The proportion of people who report being Muslim, Hindu or Sikh in Canada has more than doubled in the last 20 years largely due to immigration, Statistics Canada’s recent census data shows.

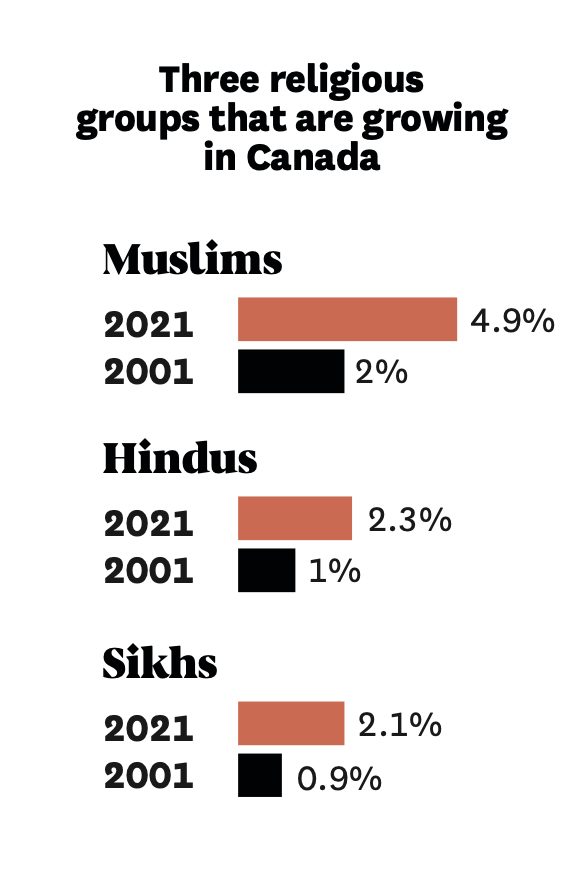

In 2021, Muslims — the largest religious group after Christians — made up 4.9 percent of Canada’s population of roughly 37 million people compared to just two percent in 2001. During the same time period, the share of Hindus jumped to 2.3 percent from one percent, while the proportion of Sikhs grew to 2.1 percent from 0.9 percent.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

“It’s pretty much all coming from immigration, along with higher birth rates amongst immigrants,” says Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme, an associate professor at the University of Waterloo whose research explores trends in religious identities.

She adds that these religions will continue to grow along with immigration, especially with the federal government promising to accept about half a million newcomers every year through 2025. In keeping with current patterns, many future immigrants are expected to arrive from South Asian countries (particularly India), where Hinduism, Islam and Sikhism are common. Still, the overall number of people reporting affiliation to one of these three religions remains relatively low (3.4 million people) compared to those who report Christian affiliation (19.4 million) and no religious affiliation (12.6 million).

While other world religions are growing in Canada, Christianity is on a downward trend across all Canadian denominations, except Orthodox Christianity. “In the case of Orthodox Christianity, we’re gaining heavily from immigration from Eastern Europe, Greece and Russia. And moving forward, it looks like — because of the geopolitical situation currently — we’ll be accepting, and have already started accepting, a large number of Ukrainian refugees,” Wilkins-Laflamme says.

Religious affiliation will become more diverse across Canada, not just in big cities. Most newcomers still prefer to settle in Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal, according to census data. Typically, immigrants choose Canada’s major urban centres because there are more job opportunities, better infrastructure and services and existing social networks. However, the overall share of new immigrants who are settling in Canada’s three largest cities is declining. About four percent chose to make their homes in smaller urban areas, and three per cent chose rural areas instead.

“I think the high cost of living is pushing everyone out of hot spots, including immigrants,” says Wilkins-Laflamme. “In areas that haven’t necessarily seen much diversity … they’re definitely seeing more in the last year, so that’s a key trend — a move out of the big cities. But that was also helped by the pandemic since some people can do remote work.”

Shaila Carter’s family is all too familiar with these trends among immigrant families in Canada. The 48-year-old second-generation Canadian Muslim says her father initially immigrated to Toronto from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in the late 1960s because that was where “everyone” went. But in 1981, he moved their growing family northwest to Brampton, Ont. — a small, mainly Christian town at the time — to buy a home.

Brampton had no mosque then, so they would drive to Toronto to celebrate Eid. “And then all of a sudden, I think in the ’90s, there was this influx of immigration,” Carter says. “We just started seeing a lot of Muslims and Sikhs.”

More of Broadview’s census coverage:

- Why over a third of Canadians now claim to have no religion

- The United Church’s numbers have dropped more than any other denomination

Gradually, Brampton grew to offer numerous places of worship, faith-based schools and services catering to tens of thousands of South Asian immigrants. For Carter’s parents, this growth was important as they became increasingly religious.

Five years ago, the cost of housing also led Carter and her husband to move their family from Brampton to the small town of Shelburne, Ont. But three years in, she says they wanted to leave because they felt lonely with so few other Muslims around — until the demographics started changing.

Indian and Pakistani immigrants started buying farmland in the area, and the first mosque opened in 2022. “As soon as they started the mosque and [religious] lessons, I started feeling a [sense of] community,” Carter says. She has also begun to share her cultural traditions with her non-Muslim neighbours.

Not everyone finds belonging like Carter. Sadly, Islamophobia is on the rise in Canada. Hate crimes against Muslims increased by 71 percent in 2021 alone. The province of Quebec also passed the controversial Bill 21 in 2019, banning many public sector employees from wearing religious symbols in the workplace. Some feel this law is directed at observant Muslims.

Wilkins-Laflamme says there isn’t enough data to support the idea that Muslim immigrants, many of whom are emigrating from former French colonies, are avoiding Quebec because of it. “Usually the economic factors, and potentially the language factor, are more important,” she explains.

***

Sanam Islam is a freelance journalist in the Greater Toronto Area.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s June 2023 issue with the title, “Religion on the Rise.”