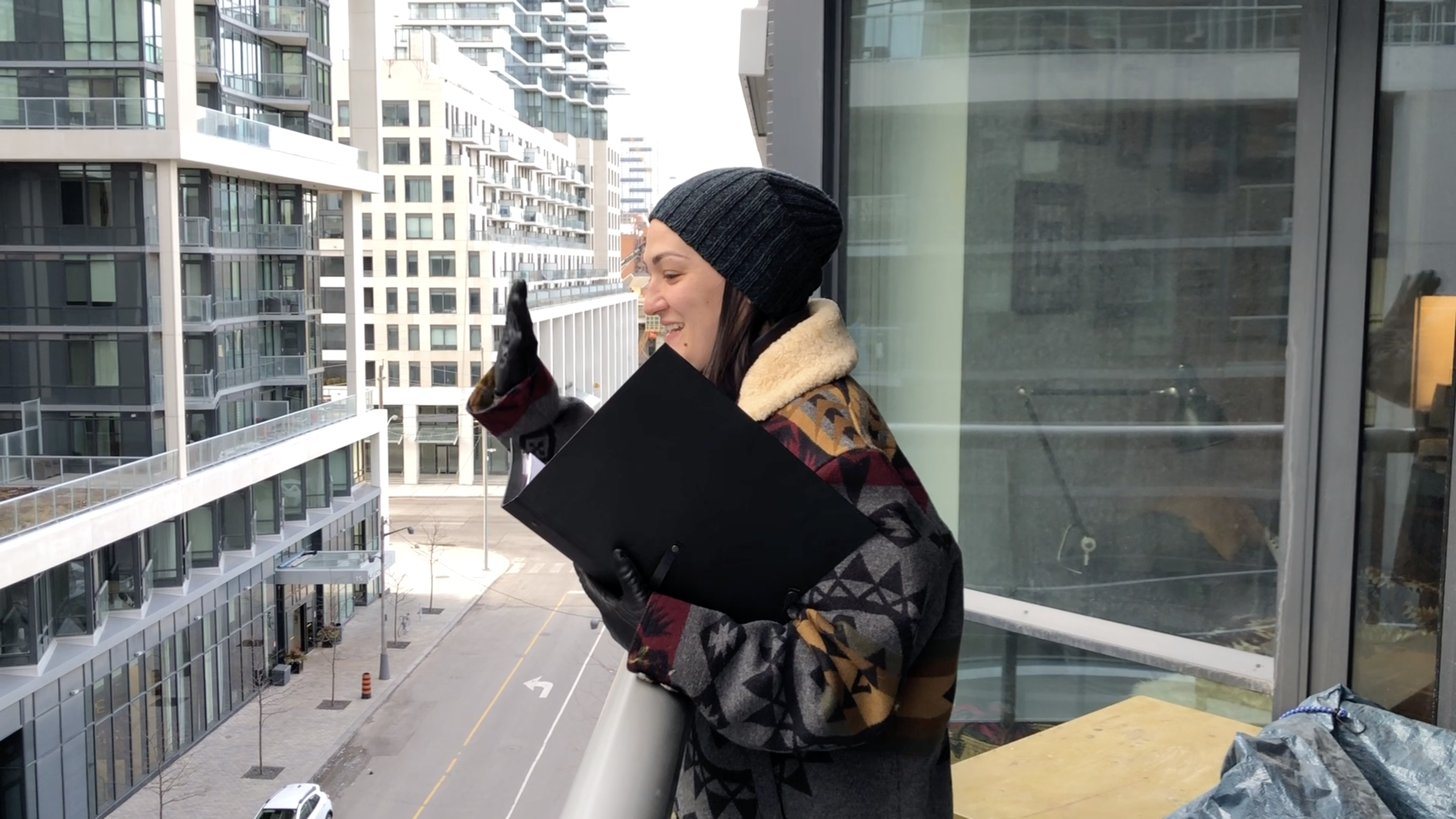

Teiya Kasahara leans over their balcony in Toronto, their diamond-strong voice slicing through the cold breeze to reach neighbours across the street. The opera singer and multidisciplinary performer raises their arms in supplication as they sing Ave Maria, accompanied by pianist Andrea Grant two floors down.

Summoned by the serenade, condo dwellers venture onto their balconies, and joggers stop in their tracks and look up. Kasahara waves.

Their performance that March day was the first of 19 shows; the total number of performances is inspired by the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. “I wanted to do something positive in this panic,” says the singer, who uses the pronoun “they.”

This gesture of goodwill is just one of many springing up globally in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Canadians have stepped up to the plate. Restaurant owners are giving away meals and strangers are delivering groceries to those in isolation. Hamilton, Ont. band Arkells is offering free music tutorials for those stuck at home. In these strange times, altruism has become appealing — and the science of compassion provides some clues for why we strive to help.

Toronto psychotherapist Victoria Lorient-Faibish has noted a rise in compassion. Facing down the universal, external threat of the coronavirus has unified people across the globe. “We’re all in this together,” she says. Acts of compassion are spiking alongside this feeling of unification and recipients of these gifts are comforted by the realization that they matter.

Lorient-Faibish says compassion also benefits the giver. When the pandemic hit home, many Canadians were overwhelmed by anxiety. Those who engaged in helpful activities felt empowered, while tending to others also yanks us out of self-centred, negative ruminations and binds us together. “There’s a massive benefit all around,” she says.

More COVID-19 coverage on Broadview

How I grapple with sacrifice during Lent and COVID-19

How COVID-19 is affecting Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside

How I’m practicing community care in isolation

Cobourg, Ont. town councillor Nicole Beatty has experienced this effect firsthand. Shortly after the pandemic became headline news, Beatty’s partner, whose compromised health increases his risk for infection, fell ill with a bug akin to “five flus.” As she sat with him in the hospital, Beatty’s heart began to race. “I saw how (COVID-19) could take someone out,” she says.

Then the community leader went into problem-solving mode. While she didn’t know how to safeguard her partner, she had a gift for mobilizing volunteers to aid the region’s most vulnerable members. After discovering that two other Cobourg citizens were already pursuing similar agendas, Beatty joined forces to create Caremongering Northumberland, a virtual neighbourhood network matching those needing services with benefactors.

Beatty’s dedication to others has provided a welcome distraction. “(It’s) a coping response to my own mental health ….otherwise I’d be on the floor thinking the world is ending,” she says.

Plus, witnessing the group’s good deeds makes her feel optimistic. “It gives me hope…knowing that we are going to weather this storm,” she says.

Scientists who study compassion are pinpointing the mechanisms behind this “helper’s high.” Nature has hard-wired us for nurture, rewarding compassion with a flood of pleasurable chemicals, says neurosurgeon Richard Doty, founder of Stanford University’s Centre for Compassion and Altruism Research. Acts of kindness dial down our stress, heart rate and blood pressure, Doty says. They also unleash a surge of dopamine, the “feel-good” brain chemical, as well as the “cuddle hormone” oxytocin, which triggers a sense of belonging.

Kasahara’s compassion has helped them cope with the shock of lost gigs and income due to COVID-19. Though the performer battled icy blasts and faulty acoustics outdoors, the audience’s response made the effort worthwhile; strangers refuelled the singer with surprised smiles, rapt attention and honking horns.

This interplay of intimacy continued long past each show, as videos of the concerts went viral on social media, and Kasahara was inundated with muffins, chocolates and grateful emails from new fans.

“It’s heartwarming and powerful to know that we can still connect on something as simple as a …song,” they say.

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

The church ought to be more theologically precise about the use of the word compassion. Is that not supposed to be the language we use to interpret reality of “suffering”and our response to humsn suffering? As Christian’s we expect our leaders to meditate on compassion through Christ. And ultimately through him crucified. We might use the word compassion of ourselves more sparingly and with greater humility. And therefore it would have more meaning when we see it. It has become domesticated. Compassion literally means to suffer with someone. Jesus from the cross revealed God’s compassion. When I think of that I realize all my good deeds to help are just that. I don’t dare compare my good deed to God’s compassion in Christ. Christ is the origin for the church’s meditations on compassion. If you are hearing something else about compassion from the pulpit please read the passion story of Christ youreslf for the gospel. And than we do all the good we can.