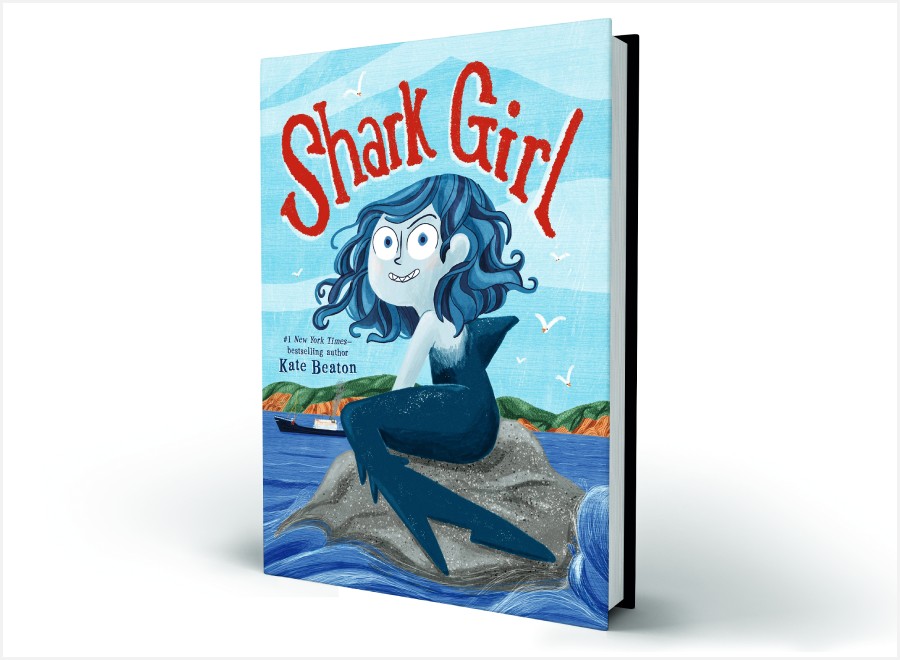

Kate Beaton is a best selling author and comics artist in Cape Breton, N.S. Her webcomic Hark! A Vagrant caricatured historical figures from Napoleon to Ada Lovelace and was one of the first webcomics to achieve worldwide recognition after its debut in 2007. More recently, her graphic memoir, Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands, documented her experience working as a young woman in the Alberta oil patch. The book won the 2023 edition of CBC’s Canada Reads. Her new children’s book, Shark Girl — a spin on Hans Christian Andersen’s classic mermaid tale — releases in late February. Beaton spoke to Kate Spencer about creativity, fish and the false meritocracy of art.

Kate Spencer: You’ve spoken recently on how social class affects how likely a person is to make art. Tell me about that.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Kate Beaton: It’s well documented that if you come from wealth or privilege, the likelihood of you becoming an artist is far greater than if you don’t. It affects whether you think you can be an artist or not. You not only have to have the drive to do it, but you also have to contend with how low paying it is as a field. A lot of people in working-class and poor areas, they just don’t do it. Once you’re in the art world, you look around and realize how many of your peers — despite appearing to live the poor artist’s life — came from very financially secure backgrounds. It’s not something anyone wants to acknowledge because we like to think that art is a meritocracy, but it’s not.

KS: How did your commitment to a life of making art take shape?

KB: A dedication to a life in the arts was not something I necessarily had in the beginning — I was focused on finding a way to make money. I had dreams of working in art in some way, but I was from rural Cape Breton; there was no roadmap for that life, no one to tell you it was possible. The only thing people were invested in was to get somewhere with some sense of security.

I didn’t read a comic book until university, where there was a very small collection of graphic novels. I started doing comics for the school paper because I wanted to draw, and then I enjoyed the feeling of making something people enjoyed.

KS: Tell me more about life in Cape Breton.

KB: People saw Cape Breton as this postcard where people are flattened into a commodity, with fiddles and tartan and fishing boats largely there to be consumed in some way by the visitors. Or they thought of Cape Bretoners as a drag on the Nova Scotia economy, people fighting to keep coal mines open when they should be closing, cashing their unemployment cheques and things like that. They’re very different images, but it’s the same location.

It’s a funny thing to wrestle with — you have your little world, and you look out, but there are always people looking back in. And often in Cape Breton, the people looking back have more than you do. It made me think a lot about the effect of tourism on culture, how you value things because they’re more sellable.

KS: How does growing up in a place with dualities like that impact the art you make?

KB: If you’re from a place where you’re thinking about questions of identity and perception, you’re talking about stories. If your understanding of yourself in the world is super straightforward, I don’t think you wrestle with some of the questions that make stories worth reading. Cape Breton is full of stories of people coming and going and wanting to come home. There’s always this grand narrative arc of wanting to come home.

KS: Do some of these themes show up in Shark Girl?

KB: Shark Girl is half-human and half-shark, like a mermaid but a shark. She’s not what you’d think, necessarily. Our perception of sharks as fearsome killers is what leads to their mass endangerment. In reality, they kill a few humans a year, but thousands of sharks die each year by our hand. Shark Girl is a feisty little thing who gets caught in an evil captain’s net and decides she must have revenge. I made the captain a real bad guy — greedy and mean to his employees and with bad fishing practices. The boat is based on the Cape Sable trawler at the Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic; they sent me blueprints and reference images. And all the species of fish in the book are from Nova Scotia. It’s not explicit, but as you read it you see it is a Nova Scotian book.

KS: How did the process of writing a story for children differ from writing works aimed at adults?

KB: It’s just as hard, and children are just as smart and discerning as an adult audience. Kids will not tolerate a bad book. If it’s too wordy or boring, they will tell you. And you remember your favourite book from when you were little, whereas I don’t remember what I read six months ago. If you make something that means a lot to them, they will carry it with them always. What a privilege that is for an author. You also don’t know what they’ll take away from it. They’ll be obsessed with one detail in a corner that you never even thought about. They look at everything on the page.

More on Broadview:

KS: What’s next for you in your creative life?

KB: I will have more children’s books coming and also more fictional stories that are set in the culture I know. You don’t have to write what you know — you can write about outer space or something. But I think I come from a storytelling culture, and I didn’t investigate that part of myself and my work for a very long time. So I want to dig in there a little bit.

I do hope I will make a story that is set in Nova Scotia. Ducks was a story about the East Coast, but it was about being uprooted from that community. I would like to show in my work that there are a myriad of identities and feelings about these places.

KS: What advice would you give to people trying to make a place for themselves creatively?

KB: If you have a unique voice, pursue that. Pursue what makes you stand out. We have so much media that are versions of one another. When someone with a wholly unique voice comes out, people really turn their heads.

I had a great benefit there because I didn’t know anything about comics, so my work didn’t look like other comics and it didn’t sound like other comics. I never took an art class, really, which ended up being a strength. Because my work was different, people found it and liked it. You need to think about the things you do have and that you do well.

***

Kate Spencer is a writer in Halifax.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity. It first appeared in Broadview’s March 2025 issue with the title “Art of Place.”