Theland Kicknosway was only 16 when he posted his first TikTok video in 2020. Today, the Potawatomi and Cree youth advocate has over 430,000 followers on his account @the_landk. He often shares teachings about his culture or videos of himself dancing, transforming from street clothes into powwow regalia in the blink of an eye. In a viral video from early in the pandemic, he braids his hair while encouraging Indigenous boys and men to wear theirs without shame. “Our power is in our braids, so let’s show them proudly,” he says.

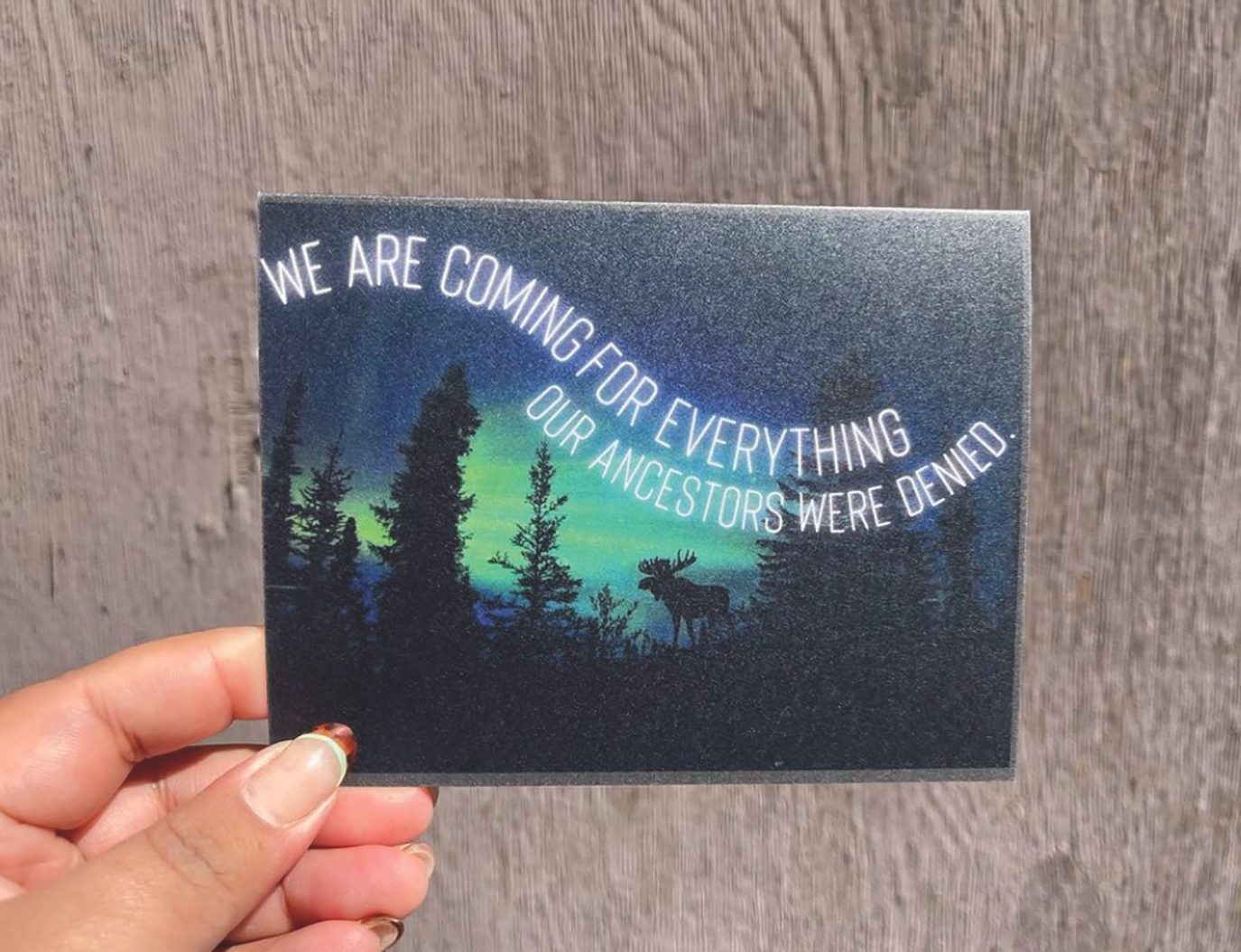

Another TikToker, Inuk throat singer and songwriter Brenda Montana (@inuksuk), shares everyday glimpses of her experience up north with her over 120,000 followers. Over on Instagram, Amy Jackson, the Opaskwayak Cree founder of @nativelovenotes, not only spins “unapologetically Rezzy” humour into digital designs, but then turns them into goods like shirts and stickers and has even launched a physical store in Winnipeg.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Creators like Kicknosway, Montana and Jackson are part of a young generation of Indigenous social media stars who are using their platforms to celebrate their cultures and push back against negative stereotypes. Through the content they post online, Indigenous people can define Indigeneity and identity, while allowing non-Indigenous people the chance to bear witness and learn. Other gaps are closing too. The divide between rural and urban presence online is being erased as Indigenous communities connect to the internet via satellites on their smartphones. And with people of all ages using social media platforms, it makes me feel like many generations of us can learn to understand the others’ experiences. Young people bring knowledge of evolving technologies to the table, while Elders and community leaders bring lifetimes of wisdom about culture, language and tradition.

One thing that bonds Indigenous people online is memes. Since their rise in popularity in the mid-1990s, memes have become a part of online culture. You have seen different types of them, whether they be rude, absurd, inspirational, surreal, hilarious or confusing. Memes use visuals, often with superimposed text, to create the modern-day equivalent of a political cartoon. Remixing or parodying popular culture and ideas, they are shared across the Internet and can go viral.

In the hands of Indigenous creators, memes have become a way to share community and connection, often in the form of in-jokes. These memes tackle a broad range of issues, from life on reserves to pipelines and missing and murdered Indigenous women. Memes are a way to support and recognize LGBTQ+ and Two-Spirited people and issues. We can take jabs at politicians, as well as our own chiefs and band councils. We can playfully tease aunties and uncles. When we share candid memes that address the reality of our lives in the margins, this sense of humour can be “deadly”: razor sharp, sometimes bizarre and usually hilarious.

Arnell Tailfeathers is a Niitsitapi visual artist and meme creator. In a 2018 CBC article, he explained: “I began thinking what I could do with [memes] in terms of decolonization and what’s happening in Canada right now…Some people are doing comforting stuff to make you feel good, but then other people are doing deep political things with it.”

View this post on Instagram

With over 43,000 followers, Decolonial Meme Queens is an Instagram account aimed at an Indigenous audience. Many of its postings play on the failures of Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples: in one meme, a woman squints into the distance under the tagline “looking for the truth in all this reconciliation™.️” Run by a collective of women and Two-Spirit creators, Decolonial Meme Queens is a place where we can feel validated, where our trauma as Indigenous people is acknowledged and centred.

More on Broadview:

- I returned to the land of my Sámi ancestors to reclaim my identity

- How I have found healing in remembering sacred Indigenous teachings

- This Indigenous entrepreneur wasn’t dissuaded by 170 funders saying ‘no’

The account also shares information about actions one can take beyond social media. “Land Back” and “Water Is Life” are phrases brought forward by Indigenous meme creators to instigate dialogue about our rights to land and water. In the words of the Decolonial Meme Queens, “Memes will not decolonize you, but actively dismantling the system of colonialism will.”

Johnnie Jae, the founder of A Tribe Called Geek, a media platform focused on Indigenous STEM and geek culture, was enthusiastic about Indigenous people “claiming” Grogu, popularly known as Baby Yoda, a Star Wars character introduced in the TV series The Mandalorian in 2019. In the show, Baby Yoda, one of the last members of his species, is being pursued by people who would like to kill him or exploit and steal his knowledge and power.

“We see a lot of those same struggles within our own communities,” Jae said in a 2020 CBC story. “Native children have been targeted and trafficked by for-profit adoption industries, been adopted out to non-Native families, and that really severs that connection to who we are as Indigenous people.”

Baby Yoda was quickly embraced by Indigenous pop culture, and many of us felt a kinship with the character. Beadwork, clothing and memes celebrating the lovable alien exploded across Indian country, brightening everyone’s day.

The gap that is being bridged is the transmission of culture in a digital age. People are presenting their Indigenous identity to others and in doing so are being affirmed.

As a big fan of a good laugh, I sincerely applaud the creators whose work reminds us that if you say the word “reconciliation” into a mirror five times, Justin Trudeau appears to do a land acknowledgment.

***

Mike Alexander is an Anishinaabe writer and artist from Swan Lake First Nation in Manitoba, now living in Vancouver.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s September 2022 issue with the title “Going viral.”