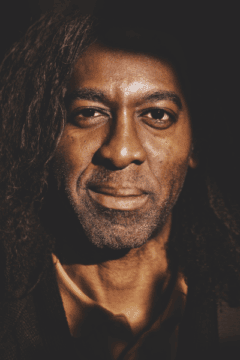

Ian Williams has been thinking a lot about how we talk to each other. In particular, the Giller Prize-winning author is worried that life in the digital world is making it more difficult to have challenging conversations, the kind where people can disagree but still listen to each other with empathy and respect.

Instead, Williams sees an increasing trend toward snarky ripostes and categorizing people as being on the right or wrong side of an issue, rather than trying to understand where they’re coming from.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

These concerns form the kernel of his recent book, What I Mean to Say: Remaking Conversation in our Time, written for 2024’s Massey Lectures — an annual lecture series by prolific Canadian thinkers that is broadcast on CBC radio and published by the House of Anansi Press.

Through this format, Williams explores various aspects of conversations: what makes up a good one, how we censor ourselves and what’s at risk when we lack deep, meaningful dialogue with others. Along the way, Williams as-narrator is aided by — and in conversation with — a fictional character named Edna, whose remarks appear as editor’s notes in the margins of the text.

Anne Thériault spoke to Williams in Toronto about what it takes to converse in today’s world.

ANNE THÉRIAULT: An interview is a strange kind of conversation. For one thing, there’s an imbalance of power, because I’ve read your book, so I know more about you than you do about me. And I have a list of questions, but you have no idea what I’m going to ask.

IAN WILLIAMS: And you could have some kind of strategy. You could do all of these things to make me look like an idiot. It’s a strange kind of beast, right? Also, you get all of the answers, but I never get a chance to ask you questions. I can’t ask you to tell me about your life. So it’s a bit like being on trial.

AT: Why did you want to write about conversations?

IW: I like to use non-fiction as a way to work out my ideas about things. So for me, the best attitude to come to a non-fiction project with is confusion or doubt or uncertainty. I have so many issues around this time that we’re in, and “conversations” provided this umbrella under which I could talk about loneliness, friendship, companionship, isolation, the media, polarization and so on. And all these things fit under “how people interact on social media.” Why are we talking to each other like this now?

AT: In What I Mean to Say, there are points where it’s clear you’re frustrated with how we talk to each other, points where you’re bordering on being sort of cynical and then points where you’re quite vulnerable about how it impacts you.

IW: Non-fiction tends to be this argument-driven thing. Like, “Here are my points; here’s the evidence. I’m going to line this all up for you, and you will be persuaded by the end of it.” But I wanted to make something a lot more discursive, so I will fight with myself, sometimes in the form of Edna talking back, and take many sides. I think the best books have a kind of emotional range to them.

AT: Sometimes Edna’s like your conscience or fact-checker. For example, you write about the apparent joy in viral videos of someone turning on their cochlear implant for the first time, and Edna replies that, in fact, there is a lot of contention about those videos in the Deaf community. Why did you decide to include that character?

IW: Edna is this amalgamation of notes and editorial response from my editors — and then some of the snarky stuff is me. It’s that voice in our heads that’s always a little bit critical. I was getting all of this really good feedback from my editors, and I incorporated some of it into the text. But then I thought, no, actually, folks should get to participate. Editors do so much work, and then they get erased behind the author. They make a valid point, and I don’t need to digest it. I just need to present it, right?

And so Edna is a way to hold contradiction in a space that doesn’t destroy the fabric of the book. She’s not always disagreeing. Sometimes she’ll elaborate and say something that I don’t know. I think that to create space for another impulse within a text is important. So the text will work against itself. It has its own formal tension.

AT: Do you think there’s ever been a technology that has impacted the way we talk to each other as much as social media has? For example, when the printing press was invented, people began attacking each other’s opinions through pamphlets. At that time, was there a similar concern about this breakdown in how people talked to each other?

IW: No, I don’t think there has ever been a revolution in communication like this moment. In some senses, we’re really fortunate to be born in this moment — both to see it happen, and also to realize that at some point we will be the last generation that knew a time before computers and social media.

In 40 years, we’ll be like, “Once upon a time, you couldn’t ask AI questions; there were paper maps.” We’ll become guardians of another time that people in the future will only know theoretically. We’ll know what it is to be lost and to have a conversation face to face, rather than behind screens. But the simple answer to that question is, no, I don’t think we’ve seen anything like it.

More on Broadview:

AT: I don’t necessarily think that social media is good, but I also think we have to learn to live with it, because it’s not going away.

IW: No, it’s here permanently. And just like how we speak differently to our moms versus how we speak to our best friends versus how we speak in the workplace, I think we’re going to have to construct various selves around social media — here’s my online self, and here’s my in-person self. It’ll be another identity that we have to manage.

AT: In the lectures, you ask your friends if they remember their child’s first words and juxtapose it with how some people lose language — through colonization or medical events or others silencing them. It reminded me of when my son was 11 months old. We started asking him, “Where’s the light?” and “Where’s your bed?” and he would point to what we named — he knew these words without us realizing it.

IW: A lot of folks I talked to were surprised by how much their kid knew. I feel like this must be kind of true more generally — we would probably be surprised by how much other people hold. Living in our own bodies, we tend to think, “Oh, my perspective is somehow unique.” But other people have so much to offer and so much to bring. We need to assume that folks are smarter than we think they are and listening to us more than we think they are, even if they’re not expressing it. Even people that we see as being on the “other side” from us.

AT: So much of that goes back to having uncomfortable conversations, with, for example, people we disagree with politically, rather than barbed social media interactions. As you write in What I Mean to Say, it can be helpful in those difficult conversations to try to set aside our own convictions and really experience the other person’s perspective without trying to persuade them over to our side.

IW: I work at a university. I’m a Black man. My politics are pretty obvious. But I still didn’t want to be like this champion of the left or champion of the right, criticizing the left or criticizing the right. The problems of conversation in our age affect both sides. They’re cancelling on the left as they’re cancelling on the right. They’re banning certain things on the left as they are banning on the right.

So, yeah, we should have convictions, and they should probably tilt us in one direction or the other, but we shouldn’t be so righteous to think that our side has the monopoly on morality. We don’t want to have to be in those politically uncomfortable conversations. But we also need to have them. They make us realize, oh, this person is not a jerk. But when we spend all of this effort trying to pull them over to our side, then we lose out on the other aspects of them, because then they become defensive, and we don’t like that person.

When you’re really clenched and defensive, it’s not your best self. We need to have less of an agenda and fewer scripts [when it comes to social interactions], and then let ourselves have the hard conversations that way.

***

This article first appeared in Broadview’s July/August 2025 issue with the title “Hard Conversations.”

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Anne Thériault is a journalist in Kingston, Ont.

The Christian church is beginning to recognize the need to treat each other with respect in listening as the church dies. Some churches now have coffee tables set up for people during Worship. Some go so far as to have dialogue amongst the table groups in place of the “message”. I don’t know how many once strong churches ar shifting from ‘I’m right & I love you as Christ taught if you believe as I do”.

As I serve as Pulpit Supply, I find myself in churches that have split over- ” you must believe as I believe & talk as I talk”. I was fired in one church in a 3 Sunday engagement over a key element of change in honesty that is needed.