My heart thuds in my chest as I hurry around the periphery of the town. I have a feeling I’m late to meet someone, and I’m nervous because it’s someone I want to impress.

That someone is multiple someones, really, and they’ve been dead for 322 years. I’m in Paisley, a town just outside of Glasgow, Scotland. It’s known for the ubiquitous paisley pattern you see on scarves and bohemian skirts everywhere. It’s also known for its witch hunts, and it’s the site of the last mass execution of witches in Western Europe. The remains of seven so-called witches are buried here: Agnes Naismith, Catherine Campbell, Margaret Fulton, Margaret Lang, John Lindsay, James Lindsay, and John Reid.

That’s why I’m here. I spent some time in Scotland over the summer, and it was a special trip for me because it’s where my family came from before settling in Canada.

As someone who has always been billed as a little odd by their peers, and who uses herbs for healing and cleansing, I view these dead witches as kin. So I carry a few spindly flowers I picked outside, and a friendship bracelet that’s just worn itself off my arm. My plan is to sit with them at their tomb on the outskirts of town for a few minutes at least, lay my offerings there, and keep them company for a while. I left my long-suffering partner in a coffee shop for this trek, knowing it’s the sort of thing you’re supposed to do alone.

More on Broadview: After coming out, astrology became my remedy for dogmatic religion

Paisley is a town that is a little down and out. As I walk the kilometre or so to the grave site, I pass gorgeous Victorian buildings, their windows smashed out like broken teeth.

When I arrive at the place that my phone is guiding me to, I stop short in confusion. I see one business: a funeral director’s office. Several lanes of traffic converge at the spot. I count them: 13. I can’t see a tomb or a memorial of any kind. I think I must be in the wrong place, but I can’t leave without exploring. I peer across the road, into the middle of the busy intersection, and spot it: a manhole.

The ashes of seven bodies are buried under it. I can’t get there from where I’m standing: I have to cross the street, over several lanes, then do the same thing on the other side. Finally, I’m only two lanes away from it. But the lights aren’t set up such that the traffic ever stops driving over it. I have to skip out onto a median, and run out into the road when no one is coming. I run out, and there’s enough time only to quickly peer at the memorial plaque and horseshoe covering the grave, and snap a photo. “Pain endured, suffering inflicted, injustice done,” it reads. There is not even time to lay my offerings on the grave; a royal blue Toyota Avensis narrowly misses my toes as I scuttle back to safety on the median.

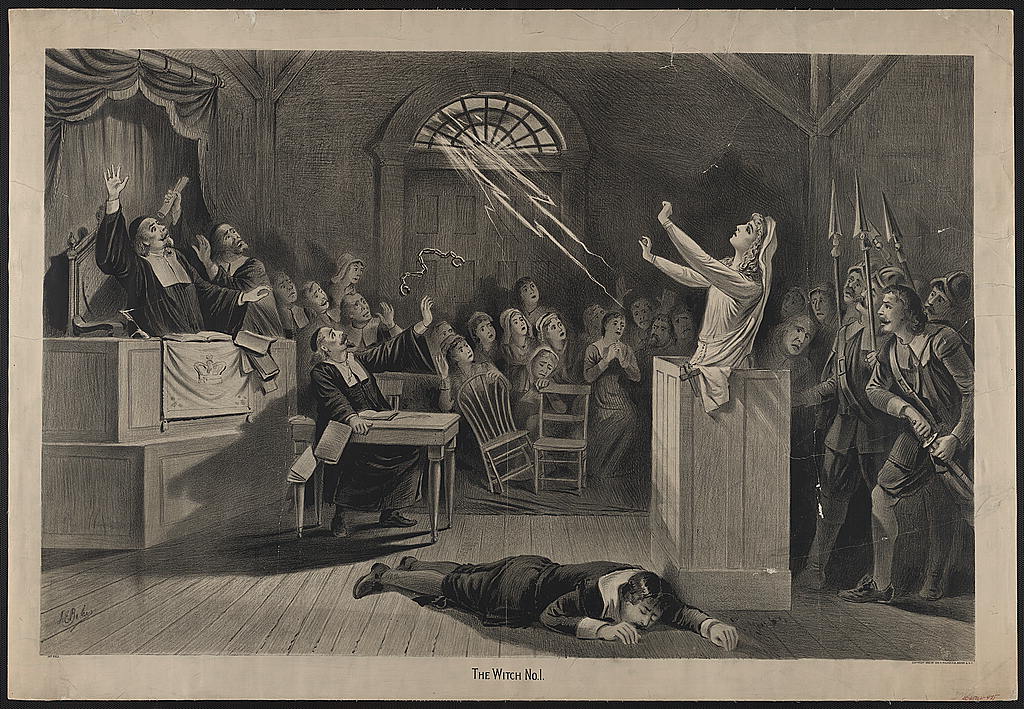

The Paisley witches, sometimes also referred to as the Bargarran or Renfrewshire witches, have rested here at Maxwellton Cross and George streets since 1697. During the first five months of 1697 in Renfrewshire, more than 30 people were suspected and accused of practicing witchcraft, a crime at the time. Hanging people deemed to be witches was a normal and natural thing to do in the 17th century. Seven of those accused were, according to lore, hunted down and held in a tolbooth building. They were tortured with sleep deprivation, and eventually confessed to acts of witchcraft and making pacts with the devil. They were marched to Gallows Green, garrotted (or strangled), and burned. Their deaths marked one of the last mass executions for witchcraft in Western Europe.

Before they died, though, two of the witches, Agnes Naismith and Catherine Campbell, put up a fight. They kicked and screamed the whole way to their deaths, and it’s said the women put a curse on the town, condemning their accusers and all of their descendants.

An iron horseshoe was screwed into the manhole to protect the town from the witches’ curse. If the horseshoe was ever removed, it was said, tragedy would befall Paisley. Since 1697, the horseshoe has become dislodged several times, and each time, accidents and even deaths would occur and be attributed to the dead. Just about every tragedy, for years afterward, was blamed on the witches.

That prejudice has yet to be put under review. It didn’t just happen in Scotland, it happened all over Europe and in North America, too. People, mostly women, deemed to be witches have been murdered all over the world for practicing their craft, being a little odd, or getting in the wrong person’s way. Some estimates put the number of people executed during the European witch trials alone as high as 100,000, with up to 26,000 dying in Germany. In Scotland, about 4,000 people were tried for witchcraft, and it’s estimated that up to two thirds of those were executed.

People continue to be hunted for practicing supposed witchcraft, with United Nations researchers estimating that thousands of people are killed for this each year.

I stop by the café on my way home from the grave to pick up my partner, and I ask the woman working what her thoughts are on the burial site. She doesn’t seem to want to talk about it, but the locals, she says, try to avoid driving over it, lest the horseshoe be dislodged again, heaping misfortune upon the town.

To me, it seems the state of the witches’ burial site is less about magic and more about ongoing misogyny and fear of feminine power, or what’s seen as feminine power. Liz Gardiner is chair of the local awareness group and charity Renfrewshire Witch Hunt 1697. Her role with the group, she explains, is “to educate local people and tourists about the reality of 17th century witch hunting, which was less to do with anything supernatural and much more to do with human prejudice, revenge, persecution and greed.” That prejudice manifested in cruel ways: witches throughout Europe were tortured with pinpricks and interrogations, hanged, and burned, as the Paisley witches were, and they were also sometimes drowned.

Her group is pushing to have a more appropriate resting place for the dead. “We would love to have the memorial more respected and attended,” she says. “It’s impossible to move the grave as that is where they are buried, but we could create something around it to protect it. The idea of the drop-in centre is to provide a space where people can come to learn about the story and the issues. Ideally, we would like to obtain an official pardon for those who were murdered.”

Gardiner says council is aware of their wishes to have the witches’ resting site better memorialized, but John McIntyre, one of four councillors responsible for Ward 4, is noncommittal when asked what, if anything, Renfrewshire is doing in this regard. As for why the site isn’t better outfitted, he says:

“I think there was a feeling in the past that trials for witchcraft had often been miscarriages of justice and an abuse of the system. I believe a lot of people thought it was something to be forgotten and not commemorated.”

What is sure, though, according to McIntyre, is that people are interested in the injustices done, and in witchcraft in general.

Gardiner is hoping these kernels of interest lead to something bigger and more meaningful.

“It behooves us to apologize and make amends.”

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

Thank you for the article. To sharpen the historical facts of those accused of witchcraft that the article highlights: 35 men and women were originally accused. 7 went to trial and two off them were men. The jury (probably all male) wanted to acquit them. The presiding judge lectured them and told them that they had to find these men and women guilty of witchcraft or they (the jury) would be responsible for all the evils that would happen. The original accusation was made by an eleven year old female who told her mother that the servant had cursed her. These are females accusing men and women of witchcraft. The writer concludes this trial is misogyny (by definition the hatred of women mostly by men). She might be right in the context of the day provided one accounts for the political and social context of the trial. Though whenever one drills down to the facts there are often more selfish motives uncovered in the hearts of men and women which complicate branding it by any single term.

So three of the seven were men – but the headline concludes “misogyny.” And from the other comment here, we read the accuser was a female? Why not misandry and misogyny?