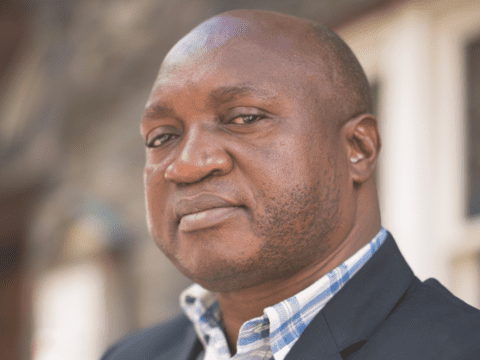

The journey from a murderous civil war in Kalemie, Democratic Republic of Congo, to the tranquil shores of Georgian Bay, Ont., is 15,000 kilometres. For three years, Gustave Kemu, now 48, his wife, Arlette, 40, their son, Landry, 14, and three daughters — Audrey, 12, Vanessa, 8, and Benita, 4 — made that uncertain, desperate sojourn, sustained only by their faith and each other.

The exodus from horror to liberty was marked by violence: the eldest Kemu daughter, Jacquie, then 16, was raped and murdered as her mother and siblings watched helplessly. The trek was one of privation: the family slept on the ground and ate only beans and rice. The family was flotsam on a tide of 2.3 million refugees fleeing a crisis that has claimed over five million lives in the past dozen years.

But the three-year saga that brought the Kemu family from Kalemie on Lake Tanganyika to Thornbury and Clarksburg in the municipality of The Blue Mountains, Ont., ended finally in a swell of warmth and generosity. Against all odds, the family has found freedom and peace in Canada. “We are here only by the grace of God,” Gustave says.

Arlette and Gustave met at university in Lubumbashi in the late 1980s. She studied biochemistry, and he studied sociology, history, geography and French. The couple married in Lubumbashi in 1990. After they graduated, they moved to Kalemie where Arlette worked as a salesclerk in a small shop. Gustave became a schoolmaster, but the government paid its civil servants very little when it paid them at all. They lived a modest life but were able to send their children to a good school.

Sporadic conflict waged by militia and rebel factions became a fact of life in the eastern Congo after the Rwandan genocide of the 1990s. The violence moved from one area to another as rival groups pillaged the country’s wealth of natural resources. In May 2007, the fighting came to Kalemie.

Gustave and Arlette decided the family must flee to survive; Gustave went north to the port of Goma to secure passage across Lake Tanganyika and out of the country. The family remained separated for several months. After Gustave left, marauding rebels raped and killed Jacquie in front of her mother and siblings.

Abandoning their home, Arlette and the surviving children walked and hitchhiked the 600 kilometres to Goma, then travelled for three days to northern Zambia in a freighter full to the gunwales with refugees. They continued on by truck for three days, journeying out of Zambia and then across Zimbabwe. Gustave had taken the same escape route a few days ahead and made arrangements for them with brokers who supply transport and meagre rations for a fee.

Landry, then 12, vividly remembers standing packed together in the truck. “We swayed from side to side, and all that kept us from falling is that we were shoulder to shoulder,” he recounts, mimicking the swaying motion. Adds his mother, “We stopped only to eat small meals cooked on a small gas stove by the driver. We slept on the ground beside the road without blankets.”

They finally arrived at a UN refugee camp in the Chiredzi game reserve in southern Zimbabwe, where they were reunited with Gustave. But the joy of reunion was overshadowed by having to break the news to him of his eldest daughter’s death.

The camp rations of sugar, cooking oil and flour were inadequate, so the Kemus, like most refugees, relied on their entrepreneurial talents to supplement their income and diets. Landry says that the boys went into the forests and picked wild fruit to sell.

“We prayed and often we fasted,” Gustave recalls. Some of their prayers asked God to explain their predicament; some were requests for deliverance. “We had such faith and were so optimistic at each step of the settlement process that we became a laughingstock to others in the camp,” he says. After two years of waiting, the Kemus were cleared to go to Canada.

In late 2008, a young Anglican minister, Rev. Canon Stephen Haig, arrived at St. George’s in Clarksburg, Ont., a village adjacent to Thornbury. Both communities were once rural mill towns, places where grain was ground and lumber sawn.

Now an affluent enclave with a liberal outlook, Thornbury has a long history of helping people. African Americans first found refuge and freedom in the area 175 years ago when the shores of Georgian Bay became the northern terminal of the Underground Railway. Thirty years ago, Grace United in Thornbury sponsored four Vietnamese refugee families, and two have remained in the community.

Haig had spent 10 years in Leamington, Ont., and been part of a committee that brought 40 refugees to the area in about six years. He was determined to continue his ministry of refugee sponsorship, and his new congregation was willing to act, but not on its own. So Haig reached out to an ecumenical community of Christian churches.

The Kemu family sponsorship took wings when Haig connected with Baptist ministers Bill and Sharon Chapman and former Catholic sisters Adrienne Corti and Rita Mary Coté. Leadership of the refugee committee shifted from Haig to First Baptist minister Sharon Chapman.

Six congregations ultimately participated: St. George’s Anglican, First Baptist, St. Paul’s Presbyterian, Blue Mountain Community (Free Methodist), Grace United, and St. Vincent Roman Catholic in nearby Meaford.

“We struggled with many issues,” says Rev. Brian Goodings of Grace United, a member of the refugee committee. “At times we were a bit paternalistic. It felt a bit like awarding a lottery. We asked, ‘Should we bring a black family that speaks French and Swahili to a white English small town?’ and ‘What difference does one Congolese family make when there are more than a million who need a place to live?’ I admit I was skeptical.”

But it was the right decision, he asserts. “This has transformed people in this community in a way that simply writing a cheque could not. And for the Kemus, it has made the difference between life and death.”

The biggest obstacle in the sponsorship process was finding affordable housing for the family, says Sharon Chapman. Then Melinda Burke offered to lease her home, which has housed four generations of Burkes, to the committee. “My mother, Doris Burke, a member of Grace United, was involved 30 years ago when the church sponsored four Vietnamese boat refugee families to come to the Thornbury area,” says Melinda. “If she were still alive, my mother would be a member of this committee.”

As word got out about the project, church members and the secular community responded with enthusiasm. “Thirty people volunteered countless hours to prepare the home,” says Corti. “Three couples, neighbours, shopped for practical staples. Another couple with two complete rooms of Canadiana furniture in storage had movers deliver it to the home. School children were particularly generous, providing new winter clothing, school supplies, gift cards for food and other needs, and bicycles for each family member.”

Some people volunteered to drive the family, to take them shopping, to give English tutorials, to help with the myriad practical details of learning about life in Canada. One family pooled its Christmas gift money for the Kemus rather than buying each other gifts; a hairdresser spent her tips on winter underwear for the children. Says Corti, “The list could go on and on about the open hearts and generous spirit of the members of this community.”

The Kemus had no idea of the welcome that awaited them when they landed at Pearson International in February after 15 hours in the air. They told the Canadian immigration agent they only knew that they would not be living in Toronto.

“We’ll let you go through the doors of the international arrivals area,” said the agent. “But if no one meets you, you’ll have to come back until we get you sorted out.”

Outside the door was a busload of people from Thornbury with a sign in Swahili that read “Welcome Kemus.” There was a translator, warm winter clothes and cookies. And there was freedom and safety.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s June 2010 issue with the title “‘Here by the grace of God.’”