity with the wayward Jack. A dozen years later, I was eager to hear his story.

More on Broadview:

- Jael Richardson on truly diversifying publishing

- Two Canadian films you won’t want to miss

- When I lost my belief in hell, my faith began to unravel

Jack is a love story set in segregated St. Louis in the late 1940s. The novel opens with Jack and Della talking in a graveyard. Jack lurks in a tombstone’s shadow while Della stands under a street lamp. The lighting is significant: Jack is an unemployed alcoholic recently released from jail, the “Prince of Darkness,” as he half-jokingly calls himself; Della is a bright young teacher at the first Black high school west of the Mississippi River and the daughter of a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. They talk of poetry and metaphysics while enacting the tentative dance of trust between people newly in love.

As their relationship develops, the forces arrayed against it come into focus. Della risks losing her job, her honour, her family, even her freedom. Marriage would be a felony. Della’s father makes her read the statute aloud to be sure she understands. A student of the Black nationalist Marcus Garvey, he is committed to developing “self-sufficiency in the Negro race by the practice of separatism.” Jack is a threat.

And Jack knows it. Time and again, he resolves to break things off. But some counterforce — fate or grace or willfulness or love — keeps bringing them back together. Jack writes a letter of farewell, then tears it up. He walks to Della’s, rehearsing the breakup, only to find her sitting on her stoop. “I prayed you would come,” she says. Della’s sister shows up and takes her back home to Memphis, Tenn. “We did end it,” Della says when Jack comes home one night to his shabby rented room to find her waiting on his bed. “It just wouldn’t stay ended.”

Jack agonizes. If he leaves Della, he will break her heart; if he stays with her, he’ll ruin her life. The choice is impossible. Haunted by the memory of the girl and child he once forsook, Jack has committed himself to a life of harmlessness. The only way he can succeed is by keeping to his lonely self. Whenever he entangles himself with someone, pain ensues. He seems fated to cause harm. This is the conundrum of his life.

At the heart of the book is a question of redemption. “Can these bones live?” Jack asks himself in the graveyard. Can people change? The question extends beyond the individual to society at large. Jack reads in the newspaper about a plan to demolish a Black section of St. Louis in the name of urban renewal. Forty Black churches and countless homes are slated for destruction. The real sin that holds Jack and Della apart is not theirs, but America’s. Can these bones live?

In her political writing, Robinson frequently appeals to the notion of love. “What does it mean to love a country?” she asked in a recent New York Times essay. “Human beings are sacred, therefore equal. We are asked to see one another in the light of a singular inalienable worth that would make a family of us if we let it.”

Della sees past Jack’s excuses, his faithlessness, his inadvertent harms. In a scene that brought me near tears, she tells Jack why she loves him: “Once in a lifetime, maybe, you look at a stranger and you see a soul, a glorious presence out of place in the world,” she reflects. “And if you love God, every choice is made for you. There is no turning away. You’ve seen the mystery — you’ve seen what life is about. What it’s for. And a soul has no earthly qualities…no guilt or injury or failure. No more than a flame would have. There is nothing to be said about it except that it is a holy human soul. And it is a miracle when you recognize it.”

This is the crux of Robinson’s theology: an invitation to see every person as Christ would see them, holy and human, sacred and flawed. Perhaps part of the reason I love her novels is because they seem to be working out a question that every serious person of faith must ask: how can my faith account for another person’s spiritual experience that contradicts my own? Della acknowledges the brightness of a soul who will never share her faith. John Ames marries Lila, a drifter and former sex worker. He baptizes her, and she sneaks down to the river to wash the baptism off.

In many ways, I’m unlike Jack. I don’t share his tendency toward trouble; I’m not shackled by my own sense of failure. Yet I too am a prodigal son. I’ve renounced beliefs the rest of my family hold sacrosanct. Does grace extend to me? Marilynne Robinson believes it does.

***

This story first appeared in Broadview‘s March 2021 issue with the title “An impossible love.”

Josiah Neufeld is a journalist and fiction writer in Winnipeg.

“This is the crux of Robinson’s theology: an invitation to see every person as Christ would see them, holy and human, sacred and flawed.”

Here the writer’s Christian theology is wrong. 2 Corinthians 5:17 states: Christ only sees those in the manner she describes; need to be “In Christ”.

“How can my faith account for another person’s spiritual experience that contradicts my own?”

Apart from Christianity it can’t. There is one body, and one Spirit…one Lord, one faith one baptism; one God and Father of all…” (Ephesians 4:4-6)