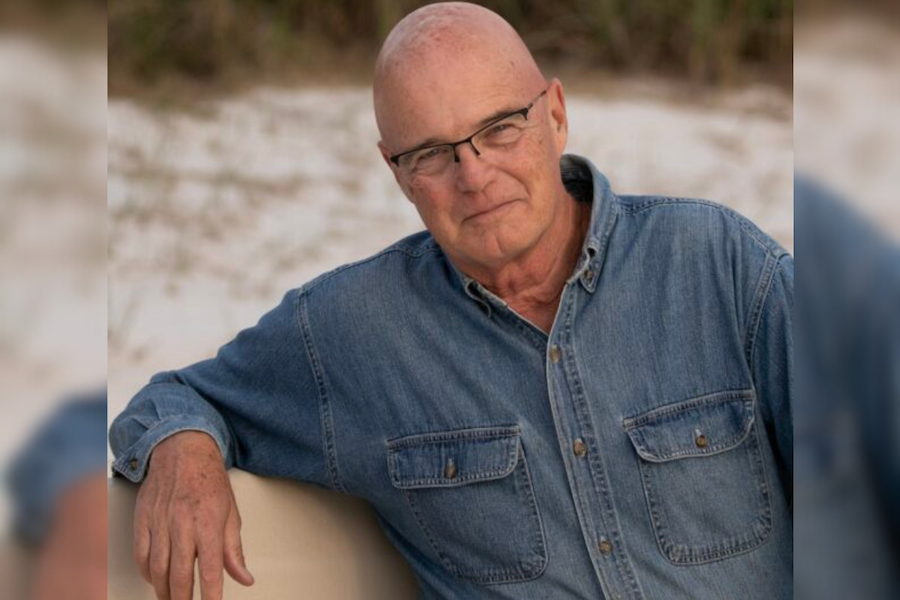

In 1999, a young parishioner at the church where Brian McLaren was a pastor asked him a question that changed his life: had he ever heard of global warming? He hadn’t, but it would quickly become a topic he’d spend a lot of time thinking about. In 2007, McLaren published Everything Must Change — his first book to touch on the subject.

His latest work, the provocatively titled Life After Doom: Wisdom and Courage for a World Falling Apart, which comes out in May, isn’t your typical climate change book. Rather than ending with the conclusion that things are bad, McLaren begins with it. Then, he guides readers through how to accept the ways that climate change is impacting the earth, and what they can do about it.

Though McLaren cautions that hope is complicated, this is ultimately a hopeful book — it is, after all, about what comes after doom. I had the chance to talk to him shortly before Easter, which felt timely because, in a way, Christianity is centred on the idea of life after doom: Jesus dies, then he returns. There is hope even when things seem utterly hopeless. But, as McLaren says, Christians would do well to focus on life here on earth as much as they aspire to life that comes after. Here, he shares his thoughts on climate despair and how to keep faith during dire times.

Anne Thériault: Who is the intended audience for Life After Doom?

Brian McLaren: I wrote this book for people who feel overwhelmed. They look at what’s going on with climate change, in what many are calling our multi-crisis, and when they read the word “doom” in the title, I hope they feel a sense of relief — that they think, oh, maybe somebody’s taking the way I feel seriously.

AT: I really like that it’s called life after doom, in part because I think our conversations about climate change can be a bit nihilist, and it can be hard to engage with that.

BM: I struggled with this myself. As I was going deeper into my research, I noticed that one of my biggest problems is my own brain. It goes from one extreme to the other. The optimistic side says, “everything will be all right, technology will solve it, the human spirit will solve it,” while the opposite side says, “it’s hopeless, it’s too big of a problem.”

I realized I wasn’t necessarily seeing reality — I was seeing what my brain most easily gravitates towards. I became especially suspicious because both deep optimism and deep pessimism lead to the same result: apathy. Something in me said that’s probably a glitch in my brain, that it would be far wiser to look for agency in the middle of the climate emergency.

More on Broadview:

- How should we navigate the climate crisis

- How to deal with the end of the world

- Canadian mining companies are destroying communities in the Philippines but this United Church mission team is determined to help

AT: You write about growing up in the Plymouth Brethren church, which is the tradition that came up with the idea of “the Rapture.” How have those teachings influenced your view of climate change?

BM: Because I grew up in a tradition that was rooted in this view of the future — the theological word for it is called eschatology — I got a front row seat at how ways of thinking about the future can be used to manipulate people, or direct people to harmful behaviours. I’ve watched how this kind of spirituality made people act in a very cavalier way about the entire created world. The only thing that matters is souls, how souls go to heaven when they die and how we keep souls as pure as possible between now and then. It’s such a different way of looking at life than saying that we have a responsibility to care for the earth.

AT: How have biblical texts shaped your view of climate change, and conversely, how has climate change shaped your view of biblical texts?

BM: Unfortunately, I don’t think biblical texts shape anybody’s thinking as much as people claim they do. What happens is economic, political and social ideologies train people to use certain biblical texts to reinforce those ideologies.

I feel like it took me two thirds of my career to get to a place where I could even begin to see what was there in the Bible all along. For example, in the very first chapter, we find God pronouncing the earth good. Good means having inherent value, and creation exists before there are people. There is inherent goodness in the world, apart from people and apart from religion. But I was always taught to look at one verse in that chapter that speaks of humans having dominion over the earth. And dominion was understood as a carte blanche to do to the earth whatever we want, for our benefit.

What has happened to me, in the writing of this book, is I’ve gone back and done a survey of the whole Bible from beginning to end as an ecological text. What has become clear to me is that the Hebrew people, as the Bible was taking shape, were land-rooted people who were resisting being colonized by imperial powers around them. And as they were resisting empire, they were trying to hold on to deeper values that had to do with a deep connection to the land. It strikes me how much we need to restore not only our connection to the earth, but our very existence as part of the earth. We’re not just saying we need to value nature — we need to understand we are part of nature. We are nature caring for nature.

AT: What is your advice to help people from falling into despair over climate change?

BM: I feel that both hope and despair are complicated. Both can lead to action, and both can lead to paralysis, or apathy, or complacency. We have to learn how to hold both hope and despair as part of our way of dealing with reality, and I think there are two main ways we can do that. One is through the practices that we take on that help us maintain a friendly relationship with reality, where we want to know what’s real, where we develop the virtue of humility; to not pretend we know more than we do. And where we really want to know what can be done, even if it’s painful.

And then I think there are social practices. We need to be listening to one another in ways that are respectful and reverential; to be able to say, “Hey, here’s what I’m worried about, do you think I’m missing something?” And in that, we create circles where we have more balance than we’d have just going on alone.

AT: This might be a silly question, but you often quote Lord of the Rings in Life After Doom, and I was wondering if those books influenced how you view our current struggle with climate change.

BM: Like a lot of people, I came across the Lord of the Rings books when I was a teenager, and they just sucked me into this alternative reality. I didn’t even understand why they were touching me so deeply; in fact, I found at points it was almost scary because they connected with me on some visceral level that I couldn’t put into words. And they stayed with me through my whole life.

As I was working on this book, I remembered Mount Doom, the geographic location that’s so central to Lord of the Rings, and it made me realize that in many ways, J.R.R. Tolkien was living with eyes open toward doom. He had, in his lifespan, seen the two worst world wars that the human species has ever faced. I went back and read a couple of the books to re-immerse myself in his struggle, and I felt deeply moved all over again. What Tolkien did is presented a kind of virtue. You see it in Sam and Frodo, but especially in Sam, who believes, in the words of Vaclav Havel, that some things are worth doing no matter how they turn out. And that, to me, is the great moral instinct that we need in these times. Some things are worth doing no matter how they turn out.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

***

Anne Thériault is a journalist in Kingston, Ont.

So where is God in all this?

What happened after God said “It is very good.”, and after He commanded us to have “dominion” over the earth? Man sinned and distorted creation. Romans 8:20-24

Is God not in control of all things? Did He leave it only up to us to solve our mess? (Not saying we shouldn’t try, but God must be in it or it will fail.) Proverbs 19:21 and James 4:13-15

I think the author has it wrong, People, including “Christians” today spend far more worrying about the immediate, than they do about their life after death. Matthew 6:19-34; John 16:33 and Romans 12:2