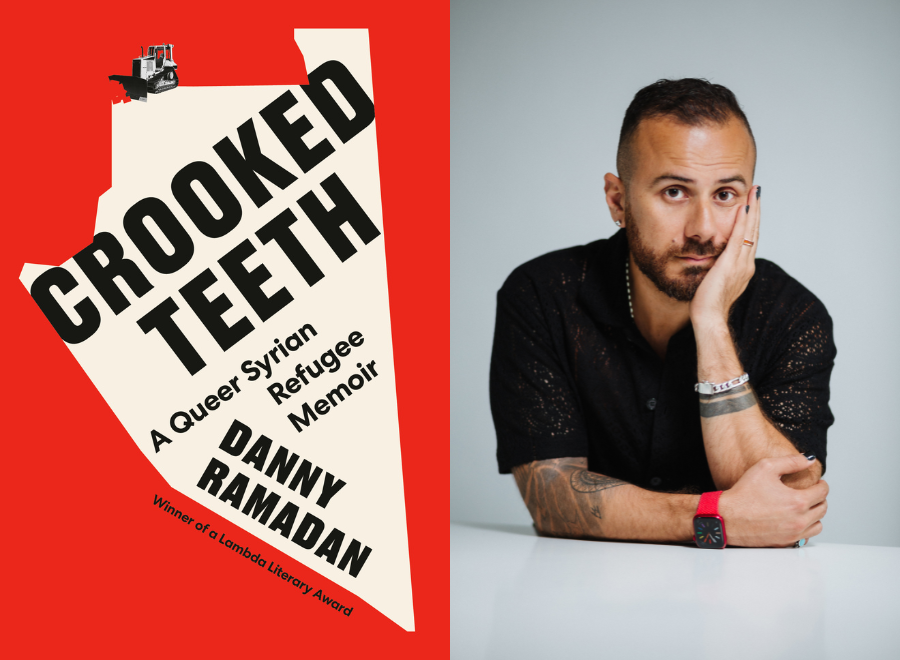

Danny Ramadan went from struggling with his queerness as a child to hosting a secret community group for 2SLGBTQ+ Syrians from his home as an adult. But his experiences were not linear, nor without hardship. Ramadan was born in Syria and worked as a journalist in Egypt during the Arab Spring protests, sometimes struggling to find work after his identity as a gay man was revealed. After his support group landed him in prison for six weeks, he fled to Lebanon before eventually coming to Canada as a refugee. Now based in Vancouver, Ramadan channels his energy towards helping 2SLGBTQ+ people find safe homes abroad. Ramadan’s annual fundraiser, An Evening in Damascus, has raised over $300,000 for queer refugees since he started it in 2015.

Ramadan has woven his life experiences into his award-winning works of fiction, The Clothesline Swing and The Foghorn Echoes, but now he’s ready to tell his story on his own terms. His new memoir, Crooked Teeth, is a candid look at his journey.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Sherlyn Assam spoke to Ramadan about growing up queer in the Middle East, the importance of community and the significance of his new book.

Sherlyn Assam: Did you know writing would change your life so drastically?

Danny Ramadan: I think I’ve known all along that there is something special about the power and circumstance I was born into. That sounds egotistical, but it comes from a place of naivete: I believed I would be able to take this talent — the only thing I had at one point — and turn it into something majestic.

SA: You went by your given name, Ahmed, when you started writing in Syria, but among the queer community, and in your present-day life, you’re known as Danny. Was it hard to divorce yourself from who you were expected to be and who you wanted to be?

DR: It felt like navigating two different personas and two different lives. That was the only way I could be both the writer I wanted to be and the human I wanted to exist as. It was more of an answer to an impossible equation. Being completely ‘out’ meant that there was no future for me as a writer, and being a [straight] writer meant I would not be able to answer to my desires, my calling and my queer identity — not just from the perspective of being attracted to other men, but also from the political view of what a queer person is.

Over the years, [Ahmed] Ramadan was the person who was taking all of those punches and taking all of those painful experiences. I wouldn’t say I divorced myself from him, but I think I consumed him. I took him in, I sat him down, I apologized to him repeatedly about all the bad things that happened to him. I wished him a good night’s sleep, I sang him a lullaby, and let him drift away. I think it was time for him to rest.

More on Broadview:

SA: How have your survival instincts changed since moving to Canada?

DR: The joke I always make is that I traded homophobia in the Middle East for racism in Canada.

When I came here, nobody told me that suddenly I will become a person of colour. I did not realize how fluid privilege is and how it changes. I was welcome to be part of the queer community as long as I was a coconut: brown on the outside and white on the inside. That didn’t ring as authentic to me. There was a big challenge in finding my own community because I did feel like I was disconnected. I had my own space back in Damascus where I was doing something for the community, for a sense of belonging, and the mainstream gay white community just didn’t speak to me that way.

SA: How did writing for both a Canadian and Syrian audience influence how much you were willing to share in your memoir?

DR: I believe I am a great storyteller, but I also believe in my right to choose my listener. We as storytellers always think of it as one active verb, but it’s an exchange. I wrote this book so that somebody who identifies within the mainstream community – a cis[gender], heterosexual man or woman who has a white racial identity – would see the boundaries I created for them. I wanted to be very clear in those boundaries: I’m not performing my trauma on a stage. That is not my goal. Instead, I wanted those readers to investigate how they see trauma, and I wanted to change why they want to read about it.

A person who is Syrian and comes from the same background as me, however, would be able to read this book and fill in the blanks. I don’t think every word in this book is meant for every reader.

SA: How do you process the pain of people who created an environment where you didn’t feel worthy of love?

DR: Do you ever? A couple of months ago I was having a conversation with my therapist and I was crying. I said, “I thought if I did this, I would let go of my sorrows.” My therapist looked me in the eye and replied, “Danny, you’re not supposed to ever let go of your sorrows.” I agree with that. Letting go of your sorrows is letting go of part of what makes you a complex, mature human being. There is a place where we have to stop judging sorrow negatively. Sorrow is part of the emotional dynamics that we have in our heads, similar to joy and happiness and pleasure. We don’t judge our joy, why should we judge our sorrow?

SA: You titled your memoir Crooked Teeth, but you’ve also identified those words as your trigger. What was it like working through that trauma on the page?

DR: I think I know how to navigate my trauma. I’m not afraid of it or of the hurt that it causes. I like the fact that I put it on the page. I feel like I’m holding it and taming it — like a banshee that was trying to eat me but instead, I managed to befriend it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

***

Sherlyn Assam is a Canadian freelance writer and editor based in the U.K.