Just a decade before Canadian Confederation, an Anishinaabe woman named Nahnebahnwequay faced eviction from her home and denial of her Indian status.

Nahnee, as she was known to friends, or Catherine Sutton, as she was known in English-speaking circles, was born a member of the Mississaugas of the Credit and had grown up on the shores of Lake Ontario under the care of Anishinaabe chief Kahkewaquanaby (Peter Jones) and his wife, Eliza.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Fluent in Anishinaabemowin, Nahnee had received an education in English and was committed to mission work through the Methodist Church.

When her community at the Credit River was denied deed to their lands, Nahnee and her settler husband, William Sutton, accepted the invitation of the Nawash Anishinaabeg to join them near present-day Owen Sound, Ont. in 1846. The name of the community, Nawash, is from the Anishinaabemowin word “neyashingaming” which means “point of land.” There, they worked hard over several years to clear land and establish a homestead.

But 11 years later, in 1857, Nahnee found herself deprived of both her land and her annuities as a member of the Nawash First Nation. A group from the Nawash, without the blessing of their community, had travelled to Toronto and ceded their land through a treaty — land that included Nahnee’s farm. The injustice turned her into an activist.

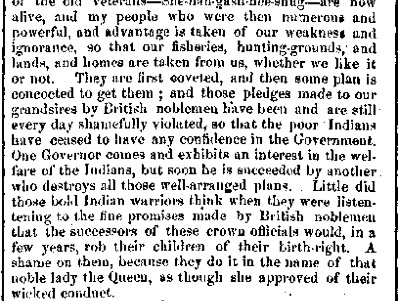

Eventually taking to the pages of The Christian Guardian on May 28, 1862, she expressed her rage against the government of the Province of Canada: “[T]hose pledges made to our grand sires by British noblemen, have been and are still every day shamefully violated, so that the poor Indians have ceased to have any confidence in the government.” Nahnee’s would be the last Indigenous voice published in The Christian Guardian and its progeny for many years to come.

***

As Broadview continues its exploration of this publication’s historic relationship with Indigenous communities, the period surrounding Confederation reveals many is compelling insights.

Earlier that century, The Christian Guardian regularly published news of missions to Indigenous Peoples in British North America. Kahkewaquanaby and other young Indigenous men had frequent bylines in the Methodist paper.

In the mid-1800s, however, the next generation of Indigenous Christians no longer wanted to become missionaries to their own people, and knowledge of Indigenous communities and their challenges among settler Methodists began to wane. Just as Canada was coming into being, The Christian Guardian lost its Indigenous voice and betrayed Indigenous aspirations. The reasons for this include shifting demographics, emerging national ambitions, changing religious priorities and insecurities, and evolving racial prejudices.

Nahnee was not completely alone on the pages of the Guardian. Other contributors, like Anishinaabe missionary Alan Salt, did their best to keep settler injustices on the Methodist church’s radar. Salt was from Alderville First Nation (remembered by the Anishinaabeg as Pemedashkotayang, meaning lake of the burning plains). Salt worked all through Upper Canada and as far west as Garden River, a name which is the literal translation of Ketegaunseebee in Anishnabemowin, near Sault Ste. Marie. His own accounts of his mission work were published in The Christian Guardian in the 1860s. But instead of highlighting Indigenous perspectives, the paper focussed instead on consolidating Canadian sovereignty from coast to coast to coast — an agenda that left little to no room for Indigenous points of view.

***

In 1857, the same year that Nahnee lost her farm, the government of the Province of Canada passed the Act to Encourage the Gradual Civilization of the Indian Tribes. This act, introduced to the provincial parliament by none other than John A. MacDonald, helped lay the foundation for what became, in 1876, the Indian Act of the Dominion of Canada. Among other things, the Gradual Civilization act declared that Indigenous women who married non-Indigenous men would forfeit their status and rights as Indigenous people. Nahnee was among the first to suffer its terrible consequences.

More on Broadview:

“This is not an uncommon story for the time, and stories like it continue into the present,” says Benjamin Hoy, professor of Canadian and American history at the University of Saskatchewan. “Governments like clear categories. It makes it easier for them to govern.” The categories of “Indian” and “non-Indian” like the categories of “Canadian” and “American” historically bear no relevance to the actual relationships that sustain Indigenous communities, he explains.

The colonial pattern of divide-and-conquer that robbed Nahnee of her farm is echoed in the present-day conflict in British Columbia over the construction of the Coastal GasLink Pipeline. The project, which runs through unceded Wetʼsuwetʼen territory, was approved by an elected band council of the Wetʼsuwetʼen, a model of governance foisted on Indigenous communities by the Indian Act. The Wetʼsuwetʼen hereditary chiefs, whose authority the Canadian government doesn’t recognize but who embody the community’s moral centre, have not given their full consent.

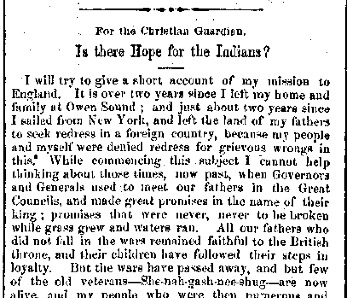

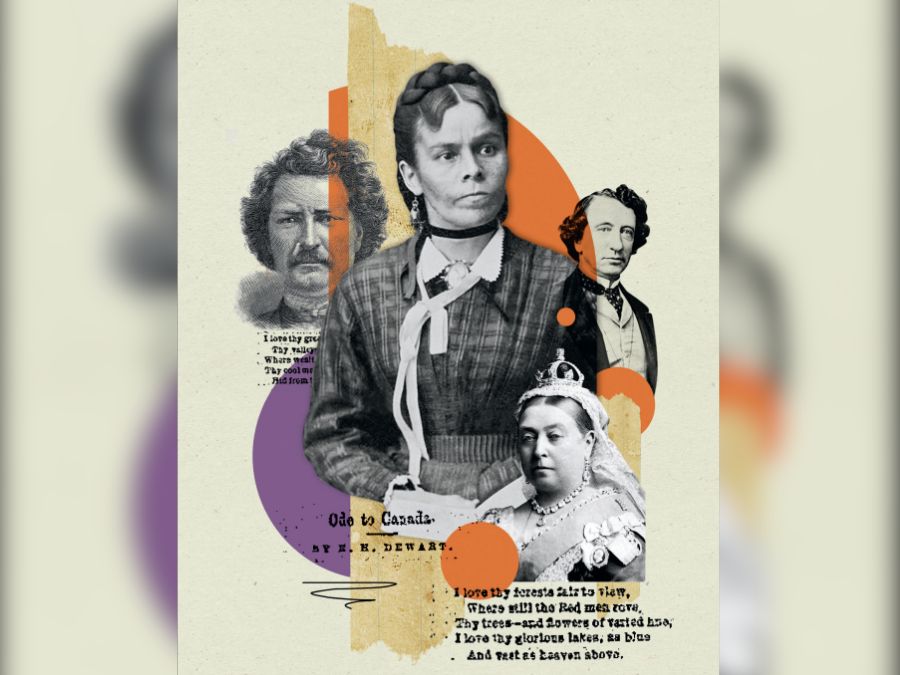

Nahnee worked hard to reverse the new legislation and reclaim her land for her people the Nawash. She even managed to obtain an audience with Queen Victoria in London, England, on June 19, 1860. Two years after her return, The Christian Guardian published her account of her travels to seek redress “for grievous wrongs,” broken promises “that were never, never to be broken while grass grew and waters ran.”

In the remaining years leading up to Confederation, Indigenous population and influence declined across British North America, playing into the colonial assumption that “superior” European ways would supplant Indigenous culture. “This was a moment in history,” says Hoy, “in which Canadian politicians believed Indigenous people were going to disappear and no one knew if Canada would survive as an independent country.” Shamefully, The Christian Guardian fell right in step, silencing Indigenous voices and bolstering the colony’s nation-building efforts.

On July 3, 1867, in the first edition following the Confederation of the Dominion of Canada, The Christian Guardian published “Ode to Canada,” a poetic celebration of the new nation by H.K. Dewart. Nineteen stanzas long, the poem paints the picture of a paradise that God created in North America as if for European settlers alone. It contains but a single line mentioning “the Red Men,” the slightest nod to Indigenous peoples.

I love thy forests fair to view,

Stanza nine in “Ode to Canada” by H.K. Dewart

Where still the Red men rove.

Thy trees – and flowers of varied hue,

I love thy glorious lakes, as blue

And vast as heaven above.

“This is an interesting poem,” says Colin Osmond, professor of Indigenous history at the University of British Columbia. “It has so much to do with the myth-making that came along with Confederation.” He notes how the phrase “Where still the Red men rove” acknowledges the presence of Indigenous people without challenging the myth that God wants North America colonized. “Indigenous people had to be seen not as owners of these spaces,” says Osmond, “but as parts of these spaces.”

***

Confederation marked an abysmal turning point in The Christian Guardian’s coverage of Indigenous issues. In the years following, The Christian Guardian outsourced its coverage of Canada’s western expansion to the Toronto Globe, edited by George Brown.

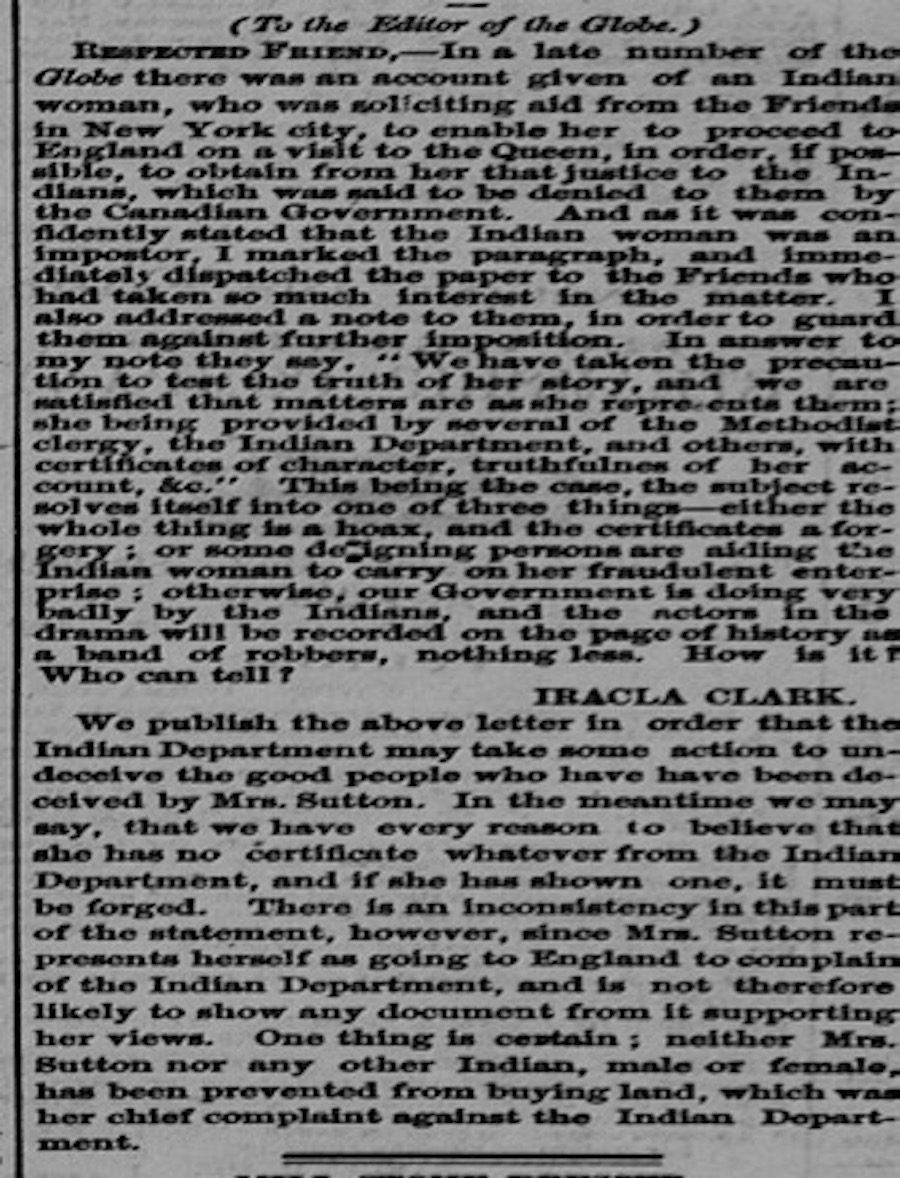

Though a heralded as a champion for abolition in the United States and Black settlement in Canada, the Globe’s views were much less sympathetic toward Indigenous rights. The paper took even more interest in Nahnee’s story than The Christian Guardian but for different reasons. It hounded her on her trip to England. On May 23, 1860, an article entitled “The Indian Imposter” stated falsely that Indigenous people could own land under the new Gradual Civilization Act and claimed that Nahnee was someone of bad character who was “deceiving” international audiences when she spoke on the issue.

The Christian Guardian editors knew Indigenous missionaries such as Alan Salt, or others working in what was then Rupert’s Land, who might have given insight into the Indigenous point of view. The Methodist paper turned to the Globe republishing its coverage of the Métis uprising in Red River in 1869.

Deeply concerned by the plans of the new Canadian government to survey and possibly confiscate their lands, the Métis had called up Louis Riel to lead them in their protest. Riel’s demands included a representational government that included both French and English as well as Indigenous voices. The Globe’s report, carried in The Christian Guardian, dehumanized Riel and his followers alluding pejoratively to their French, Catholic and Indigenous identities. It even suggested, falsely, that the Métis were preparing a massacre of Canadian settlers. The Christian Guardian offered no editorial comment to counter these views. This could be one of the lowest moments in The Christian Guardian’s coverage of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

***

The pages of The Christian Guardian around the time of Confederation reflect a changing relationship between the press, the church, Indigenous people and the idea of Canada. As the numbers of Indigenous people diminished, interest in church unity and influence within Confederation eclipsed Indigenous voices and concerns. Stories of the theft of Indigenous land and erasure of Indigenous identity, like that of Nahnee, were eventually replaced with stories that sowed fear and prejudice against Indigenous people such as the Métis who dared to challenge the new Dominion’s authority.

As for Nahnee, she and her husband were eventually granted permission to purchase the farm they had built. But she was unable to get the Gradual Civilization Act rescinded and never received her Indigenous status back. Neither did she succeed in having the land returned to the Nawash people. Her community remained bitterly divided between those who approved and disapproved of the way it was given up. Much of the huge tract of land, that Queen Victoria herself had declared in 1847 to be Anishinaabeg property, was eventually sold off by the colonial government.

And in 1867, in what can only be described as numbing indifference to injustice, The Christian Guardian began to print advertisements directing settlers to speak to the Indian Agent if they wished to acquire the land that had once belonged to Nahnee’s people.

Rev. David Kim-Cragg is a historian, author and minister at St. Matthew’s United in Richmond Hill, Ont.

Vanessa Kennedy, who served as a sensitivity reader for this article, is an Indigenous consultant in Hillsdale, Ont.

THE PERIGOE FUND: This feature was funded through a generous gift from Revs. John and Lillian Perigoe to support Broadview’s coverage of Indigenous issues.

I am the 3x great granddaughter of Nahneebahweequy. I

I love 3 miles from her homestead where she was laid to rest. I go there often. Her daughter Sophia Ann Sutton Staves, my 2x great Grandmother is buried there too.

I am a member of the Chippewas of Nawash getting our family status back in 1999.

I was given her name Nahneebahwequay ( Standing Upright Woman)

By an Saugeen Ojibway Knowledge Keeper and Elder at a ceremony in 2012 at the Sutton Homestead which is now The Cobble Beach Golf Course in Georgian Bluffs in the County of Grey Ontario

You must be so proud of your great grandmother! It’s good to know that the Queen was supportive of Indigenous rights and valued the First Nations people. It’s too bad that she didn’t force the issue.