On the afternoon of Jan. 11, 2007, Capt. Brian Weeden was on duty at a U.S. Air Force complex located deep inside Cheyenne Mountain, near Colorado Springs, Colo. The complex is the terminus for a vast flow of information on activity in space: if a rocket is launched somewhere or a satellite circles in orbit, the Cheyenne Mountain watchers know about it. Among the hundreds of spacecraft on their radar that day 13 years ago was a Chinese weather satellite called Fengyun-1C. It had been launched in 1999 but was now derelict, loitering about 860 kilometres above Earth.

Twelve thousand kilometres away, at the Xichang Satellite Launch Centre in China’s Sichuan province, a ballistic missile roared into the night sky. Atop the rocket was a 600-kilogram device that can aptly be described as a high-tech battering ram. Arcing upwards, the missile accelerated through Earth’s atmosphere and into the emptiness of space, its guidance system pointing it on a collision course with the Fengyun-1C satellite.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

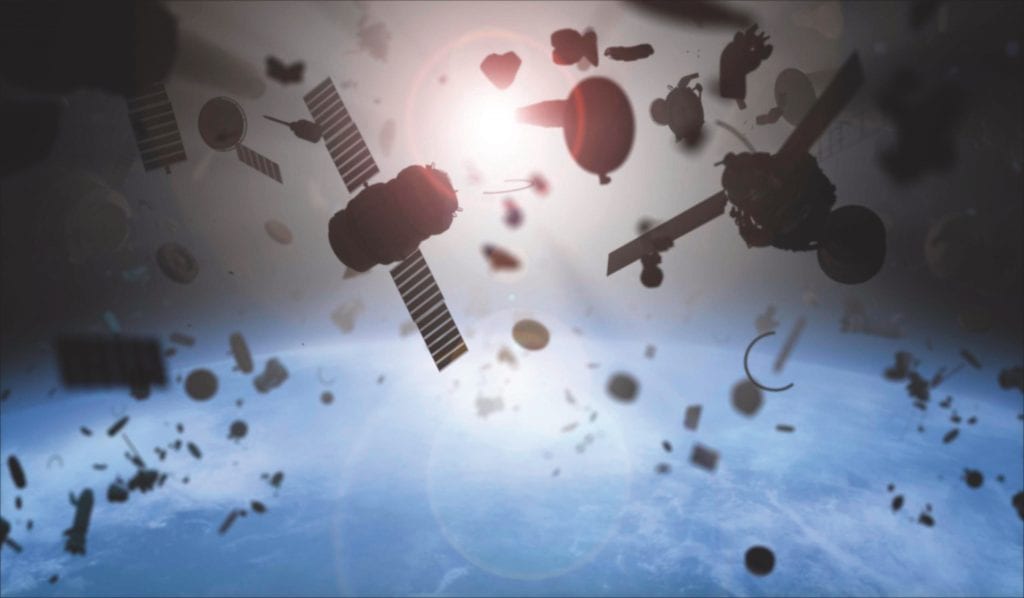

Engineers from the U.S. space agency NASA later calculated that the projectile the missile carried — known in space jargon as a “kinetic kill vehicle” — slammed into the satellite at a speed of 32,400 kilometres per hour, shattering it into thousands of pieces that remain in orbit today.

Watching the episode unfold, crews inside Cheyenne Mountain realized instantly that China had just successfully tested an anti-satellite weapon. Weeden, now the director of program planning for a space-security think tank in Washington, D.C., remembers the stunned atmosphere in the bunker: “There was a kind of silence, a kind of, ‘Holy crap, the crazy bastards did it.’”

Spacefaring nations have prized the military high ground of Earth’s orbit since the dawn of the space age more than 60 years ago. Until the Chinese test, military activity in space had been largely dominated by the Soviet Union (and later Russia) and the United States. Both had built space-based systems for reconnaissance, communication and munitions guidance into their capacity to wage war. Both had tested weapons designed to destroy the other’s satellites. But the certainty of mutual destruction in a war on Earth came to temper their behaviour in space. Since the mid-1980s, the superpowers had observed an informal moratorium on the testing of anti-satellite weapons.

The test Weeden and his colleagues witnessed that day in 2007 not only blew a dormant weather satellite to bits; flexing its new muscle as a superpower, China shattered the equilibrium that had secured a fragile peace in space for nearly 30 years. China’s anti-satellite program is a key factor behind the seismic shift in doctrine that led to the newly minted U.S. Space Force, tasked with conducting American military operations in space. The most powerful military in the world now officially considers space a “warfighting domain” like the land, sea and air.

Weeden contends the U.S. move merely formalizes what has been evolving unofficially for the past 20 years. And he points out that the United States isn’t the only player. China and Russia operate their own space forces; both are developing a new generation of anti-satellite systems. France is establishing a space command and plans to build satellites able to destroy other spacecraft. Japan launched a space force this year and is considering an anti-satellite system. India successfully tested an anti-satellite weapon last year and has created a new organization to co-ordinate space-related military activities.

History shows that arms races seldom end well. The naval buildup before the First World War is one obvious example. The weaponization of space translates into increased odds of war in space. “When the leading space power takes that kind of stance, the other space-faring nations will take countermeasures,” says Paul Meyer, a former Canadian ambassador to the United Nations and a space-security specialist at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, B.C. “You start to get into contingency plans for conflict…and you could, in a crisis, spark something that could be devastating.”

One evening last winter, I drove through the snow to a suburban multiplex to watch Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, the final episode in a trio of trilogies that began in 1977. It wasn’t much of a movie — more a rehash of the clichés tens of millions of moviegoers have come to expect from the multibillion-dollar Star Wars franchise.

About halfway through the film, however, the penny dropped: in the same way that cowboy movies encouraged warped stereotypes of the West, Star Wars and its many imitators have entrenched a skewed version of space in popular consciousness. We like to imagine it as a place of constant conflict where battles over earthly compulsions like power, greed and revenge play out on a galactic scale. Aside from a select few, no one has any actual experience of space, so the fantasy version has become the default.

The Rise of Skywalker premiered in Canadian theatres on Dec. 19 last year. In almost perfect serendipity, the U.S. Space Force officially launched just a day later. Before long, the serious aspects of the Space Force story gave way to snickering about the service’s logo, which looks like a Star Trek knock-off. Call it the Star Wars syndrome: the penchant of the media and general public to shrug off events in space as less real than events on Earth. Meyer and others in the space-security community struggle against it constantly. “The cultural context for taking space seriously has been coloured and compromised by Hollywood,” says Meyer. “You can’t get the media — mainstream or social — to take the subject matter seriously without referring to Star Wars or whatever the current science-fiction fantasy is. It renders it as an amusing aside rather than something of real importance.” As if to underscore Meyer’s point, Netflix recently debuted a new sitcom starring funnyman Steve Carell. Its title: Space Force.

As remote and unreal as space may seem, the distance between space and Earth has been shrinking steadily since the launch of the first Sputnik in 1957. Today, satellites are so entwined with everyday life — from ATMs to mobile phones to farmers checking on their fields — as to be virtually unnoticeable. With the advent of smaller satellites that can be launched in the dozens by a single rocket, Earth will be even more tethered to space in the years to come. “We are dealing with an environment that has, in the past couple of years, seen an exponential growth in activity,” says Meyer, “with projections over the next six to 10 years increasing by a factor of 10 the number of active satellites — from roughly 2,000 now to something like 20,000.”

The more things that satellites do, and the more satellites that do them, the greater the stakes should they become targets in a conflict. A 2018 book called War in Space paints a chilling picture of the catastrophe that could result. Author Linda Dawson, a former NASA engineer and a retired lecturer at the University of Washington, leads readers on a tour of what a major disruption of satellite networks might look like. At first, it may just seem like a glitch: cellphones go silent, ATM cards stop working, auto-mobile navigation systems quit. The hiccup becomes a full-fledged crisis as the disruption affects the complex constellations of satellites that make up the U.S. Global Positioning System (GPS) and its international counterparts. Personal computers go haywire. The internet goes dark. Power grids sputter. Pilots can’t find runways. Transportation networks shut down. Food shortages loom. Life, as a lot of us have come to know it, grinds to a halt. The scale of disruption would make the COVID-19 crisis seem like a mere inconvenience. “I do not think the average person is aware of these dangers,” says Dawson.

More on Broadview:

- A recovery worker on the hard realities of disaster and healing

- 50 years after Apollo 11, we’re still fighting over the moon

- My dad was deported after 23 years in Canada. We fear my mom is next.

Small-scale previews of what Dawson imagines have actually occurred. In 2016, U.S. Air Force GPS satellites that also serve civilians fell out of sync. The incident affected police, fire and EMS radio equipment in the United States and Canada, and the British Broadcasting Corporation’s digital radio service. Last year, the European Union’s version of GPS went offline for a week. About 100 million mobile devices would have failed if they hadn’t automatically connected with other systems. Both events caused a stir in military and tech circles, but barely a ripple in the public at large.

In the spring of 2019, Jessica West journeyed to New Delhi to speak at a conference on space security. West is the space-security specialist at Project Ploughshares, a peace research institute connected to the Canadian Council of Churches. Before the conference, West and some of the other participants took part in a crisis-simulation exercise in the offices of a prominent Indian think tank. The idea was to role-play a regional emergency — in this case, sparked by an anti-satellite test, a terrorist attack and suspected ground-force incursions — and study how it might escalate.

The simulated crisis peaked with an airstrike on nuclear facilities. Cyberattacks targeted satellites linked to military action on the ground, but “there was a resistance to engaging in kinetic warfare in outer space,” West says. Still, she adds, “it was clear how important outer space was to the conduct of operations on the ground.”

The 1991 Gulf War, when an American-led coalition drove Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi forces out of Kuwait, is sometimes called the “first space war,” not because fighting took place in space but because of the critical role GPS and other satellites played in military operations. In the years since, satellites have become as intrinsic to the world’s armed forces as they have to life for civilians.

West directed the research team for the 2019 edition of the Space Security Index, an exhaustive annual report on developments related to safety, security and sustainability in outer space. According to the report, in 2018 the United States, Russia and China had a combined total of 263 dedicated military satellites in orbit, in addition to operating several dozen GPS (or equivalent) satellite systems. Eighteen other countries, including Canada, operate military satellites of their own or piggyback military functions on top of civilian uses.

“There’s always been this fear of war in space, as distinct from war on Earth,” says Brian Weeden, who contributed a chapter to the report. “It’s not [distinct]. It’s the integration of space into terrestrial warfare, not something that happens separately.”

Within that integration lurks the trigger for a kind of conflict never seen before — where events on Earth spark a clash in space, or where events in space incite hostilities on Earth, with unpredictable consequences up to and including a nuclear exchange. “The most likely way to initiate a conflict would be one country disabling a satellite or spacecraft of another country,” says Dawson. “Depending on the result, the conflict could escalate into further destruction in orbit or the beginning of more traditional warfare back on Earth.”

Using projectiles to smash enemy satellites would create vast fields of space debris that could imperil other satellites, including those belonging to the attacker, and set in motion an escalating chain of collisions that could ultimately render orbit unusable. For that reason, cyberwarfare — the electronic jamming, hijacking or “spoofing” of enemy satellites so they send misleading signals back to Earth — is the most likely form that a conflict in space would take. (In fact, the Space Security Index reports that cyberattacks have already taken place in the Middle East and Ukraine, and during 2018 NATO exercises in Finland and Norway.) The arsenals of the major space powers are also believed to include lasers and other directed-energy weapons, as well as stalker satellites that can manoeuvre alongside an enemy spacecraft to spy on it or disable it.

In 2016, the Secure World Foundation organized a tabletop exercise similar to the one West took part in. The object, says Weeden, was to gain insights into how to prevent a crisis involving space assets from escalating into an all-out conflict. The confusion that reigned during the simulation was sobering. “One of the big take-aways was that a very sophisticated group of space experts found it very difficult to make good decisions and under-stand what was going on,” says Weeden. “If these people are struggling with this stuff, what is it going to look like for governments where people are generally not experts?”

During the early years of the Cold War, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists devised a symbolic doomsday clock to warn about existential dangers facing humanity: the closer to midnight, the greater the peril. I asked Paul Meyer where he would place the minute hand if such a clock existed for the threat of war in space today. “I’d put it at two minutes,” he said. “The trends are increasingly negative.”

Meyer has spent most of his working life focused on international security issues, including nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament. More recently, his emphasis has shifted to space and cybersecurity. The declaration by the United States that space is a warfighting domain rankles this career peacemaker. “Why the hell would you want to describe it as a warfighting domain unless you intended to fight a war there?” he asks. “How provocative is that to your potential adversaries?”

For Dawson, shifts in military doctrine combined with the developments of new weapons and technology add up to one inescapable conclusion: “I think a conflict in space is inevitable,” she says. She’s not alone. High-ranking politicians and military officials have long argued that war in space is a foregone conclusion. And the Woomera Manual, a major academic effort to clarify international law around military operations in space, assumes that conflict is a matter of when, not if.

Spearheaded by universities in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States, the Woomera project evolved out of another international effort based at McGill University in Montreal, aimed at developing rules for peacetime military activity in space. The Manual on International Law Applicable to Military Uses of Outer Space (MILAMOS) Project began in 2016 but hit a wall over the issue of inevitability. “It was a major ideological split,” says David Kuan-Wei Chen, executive director of McGill’s Centre for Research in Air and Space Law. The differences were so profound that the war-is-inevitable faction left after 18 months and started the Woomera Manual.

The MILAMOS Project includes international experts drawn from a wide range of relevant fields. “We don’t rule out [war in space],” says Chen. “There’s always that potential. We’re not idealists or dreamers.” But the project is rooted in the conviction that diplomacy and the rule of law can prevent tensions from escalating into conflict. “The purpose of what we’re doing is to make sure we don’t get to that stage,” he says, “to clarify the law in relation to the use of satellites, in relation to the launch of missiles and so on, so that states know exactly what the law is — what is permissible and what is forbidden.”

In 1967, a landmark international treaty declared outer space a global commons — belonging to all of humanity — and banned weapons of mass destruction. But the agreement did not prohibit the military use of spy or communication satellites or even space-based conventional weapons. And it did not provide for follow-up negotiations that could address more recent developments such as electronic jamming and spoofing. Much of the research being done by MILAMOS, the Woomera project and other initiatives, including ongoing UN talks, focuses on interpreting the treaty’s loose ends.

Chen, for one, believes the main thrust of the treaty — requiring states to consider the interests of other states in their space activities — is sufficient to address contemporary realities; one state destroying or disabling another’s satellites would not show due regard for the other’s interests. The devil, of course, is in the details. Chen cites one example: “To what extent is the jamming of a space object an act of war or tantamount to a threat of the use of force? This is what we’re trying to clarify.”

The accidental collision of an American communications satellite and an inactive Russian military satellite over Siberia in 2009 is the stuff of nightmares for Chen and others in the space-security community. It was bad enough that the crash flung more than 2,000 pieces of debris into space lanes already cluttered with junk. But what if the Russian satellite had been operational? What if the accident had occurred in a time of heightened tension between the two superpowers?

The dangers lurking today in space ought to send a chill through civilians. But the storm seems to be gathering largely out of sight and mind.

It took clashes like the Cuban Missile Crisis to galvanize public opinion against the testing and stockpiling of nuclear weapons in the 1950s and ’60s, leading to treaties that moderated the threat. The dangers lurking today in space ought to send a chill through civilian populations everywhere. But as long as cellphones work and GPS devices get people where they want to go, the storm seems to be gathering largely out of sight and mind.

Pessimists like author Linda Dawson believe it will take a scare to shake public indifference, and that it’s coming. But there’s no guarantee the events that trigger scares can be contained. No one has ever managed a crisis in space before or negotiated their way out of one. As Brian Weeden puts it, “I hope it’s a scare and not a mourning.”

Oddly, a better understanding of the way things work on Earth may offer the best hope for securing peace in space. The climate crisis has driven home the connection between human activity and the health of the planet. This heightened awareness can also be brought to bear on the health of the environment above Earth. “We need to expand on our definition of what ‘environment’ means, to include space,” says Chen. “Any disruption or degradation of the space environment would have an impact on our way of life.”

Securing peace in space means unshackling ourselves from fantasy. It means acknowledging our connection to space every time we use a bank machine or message a friend. It means insisting that the interests of one nation should not prevail over the interests of any other. Really, it boils down to grasping that our well-being on Earth depends on the well-being of space.

It’s not rocket science.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s November 2020 issue with the title “High stakes.”

David Wilson is a writer in Toronto.

We hope you found this Broadview article engaging.

Our team is working hard to bring you more independent, award-winning journalism. But Broadview is a nonprofit and these are tough times for magazines. Please consider supporting our work. There are a number of ways to do so:

- Subscribe to our magazine and you’ll receive intelligent, timely stories and perspectives delivered to your home 10 times a year.

- Donate to our Friends Fund.

- Give the gift of Broadview to someone special in your life and make a difference!

Thank you for being such wonderful readers.

Jocelyn Bell

Editor/Publisher