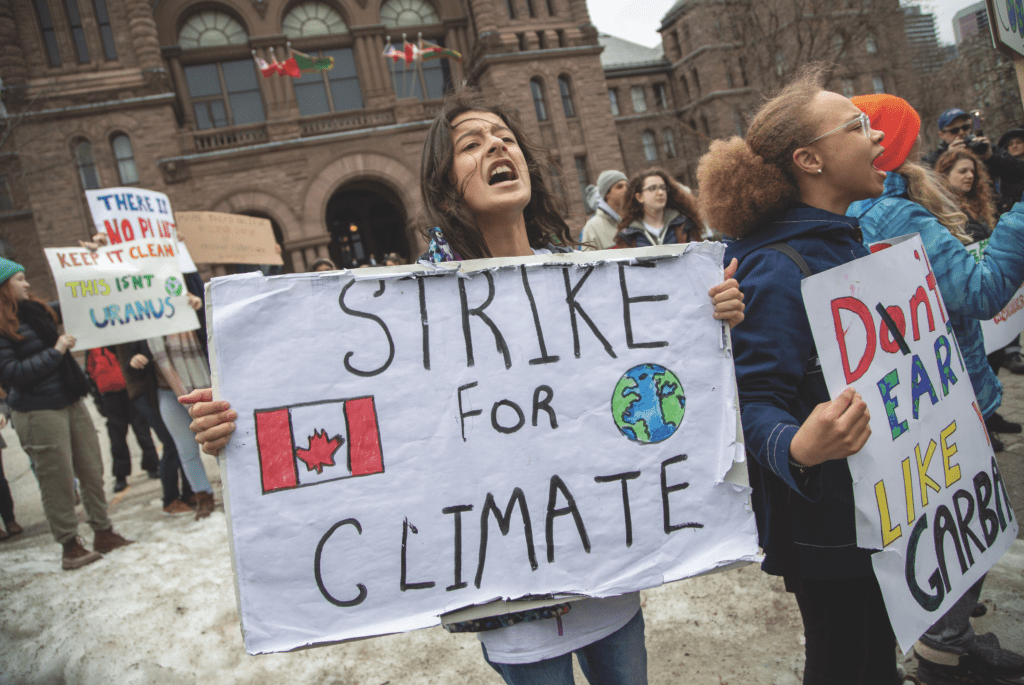

At the last moment before I leave, I put on my Bob Dylan T-shirt, a baby boomer’s gesture of revolutionary solidarity. I find myself eyeing people on the subway, sizing them up, searching for homemade banners or signs. Are they, too, heading to the climate strike at the Ontario legislature on this fateful Ides of March, one of the thousands of demonstrations in scores of countries planned for this day by the world’s young?

I feel that frisson of excitement. The sense of a grand gathering of human consciousness across time and geography. The suspicion that something momentous is on the horizon. I am a journalist covering the event, trying to understand who is behind the movement and what they want. But just showing up is reawakening my impulse to protest in public against injustice. I haven’t succumbed to that urge in decades, opting instead to warn people about what is happening to our planet through the written and spoken word. During those decades, the load of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere had climbed remorselessly, spawning floods, storms, hurricanes and fires of operatic proportion.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

And now the critical moment of action has arrived, driven by two sharply defined catalysts. The first was the Swedish student Greta Thunberg. In August 2018, then 15, she began staging her own school strikes, saying Sweden would need to step up its efforts to cut carbon dioxide emissions if it is to do its part to stop the global temperature rise from reaching 2 C.

With her pigtails, her bluntness — she has selective mutism, obsessive compulsive disorder and an autism spectrum disorder — and her unsparing ability to face the truth of our planet’s distress, she’s become a global inspiration. She’s so famous that she’s known to her followers exclusively by a single name, like the singers Beyoncé and Drake.

In November, she gave a TEDx talk in Stockholm that has been viewed more than two million times and translated into 30 languages. In recent months, Thunberg, now 16, has travelled — by train, which is low-carbon — to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, to the international climate talks in Poland and to the European Parliament, publicly admonishing the planet’s wealthy, its policy-makers and its politicians. They were, she accused, fiddling while the planet burns.

“The adults have failed us,” she wrote in the Guardian in late November. “[W]e must take action into our own hands, starting today.”

The second jolt was a special report published last October by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the United Nations body charged with assessing the science of the crisis. This heavyweight international group put a hard deadline on action to avoid a full-on sabotage of our environment: 12 years. If carbon emissions continue to mount, by 2030, it will be too late.

Between Thunberg and the dozen-year deadline, Generation Z (those born in the mid-1990s and after) got organized. In Canada, young Quebecers applied to launch a class action suit, accusing the federal government of infringing on their rights by failing to have an effective plan to cut carbon dioxide emissions. The proposed suit, initiated in late November by ENvironnement JEUnesse, joined similar legal cases in the Netherlands, the United States, Belgium, Norway, Switzerland, Ireland, New Zealand and Colombia.

Students and youth staged sit-ins at the offices of members of Parliament in many of Canada’s major cities. Kids still too young to vote began skipping school to picket the inaction of their governments. New protest organizations — Climate Strike Canada, Fridays for Future — started springing up in city after city. This is the social media generation, so organizers linked up through the Slack app and rallied people by Facebook. Orchestrated strings of actions were happening across the planet. The youth were rising. So much was happening, it was like tracking a speeding bullet to keep up.

And this day, March 15, 2019, was to be the grandest event of them all.

I arrive early and take refuge from the cold at the University of Toronto medical school across the way, rubbing my hands together for warmth and humming a Joni Mitchell song: “By the time we got to Woodstock, we were half a million strong.… We are stardust, billion-year-old carbon. We are golden, caught in the devil’s bargain, and we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden.” Is this the turning point? Is this the generation that will save us?

The shouting starts at noon, half an hour before the event. It is muted, like practice chants: “We want our future! The trees are not pleased!” I follow a trickle of puffy-vested protesters assembling in front of Queen’s Park, the Ontario legislature. Some are mothers with small children. Some, camera-ready politicians or longtime campaigners. Others, the Generation Zs who organized the thing. In all, perhaps a few hundred, far fewer than I expected. I am crushed.

Six weeks later, early on Easter Monday, I am having coffee with Aliénor Rougeot at the University of Toronto. She is taking a short break from studying for her final exams to meet with me. At 20, she is one of the leaders of Canada’s climate strike movement and is the main organizer of the protests in Toronto. Raised in France, she fell in love with Toronto and enrolled at U of T, her mother’s alma mater, a couple of years ago to study public policy and economics. Her parents and younger brother moved to Canada along with her.

She’s tall, elegant, crackling with enthusiasm. She started caring about the environment when she was 10. Her mother composted at their home in the south of France and patrolled food waste. This, and growing up in the countryside, set what Rougeot calls her “baseline” attachment to nature.

By high school, Rougeot had become passionately immersed in human rights and women’s rights. Then, one day, she had a flash of insight: “Wait! Nature and environment and human rights tie together with the issue of climate change!” Now she calls herself an activist for climate justice, and that label encompasses everything she cares about: climate refugees, wars, water scarcity, heat waves, storms, floods. And epidemics. What if she wakes up in five years and a whole neighbourhood has fallen to a weird illness? “It’s just terrifying,” she says.

She’s unperturbed when she talks about Toronto’s turnout for the March protest. It was big in Montreal, where about 100,000 joined in. Plus, as I had read in the news, 1.6 million students showed up at rallies in more than 120 countries. Despite Toronto’s pallid showing, it seems this movement has legs.

Rougeot is training her focus instead on Friday, May 3, the next day of global protest. She is invigorated by the non-violent Extinction Rebellion demonstrations started in the United Kingdom that are in full flight. Protesters in London shut down parts of the city, blocking bridges and occupying public spaces for days on end.

“I think it’s absolutely brilliant,” she says. “I wish we could say, ‘We’ll play by the rules.’ But some of our governments don’t seem to be playing the gentleman’s game.…We’re kind of fed up. We can’t have a conversation anymore.”

But as passionately as she believes in the need to grapple with the carbon load in the atmosphere, she also believes in civility. A lack of respect on the part of governments, citizens and corporations is what got us into this dilemma, she reckons. Respect for each other, for other species and for the planet is what will get us out. It’s going to take compassion and love to fight this ecological crisis, she says. Her words feel like a stark counterpoint to the belittling political discourse in parts of Canada and other countries at the moment.

Rougeot’s objective is strikingly commonsensical. It’s not anarchy or bloody revolution or a new world order. Instead, she and her generation want to persuade government leaders to meet with them. And then, to not just listen to their demands, but also take those demands deadly seriously. In other words, the aim is to use the power of youth to shift the responsibility for fixing the climate crisis back onto the policy-makers who have not just the ability, but the duty, to do it.

“People have got to realize that nothing else will matter if we’re dealing with nothing but climate disaster,” she says.

She stops talking all of a sudden and looks me straight in the eye. “I do hope people are not relying on the youth entirely. Our job is to be able to go safely back to school and know that our government has our back.”

Rougeot and I part ways just north of Queen’s Park, where those who govern Canada’s most populous, wealthiest province assemble. This seat of power sits in a leafy park by U of T’s ivy-clad campus, just south of the Bloor Street shopping stretch known as the “mink mile” for the price tags of its ritzy designer goods. Here is the nexus of crown, gown and town, the very institutions needed in this urgent conversation about our civilization. The lawmakers. The scientists. The profiteers.

The actions of these adults are under the laser focus of the appalled generation that has now realized it cannot trust them to work together for the good of all citizens. These are the same kids who, even if we stop emitting carbon into the atmosphere today, will have to deal with ugly fallout from what’s already there.

I wander over to Philosopher’s Walk, the tree-lined sanctuary running between my old school, Trinity College, and the Royal Ontario Museum. When I was Rougeot’s age, like her, I was living on this campus. A recent transplant from Regina, I too immersed myself in what I considered the prime injustice of the day. Then, it was the lack of rights for women. Marches. Protests. Banners. Raised voices. Righteous outrage. Certainty. Later in life, that morphed into anguish over the environment and more rounds of protest.

Late one rainy October evening in 1981, when I was 20, I marched from Queen’s Park up this same Philosopher’s Walk with a cabal of other feminists, vowing to take back the night. We were aghast that women didn’t feel safe walking alone after dark. It was the symbol of our inequality, and we were in full revolt. Suddenly, walking along the same path now, I recall that a photograph of me and a few other chanting protesters appeared on the cover of the student newspaper the Varsity. I summon up that long-ago black-and-white image, shaking my head. We were so confident that we could make a difference. We were so young.

All of a sudden, grief overwhelms me. These tragedies that Rougeot and Thunberg and the others are railing against were born on the baby boomers’ watch. Wasn’t this our fight? Weren’t we the generation that launched the environmental movement and saved the whales, conquered acid rain and healed the ozone hole? Weren’t we the ones who connected the dots for the first time on how humans are destabilizing the life-support systems nature wrought painstakingly over billions of years? It was our job to make sure these kids didn’t have to live through the fires, the floods, the mudslides, the heat waves. Instead, they’ve spent their entire lives enduring them. And now, in the ultimate betrayal, we’re pinning our hopes on them to forestall something even worse.

Adult after adult has confessed that we’ve dropped the ball — and implied that we adults have forsaken our chance to make things right on our own. UN Secretary-General António Guterres said recently that we need the leadership of youth to rescue the planet. “These schoolchildren have grasped something that seems to elude many of their elders: we are in a race for our lives, and we are losing,” he wrote in the Guardian.

I hang my head. Did my generation lack commitment on climate — or only courage?

Kids are also feeling the weight of our failure. Neurologically speaking, the adolescent brain is wired for idealism. Teens want to change the world. But what if, at the same time, they’re hearing that the world is coming to an end?

Mental health professionals in several countries have started to offer counselling services to those of all ages suffering from climate grief. “I think that complicated emotional response from adults and youth is something we’re all grappling with,” says Katie Hayes, a PhD candidate in public health at the University of Toronto and a member of the Canadian Climate Psychiatry Alliance. “I think there’s a lot of grief and guilt and uncertainty about how we move forward.”

And a sense of impending doom. Hayes cites an Australian study that uncovered pupils who thought the world would end before they reached adulthood.

Rougeot says that whenever children show up to do prep for the demonstrations, she takes their emotional pulse. “Imagine a 10-year-old hearing every day that in 12 years your planet is dying. Before we make posters, I say: ‘Are you okay?’”

Hayes says these kids are done with clinging to hope. Instead, they want what she calls “active hope.” That means confronting grief, anger and fear and translating it into action. In other words, they’re wired for idealism after all.

Which leads me to my big question: How far are these kids willing to go?

Hayes laughs. “That’s anyone’s guess.”

The day of another climate strike has arrived — Friday, May 3. Rougeot has invited me to the preparatory meeting at a Quaker meeting house near the U of T campus. Here, perhaps a dozen students plus some adults and smaller children will gather to make signs and practise songs for a couple of hours before the protest.

Rougeot has been on a CBC radio show this morning telling Canadians about the youth movement and is on her phone checking feedback. She wants today to be the day Canada’s biggest city comes alive with climate outrage. Already, she’s received word that schools are bringing hundreds of pupils. Some teachers have told her they’re encouraging their students to skip school and join the strike.

Right now, she’s leading some of the students and grown-ups through practice chants. Her favourite? “Rod Phillips, where are you?” Phillips is Ontario’s minister of environment, conservation and parks (a position he will soon lose when Premier Doug Ford shuffles his cabinet), and Rougeot has been in touch with his office to ask for a meeting. No go.

“I said I was available for the next month, and they said he’s away for the next month,” she says, arching her eyebrows.

Olivia Packer, 13, is helping to organize things, clipboard in hand. Her mother drove her here this morning from Mississauga, Ont., and both are going to the march. When I ask her what she wants, the Grade 7 student echoes Thunberg: “Let politicians act as if their house is on fire.”

She’s got a detailed, lucid list of other asks, ranging from laws to taxes to cutting down on meat consumption to using more renewable energy to the key demand that governments declare a climate emergency. It strikes me that this generation is merely asking adults for what a psychologist would call validation. Yes, what you’re seeing really is scary. And yes, we’ll do something about it. Even on that modest request, few governments are coming up to the tape.

“Are you mad?” I ask her.

“I’m very mad,” Packer says with great force. “Things shouldn’t be this bad already.”

In one corner of the dining room, preschoolers are sprawled tummy-down on the floor, legs in the air, making posters with intense concentration while their mothers watch. Along another side of the room, a woman is organizing a display that will give protesters the chance to write on a ribbon what they fear to lose from the climate crisis. These ribbons will be tied on a horizontal standard that will have pride of place at the march. Along the way, adults will be encouraged to take one as a vow to protect what’s written on it.

It feels a little like a craft club — ribbons, poster board, markers — except that so many of the adults are so vociferous. One woman with a small child in tow is loudly denouncing the Ontario government’s lack of meaningful action on the carbon crisis. A man is jabbing his finger in the air to punctuate a point about how dangerous these times are, propounding to the teens. The students are listening respectfully, gracious to a fault. I ask myself if there’s such a word as “adultsplaining.”

Alik Volkov, then 17, has ducked out of his Grade 11 classes in Richmond Hill, Ont., to be here. He put a flyer about today’s strike on every locker at his school, encouraging others to skip class. To his amazement, his teachers didn’t make him take them down, he tells me, eyes widening. But it didn’t matter. He’s the only one from his high school here today.

“I’m not much of an activist at all, but I just want to help,” he tells me. He’s sitting at the table, carefully lettering a sign that says SAVE OUR HOME. Like so many others involved in this movement, Thunberg is his hero. “When I heard what she’s doing, I said, ‘Finally.’ And I blamed myself for not doing anything before,” he says.

The marshals assemble us, and we head off for the march, wending our way through the streets of downtown Toronto — by the shops of Bloor Street, down Philosopher’s Walk, finally to Queen’s Park where we will stop for speeches, gather the masses and then march to city hall. It’s overcast but so much warmer than during the rally in March. We round the corner to the legislature’s front doors, chanting, waving signs (Listen to Greta!), waiting to catch our first glimpse of the crowd. Will there be a huge throng, as we expected?

Again, disappointment.

“I don’t know what happened to the numbers here today, but this is not the end!” Rougeot declares to several hundred people after taking the microphone.

I stay for the better part of another hour listening to speeches about this devil’s bargain we are caught in, longing for evidence that the rising will take hold. I notice students with Thunberg-style pigtails and banners boasting images of Thunberg’s face. One sign is particularly sobering because it is so true: We are the last generation that can save our planet!

Finally, I leave in despair. Go home, strip off the Dylan T-shirt that I have once again worn as a talisman of change. I throw the shirt into the laundry basket, wondering how I could ever have worn it without irony. Do revolutions ever succeed?

Maybe they do. Later, I learn that after I left the rally at Queen’s Park, more people arrived. By the time they got to city hall, they were, well, not Joni’s half-million strong, but maybe 2,000. Enough that Rougeot will declare, ebulliently, that Toronto has at last awoken. A turning point, she says, but certainly not the peak.

It was our job to make sure these kids didn’t have to live through the fires, the floods, the mudslides, the heat waves. Instead, they’ve spent their entire lives enduring them.

Ten days later, Rougeot is back at Queen’s Park. NDP members of the provincial parliament have brought forth a motion to declare a climate emergency. Rougeot and other climate strikers are there to support it. Given that Conservatives have a commanding majority of the seats, they don’t expect the motion to pass.

That’s despite the alarming news dominating the headlines the week before. A landmark UN report found that a million species are at risk of extinction, a decline unprecedented in human history. That rate of decline is speeding up. The web of life that supports us all is fraying.

And the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere has breached 415 parts per million (ppm) for the first time since humans have been on the planet. It’s part of the inexorable, accelerating rise from the norm of 280 ppm that we had before we started burning fossil fuels. It represents yet another psychological boundary crossed, another threat to life as we know it.

In the Ontario legislature, the motion to declare a climate emergency fails. Rougeot tells me that Phillips, the environment minister, wasn’t even there for much of the debate, only returning to vote against the idea. She is heartbroken.

“I felt like I got slapped in the face with so much disrespect,” she tells me in an email.

But the kids are not giving up. Thunberg and thousands of other youth activists are accelerating the pressure. Not only will there be protests around the world throughout the summer, but they’ve also summoned adults to join a worldwide general strike — Canada’s will be on Friday, Sept. 27, at the end of a week of global climate action.

Celebrities have added their weight to the call, including writers Margaret Atwood, Barbara Kingsolver, Naomi Klein, Bill McKibben and Rebecca Solnit, actors Maggie Gyllenhaal and Mark Ruffalo and scientists Tim Flannery and Michael Mann.

“We hope all kinds of environmental, public health, social justice and development groups will join in,” they wrote in the Guardian in May, “but our greatest hope is simply to show that those working on this crisis have the backing of millions of human beings who harbour a growing dread about our environmental plight but who have so far stayed mostly on the sidelines.”

Will it be enough? The IPCC’s dozen-year deadline is down to 11 years. And that’s not for starting the transition to net zero carbon emissions; that’s for being well on the way there.

Signs are pointing both ways.

In June, Canada’s House of Commons declared a climate emergency. The following day, the Liberal cabinet approved the construction of the controversial Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, which, if built, will take more bitumen from the oil sands to market. The conflicting moves mirror elections in May in the European Union and Australia. Europe went greener. Australia voted in a fossil fuel-friendly government. Push, pull. Forwards, backwards.

Here’s what I see from my perch of generational guilt. This is a hinge moment in human history. It is the last chance to avoid the catastrophes that carbon has in store for us. Quite simply, we will either listen to the kids and take action. Or we will doom them, betraying them yet again.

For more of Broadview’s award-winning content, subscribe to the magazine today.

What, really is climate change, and why blame it on our carbon emissions?

The earth was warmer during the age of the dinosaurs, then came the big ice age and the whole northern hemisphere was covered with meters of ice. Since then, the earth has been gradually warming up to a point that is alarming, and there is really nothing that we can do to stop it except to pray that the good Lord will only come at us with a mini ice age this time!! The sun is just too hot and so the ice melts regardless of demonstrations and/or carbon taxes nor scare tactics.

It is good to clean up our countryside and oceans, get rid of the plastics and other chemicals. Train people to clean up and the best way to do this is to not litter in the first place

Alana Mitchell is quite right. Young adults and their children now face a future so wretched that the 1930s and early 1940s are looking good. After 1945, we assumed, as have all generations until now, that the condition of the basic conditions of life could be taken for granted. Then, we could afford to focus narrowly on creating personal and community character and making a living.

In 2019, the stability of the condition of the conditions of life is in question. This presents an unprecedented existential and civilizational threat, one which we have yet to identify clearly, much less understand.

A place to begin is to understand that in the mid-20th Century, we knew virtually nothing of the cumulative power of human persons, acting together in taken-for-granted cultures, to shape both the human futures and that of our Earth.

Even today, we have yet to come to terms with the core lesson of Genesis chapter 1: the feature that defines us is that we share with our Creator the capacity to embody our imagination in physical reality — our word also becomes flesh. The difference is that God’s word is always life-giving. For good and ill, ours is substantially more varied and variable.

This means that the environmental/climate crisis is not simply a physical affair — one which we can “fix” or “solve” with STEM. (Sadly, this view dominates our Modern cultures.) Rather, climate disruption is best understood as but one of many symptoms that, when taken together, suggest that Modernity has peaked; that our Modern/Industrial cultures are now in a long-term decline. If at all true, then we who are Modern have no long-term future as Modern/Industrial people living in Modern cultures.

The implication of this line of thought is clear: we only make things worse by trying to hold on to Modernity, to improve and even redeem it. As adults in the room, we will develop the wit and courage to see ours as a truly rare time in which our new work is to let go of Modernity, out-grow it and turn our attention to the co-creation of the next form of human civilization.

This is a challenge that we and young adults need to see and embrace together.

Your views of history are distorted by Western civilization and culture. For most Asian and African nations, starvation and poverty have been a way of life since we “civilized” nations exploited the “third world”. I’m sure most in these countries don’t take life for granted.

The 50’s and the mid 60’s the “civilized” nations were waiting for the results of the cold war. They knew man was capable of annihilating themselves.

1970’s the western world was looking for fuel alternatives. If we did a good job back then, perhaps we wouldn’t have “man made” global warming, or be blaming it on something else.

Y2K ring a bell? Again the world was certainly going to end, those computers were going to fail us all.

Today’s social media and technology (in my opinion) feeds mass hysteria and (dare I quote D. Trump) fake news. By this I mean anyone can come up with a scientific result or prediction, slanted to state a case. As far as environmental issues, we can only accurately measure back 150 years. Beyond that no one cared if it was hot or cold where they lived, they worked around it.

My view is God made a world that was “very good”. Yes fallen man has distorted it, but it’s God’s creation, not ours. If He chooses to destroy it, we have nothing to say. However we must live within its variables, which we have done successfully for 1000’s of years.

Here I am, 74 years old, and I have failed my grandchildren. Now I hope they will save themselves, but they cannot do it alone. If all you as an adult can do is change the way you live, recycle, reuse, refuse the plastic cup at McDonalds, then so be it, but also be an advocate. And vote for the climate in October.

Thank you for the article. Whenever somebody tells me to panic (about anything) I instinctively take a deep breath and refuse to do so. Panic does not inspire clear thinking. And it’s clear thinking that is necessary. There is indeed climate change and we must take it seriously. There are adults in the room who are not panicking and taking it seriously. I point those who take climate change seriously and refuse to panic based on the use of world-ending apocalyptic language to watch Peter Robertson’s February 11, 2019, Hoover Institution interview with Bjorn Lomborg. The interview is called the “Cost-Effective Approaches to Save the Environment”. (see youtu.be/5QyXduteiWE) Bjorn Lomborg is president of the Copenhagen Consensus Center and speaks on climate change. It takes climate change seriously and rejects any language of panic. If you are looking for resources to talk about your children’s anxiety over climate change this will put it in balanced perspective.