Within a single week in July 2022, Rev. Stephen Fetter was present at the death of two longtime members of his congregation, Forest Hill United in Toronto.

Both chose to die with medical help. Those were the first times Fetter had walked anyone through the medical assistance in dying (MAID) process, legal in Canada since 2016. Both deaths left an indelible mark.

The first he describes as “classic MAID.” Paul Cutler, a church board member and lifelong congregant, was diagnosed with cancer in 2020 and was soon in palliative care. “He said to me, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore. This is taking too long. I am taking up a bed that someone else needs,’” Fetter recalls.

The other death wasn’t so tidy. “He was one of the most abused people I’ve ever known. He grew up in poverty, was sexually abused, came from a broken family,” Fetter says of Michael Fraser, whose death was detailed in a 2022 Toronto Star article. “He flirted with suicide for as long as I knew him, which was nearly 30 years.”

Joining Forest Hill gave Fraser a new lease on life, Fetter says. “He had a remarkable turnaround for about 15 years, before the scars of abuse caught up with him. His [post-traumatic stress disorder] got worse, the nightmares came back. His liver was toast.”

By January 2022, Fraser was talking with his partner and Fetter about seeking MAID. He wanted Fetter to help him lobby his doctor for it. It took the minister three months before he was on board with Fraser’s request. If MAID hadn’t been an option for Fraser, Fetter believes his congregant simply would have killed himself — an act that would have been far harder on his partner. But witnessing MAID in action also took a toll on Fetter. “I haven’t stopped thinking about the deaths,” he says. “They just knocked me off my feet.”

MAID has been growing steadily for the past seven years but is still relatively rare in Canada. In 2021, just over 10,000 people chose a doctor-assisted death, representing about three percent of deaths. Ministers are among the key frontline workers who help people navigate their own dying and death. But some faith leaders are discovering that MAID is murky, both theologically and emotionally. Adding to the confusion is how quickly the laws are changing. Canadians no longer need a terminal diagnosis to get approved for MAID. People suffering solely from mental health can be approved for MAID, starting next March. How can clergy keep up?

MAID first made national headlines in 1992, when prominent assisted suicide activist Sue Rodriguez, suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, asked in a taped statement to members of Parliament, “If I cannot give consent to my own death, whose body is this? Who owns my life?” In 1994, Rodriguez chose a then-illegal assisted suicide. More than two decades later, in 2015, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that assisted suicide did not violate the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, clearing the way for Ottawa to pass a new law. By 2016, the law allowing MAID was in place.

In response, the General Council Executive of The United Church of Canada issued a statement on MAID in 2017, urging a “cautious approach by legislators and medical professionals implementing these laws, as well as by individuals, families and communities of faith who are considering making use of this new legislative option.”

In 2021, Canada began allowing a new group to use MAID: those without a terminal diagnosis. To access a physician-assisted death, a person must be at least 18, eligible for health care, able to give voluntary, informed consent, and “have a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability (excluding a mental illness until March 17, 2024); be in an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability; [and] have enduring and intolerable physical or psychological suffering that cannot be alleviated under conditions the person considers acceptable,” according to the federal Ministry of Justice.

For Rev. Christopher Levan, the decision to allow MAID for those who are not near death represents a profound shift — and one that puts clergy who get involved on unstable theological ground. A retired minister in Salt Spring Island, B.C., Levan explains how MAID laws have changed since 2020 when he published the MAID-positive Healing Death: Finding the Healing to Live Well into Our Dying. In the book, written mainly for clergy and lay leaders, Levan came to the conclusion that MAID can be a theologically sound part of the palliative spectrum. Today, he sees “the edges being pushed.” Says Levan, “I hear, ‘I have a right to this [medically assisted suicide].’ That turns your life into an object that you possess. I understand that as part of liberal individualism, but it’s not biblical. Life is a gift. Your job is stewardship.”

He notes that there has been no formal United Church pastoral pushback that he knows of against offering MAID to Canadians without a terminal diagnosis. He hopes that the legislative change wakes people up — both inside the church and outside of it.

More on Broadview:

- Canada’s updated MAiD program is appealing to ‘desperate’ Canadians, advocate says

- Manitoba’s first medically assisted death in a church was an ‘intimate’ ceremony

- In some families, medical assistance in dying is anything but a peaceful ending

“As church leaders, we can offer depth” to discourse about death, suicide and MAID, he says. Levan predicts that within 20 years, Canadians will understand what permissive MAID laws mean for society. “I think [faith leaders] will have a great deal to offer the world when it has decided that secularism doesn’t cut it.”

In Toronto’s North York neighbourhood, Rev. Roberta Howey works with Canada’s least religious generation — youth and young adults — at Lawrence Park Community Church. Young people, she says, are keenly aware of the deficits in Canada’s social fabric, such as affordable housing or support for people with disabilities. At the same time, they’re aware of how much government and social effort MAID has absorbed. “It’s dystopian,” Howey says. Some young people she knows interpret the law as, “I’m sorry there’s no food for you, but we do have MAID.”

Youth interest in discussing MAID is part of why she produced a two-part podcast on the topic for her congregation’s podcast, The Rooster Crows, with colleague Rev. Stephen Milton. Her guests include Heather Morgan, a disability advocate; Anne Simmonds, a nurse and an ordained minister whose views on MAID have evolved over time; and Susan Desjardins, co-founder of Dying with Dignity’s Ottawa chapter.

Regardless of how we feel about MAID, we can’t dismiss it, Howey says. “At first when people started choosing MAID, it was whispered about. It wasn’t quite shame, but it’s not something they wanted to broadcast. We’re seeing it in the obits now, in ‘funeral’ services before the person passes away.” Howey hopes ministers are able to get much more training on the subject. “The challenge is it’s changing at a blinding rate.”

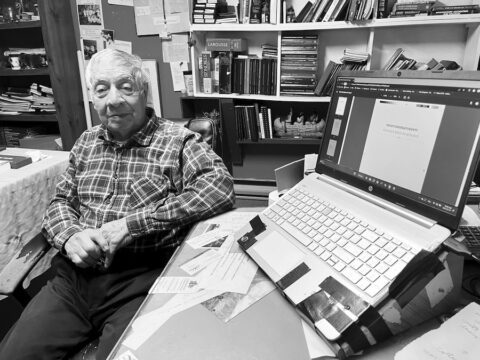

Fetter echoes the need for more training. As the General Council’s program co-ordinator for e-learning, he has been urgently asking the national church for liturgical resources for ministers who are walking folks through MAID. “I think we need to wrestle with what is sin, what does salvation look like, what is mercy? All these big theological questions are wrapped up in this,” he says.

The United Church of Canada released an updated statement in 2020 in reaction to the impending legislative changes, recommending that “foreseeable death” be maintained as a criterion for accessing MAID.

Since 2017, General Council staff have planned to produce materials for clergy and congregations on providing pastoral care to those considering or going through MAID. COVID derailed much of that work, according to Rev. Jennifer Janzen-Ball, the executive minister for theological leadership. National staff are planning to produce webinars, she says, but there is no timeline at this point. Without many resources in the hands of clergy, MAID laws continue to evolve, and MAID deaths become more common.

Although he has been conducting funerals for every kind of death for decades, Fetter still weeps when he discusses the two medically assisted deaths he witnessed in July 2022. He misses both men. He trusts they’re both in God’s hands and relieved their pain is over. At the same time, he says, MAID isn’t like other deaths — yet. As a society and a faith, he says, “We’re living with thousands of years of human history that said suicide is a sin. Even if you say you no longer believe that, it’s the water most of us still swim in.”

While MAID has forever changed Fetter’s work as a minister, one constant for him is the fundamental role of clergy when helping people face death. “Pastoral care is about helping people find meaning,” he says, “to be a representative of love as we encounter the really tough stuff.”

***

Pieta Woolley is a journalist in Powell River, B.C.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s September 2023 issue with the title “Ethical Ends: MAID laws keep changing. How can clergy keep up?”

With all respect to my colleagues, liturgical resources may be useful and helpful, but they are nothing unless we have come to our own understanding of the meaning of life, death and, yes, sin. Without that foundation we are not well equipped as pastors to walk with others on their journey. It is a deeply and profoundly difficult thing which is demanded of us. Perhaps, instead of liturgical resources, the denomination might better offer its pastors time and space for reflection, learning and spiritual care for each other to better equip us spiritually and practically to care for others in these new realities.

Suffering and autonomy are two of the most important words to be used when discussing medical assistance in dying (MAID).

When a person is desperate for death, it is to escape suffering; it may be physical pain that is unbearable, or it may be the emotional pain of being helpless and trapped in a body that no longer supports the person. There is some suffering that only death can end. This is a human rights issue. We must have the right to determine how much suffering we will endure. Are those who suffer from intractable, serious, mental illness not worthy of their Charter rights?

What happens when healing is not an option? The increase in the number of MAID recipients means a decrease in the number of Canadians forced to suffer against their will.

Suffering people know that they need. Our role is to listen with love and an open heart.

Very powerful and still very little. I am amazed that the United Church of Canada has not moved more quickly to create the needed resources to support their clergy and lay staff in helping those choosing MAID.

The process of supporting someone you love in completing the MAID journey feels very lonely, and without clergy support, how do we find the faith we need to keep one another in a space that best supports each of us where we are?

Just a small quibble: People do not suffer from mental health, they suffer from mental illness.