Justine Abigail Yu is all too familiar with the experience of living in between cultures. “I feel like I have two feet in two different places all of the time,” says the founder of Living Hyphen, a community that showcases and supports the storytelling of Canadians with hyphenated identities.

Yu was born in Manila, Philippines, and when she was four, her family moved to Scarborough in east Toronto. Growing up, she had to navigate what it meant to be a Filipina-Canadian when she identified with neither the mainstream media’s Filipino stereotypes nor its overwhelmingly white representations of Canadianness.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

But it wasn’t until 2015 that Yu realized just how white the Canadian mediascape was. That fall, she attended a panel discussion at the Feminist Art Conference in Toronto where writers of colour recounted their challenges in the Canadian publishing industry. She was struck by the stories they shared. Writers had encountered ethnicity quotas at publishing companies and been pigeonholed into cultural archetypes. A Japanese novelist had been told by an editor that her story wasn’t Japanese enough.

More on Broadview:

- In ‘Shadow Life,’ an Asian elder isn’t a victim. She’s the hero.

- How new Black art initiatives are changing the game for overlooked artists

- Zarqa Nawaz wants to tackle romantic tropes about Muslims in upcoming series

As a writer who still feels strongly tied to her Filipina roots, Yu realized that she might face these barriers in the future. The moment inspired her to found a community for storytellers like her, who were part of diasporas or had been displaced.

“I wanted to build my own house,” Yu says. “I didn’t want to wait for somebody to let me in and then tell me that my story is not good enough.”

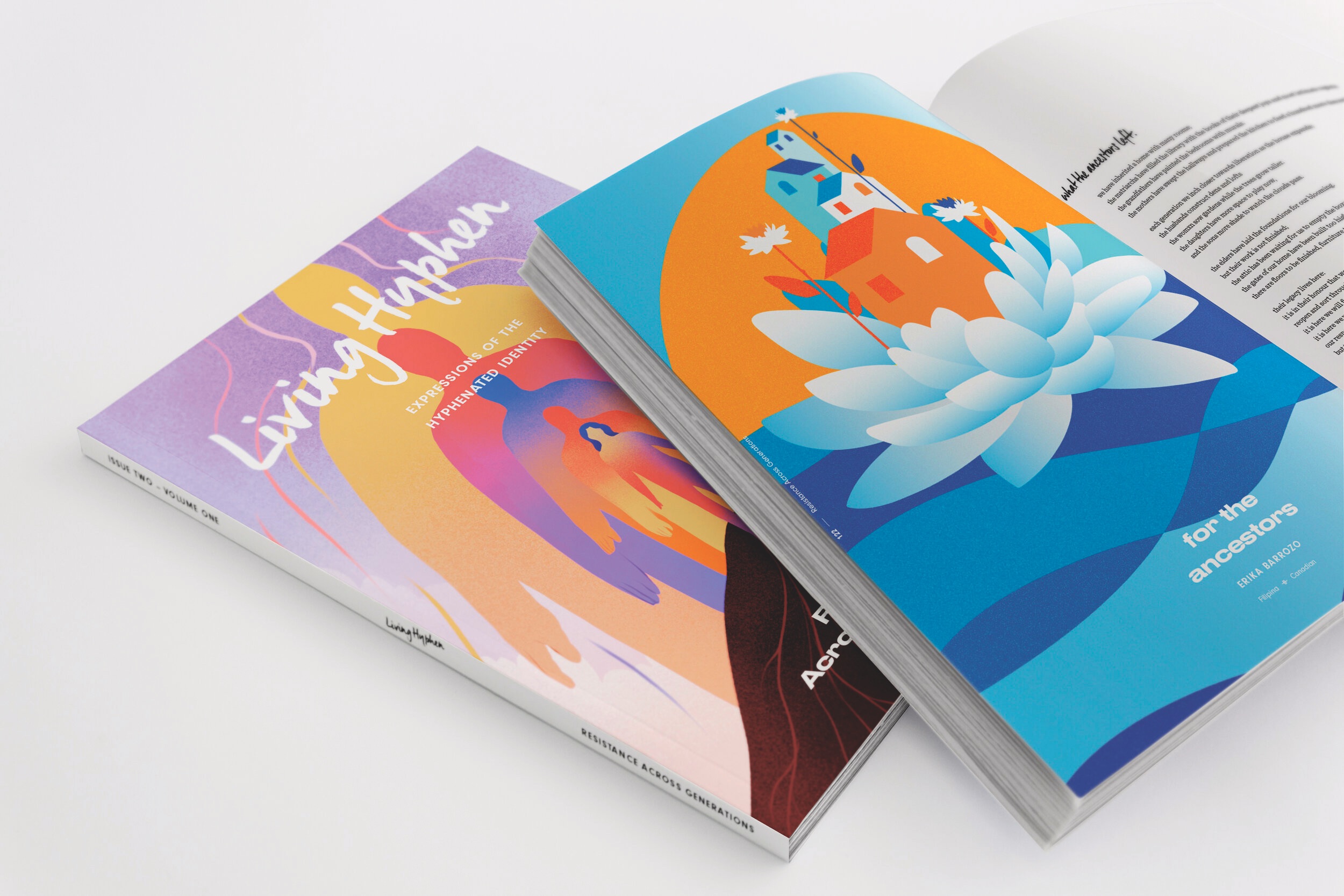

Living Hyphen launched as a print magazine in 2018. When the call for submissions was released, over 200 pieces poured in from across Canada, representing a wide range of ethnic backgrounds, religions and Indigenous nations. The first printing of 500 copies sold out in less than a month. To Yu, the demand showed that hyphenated people were hungry to tell their stories and see themselves reflected in texts. But she also became aware that many others were afraid to share their stories — “the influences and institutions around us have told us that they don’t matter,” Yu says. So Living Hyphen expanded to include cultural programming, including storytelling nights at cafés and bookshops, as well as writing workshops that cultivate hyphenated Canadians’ confidence in their stories.

Living Hyphen has continued to grow, and its second magazine issue, released in mid-July, received over 700 submissions. Yu couldn’t print all of those stories, but she still wanted them to be told. Podcasting “seemed like a natural next step,” she says. The first season of the Living Hyphen podcast launched in May, and invited hyphenated storytellers to explore the theme of “homestuck”: “whatever home might be, whatever one’s relationship to their home(s) might be, and whatever being stuck can mean,” the show description explains.

Yu was inspired by the parallels she had observed between hyphenated Canadians’ experiences and how the COVID-19 pandemic pushed people to connect with their loved ones in creative ways. “I think everyone’s getting a glimpse of the experience of being far from where our families are from, under circumstances that we cannot control,” she says. When her family first moved to Canada, her parents strived to stay connected to home, but technology wasn’t what it is now. They used prepaid phone scratch cards. “It would be, like, 20 numbers to dial,” Yu recalls. “Sometimes it didn’t work, and you didn’t know if the person in the Philippines would actually pick up — and so you missed them.”

Moving into audio has lent these stories a new intimacy and resonance. Yu points out that many hyphenated Canadians are “people who have had to move,” and often their stories have been passed down via the oral tradition rather than being archived in written documents. It’s such a precious thing, then, to be able to record and archive stories told in their own voices.

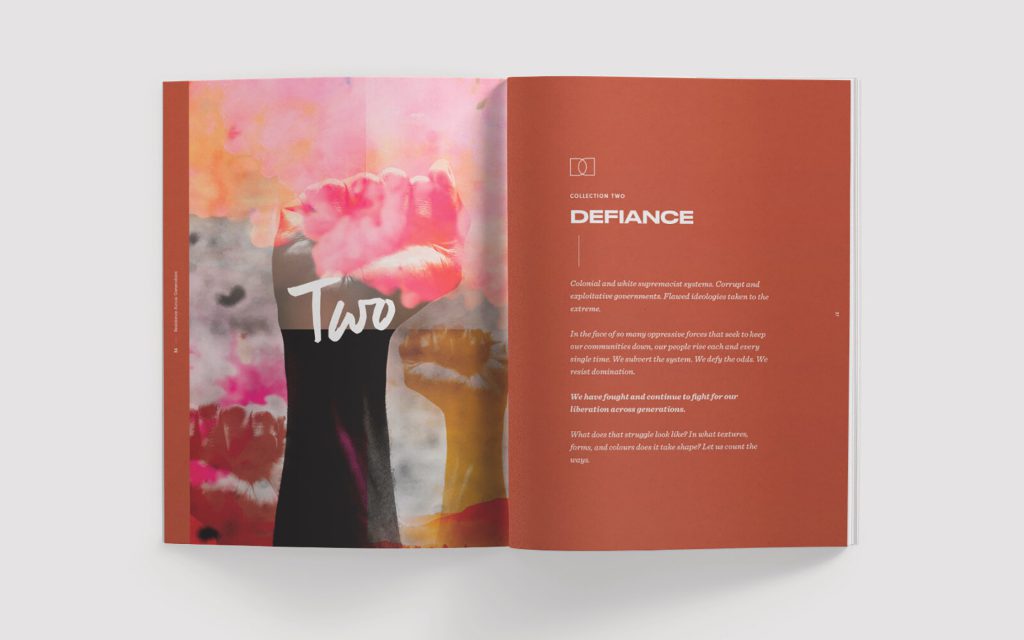

But Yu emphasizes that Living Hyphen isn’t just a storytelling community — it also strives to work in solidarity across racial lines. Since launching, it has heightened its focus on advocacy, including Indigenous allyship and anti-racism. The first volume of Issue 2, Resistance Across Generations, takes on systems of oppression like white supremacy and western imperialism. It highlights stories of survival, defiance, triumph and legacy from 60 writers and artists, including poetry by Vietnamese-Chinese-Canadian Dona La Luna and illustrations by Colombian-Canadian Marcia Diaz.

“We can’t be a community that talks about migration, home and identity without acknowledging that so many of us are immigrant settlers who have benefited from colonial violence,” Yu says. She adds that many in the community hail from homelands that have also experienced colonial violence. “Living Hyphen has always been political.”

***

Jadine Ngan was a summer 2021 intern at Broadview.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s September 2021 issue with the title ‘I wanted to build my own house.’