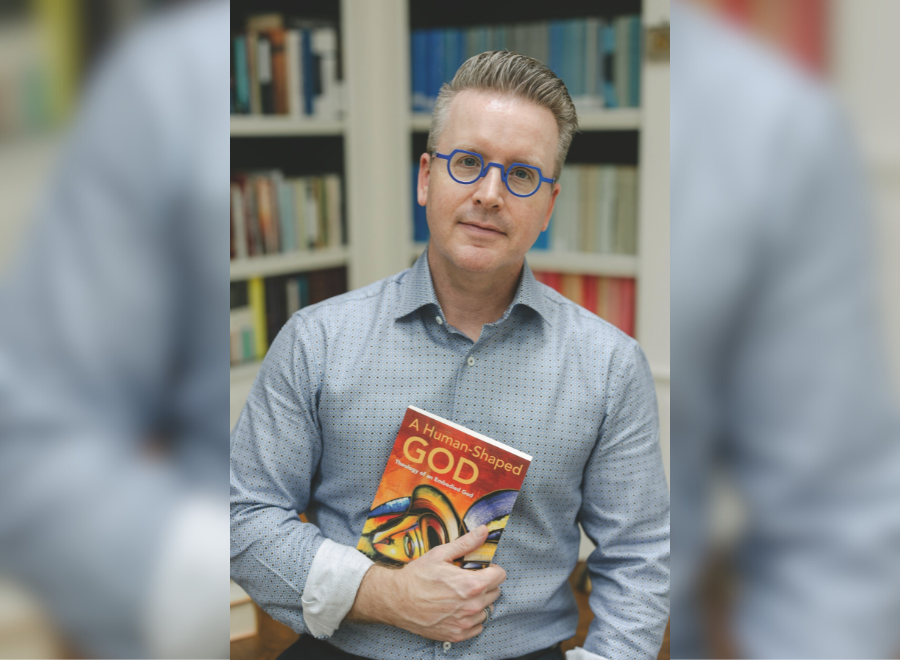

Rev. Charles Halton has thought long and hard about the human-like qualities of God. A biblical scholar and associate rector at Christ Church Cathedral in Lexington, Ky., Halton researches the bodily depictions of God in the Hebrew Bible — the Old Testament — and their continuity in how we understand Jesus as a divine figure in the New Testament. His latest book, A Human-Shaped God: Theology of an Embodied God, for which he won the prestigious Grawemeyer Award this year, explains how embracing God’s human qualities can inspire us to become better people.

Judith H. Newman, a professor of the Old Testament at Emmanuel College at the University of Toronto, spoke with Halton about his award-winning book, as well as omnipotence, metaphor and the role of emotions in theology.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

JN: Your book provocatively argues for a very different way of doing theology. Instead of thinking of God in abstract or transcendent terms, you suggest we imagine a biblical God with a body. How is God “human shaped” in the Hebrew Bible?

CH: I borrowed that from Benjamin D. Sommer, a biblical scholar and Jewish theologian. He describes embodiment as being located in a particular time, in a particular place, no matter your material formation. There are many different forms that God takes within the Hebrew Bible. The most prominent example is God’s location in the tabernacle, or later in the temple in Jerusalem. If you’re an ancient Israelite, you would travel to Jerusalem to offer your sacrifices in worship. That’s because you did it where God was located. So God was this person living in the Holy of Holies, the tabernacle’s inner sanctuary. But then you also have these more temporary manifestations of God, like when Moses meets the burning bush. God’s presence is there in a particular time and place. Once you start looking for embodiment in the Hebrew Bible, it appears everywhere.

JN: You take European theologians like the Protestant reformer John Calvin to task for trying to create a God without anthropomorphisms and contradictions. Why is it a problem to conceive of God as consistently transcendent, omniscient and omnipotent?

CH: I think there are a lot of problems with seeing God as omniscient, omnipotent — all these traditional ways in which western theology has conceived God. It makes us worse readers of the Bible. We see all of these human encounters reflected in the Bible between people and God — a God who manifests very human-like characteristics. But we have to read against the grain of the stories. Interpreters like John Calvin invented very sophisticated, interpretive rules to have the meanings of biblical passages mean the opposite of how they read on the surface.

The other problem, philosophically, with seeing God as omniscient and omnipotent is that in those conceptions, God cannot have a relationship with Creation and with humanity. Because classically, in theology, God is seen to not be affected by anything outside of God. God doesn’t have emotions because emotions imply change.

More on Broadview:

JN: Many people contrast the angry God of the Old Testament with the loving God of the New Testament. Are they right? What role should emotions play in theology?

CH: I think emotions should be a bedrock feature of theology. I don’t think it’s right to have this contrast between the wrathful angry God of the Old Testament and the loving God of the New Testament. You see tremendous accounts of God’s loving kindness, God’s fidelity, God’s patience, God’s care in the Old Testament. Those are far more numerous than accounts of God losing God’s cool and getting angry.

You also see Jesus getting angry in the New Testament — he throws over the tables in the temple and makes this whip and drives people out of it. There are other instances of Jesus seeming irritated at his disciples because they can’t stay up to pray in the time that Jesus crucially needs them to.

There is tremendous continuity between Old and New Testaments, where God is embodied in these various ways in the Old Testament, and then God has the ultimate embodiment in Christian imagination with Jesus. Fundamentally, Jesus is the same manifestation of how we see God’s embodiment in the Old Testament, including Jesus’ emotional life.

JN: Metaphor plays an important role in your vision of a new theological enterprise. Why are metaphors so important, and how do they work to shape human language and thought?

CH: Metaphors are crucially important because they’re really how we learn as human beings. Humans learn from seeing something concrete in the world and then abstracting from that. Religion in particular is heavily dependent upon metaphors, because we don’t have these direct connections with God. Even on an experiential level, if we feel the divine presence, we’re still feeling the divine presence through our sensory system of our body. So we need these metaphors to imagine who God is in order to connect with God and to build out a theology.

JN: In the chapter titled “God’s Body,” you write: “It is more productive to conclude that God embodies all genders simultaneously. We should, therefore, understand the God of the Old Testament as intersex.” What led you to think that God is intersex?

CH: If we take seriously the idea that humans are made in God’s image, and then we restrict that to only people who are biologically male or biologically female, we leave out a whole swath of humanity that just doesn’t meet up with that binary. So if we’re going to use that metaphor of being made in God’s image, we have to extend that image to all of humanity. Some of the earliest interpreters and close readers of the Bible saw these facets of the Creation narratives in Genesis. Some early Jewish commentators noticed that God created Adam first. But the actual wording of Hebrew says God created Adam, male and female. And so, some of the earliest Jewish interpreters said, “Well, that means that Adam was created as an androgynous being because God created Adam both male and female, encompassing the gender spectrum.”

When God went to create Eve, God didn’t create Eve out of Adam’s rib as people stereotypically think about it. The Hebrew word for “rib” actually means “side.” And so the way early interpreters imagined Eve’s creation was that God split Adam down the middle, because Adam had these male and female parts. Then God healed up those wounds, and then we had these two people.

Some other Christian interpreters built off this and said, “Sex difference didn’t occur until after the fall. And when we reach our heavenly state after we die, we will go back to a non-differentiated existence.” But the key point there is not that these folks were non-sexual; it was that they embodied the whole sexual spectrum.

JN: Despite your criticism of the western theological tradition, the early church theologian Augustine is important for you because of his emphasis on charity as the central principle of theology. You write: “The point of reading scripture is for us to become more loving and charitable people.” Perhaps Jews might argue that the point of reading scripture, and specifically the study of legal traditions, is to learn how to think critically and be just people. What would your answer be to that?

CH: I totally resonate with that Jewish approach. I did a PhD at a Jewish seminary. And I’ve been deeply informed by Jewish perspectives of the Bible. But I think that within Judaism itself, the study of Torah to understand how to navigate through the world in just ways is still built on love.

When we look at the Jewish tradition, what we see time and time again is that the rule that respects love is the one that wins out. As an example, let’s say it’s a Sabbath and we can’t work. That’s a stipulation in both the Hebrew Bible and Jewish tradition. But then we encounter a person who’s in desperate need, and they’re going to die unless they have help on the Sabbath.

The thing that God wants me to do is do the work and save that person. Not respect the rule to not work on the Sabbath. I think in the end, Jews and Christians come to the same place where loving God and loving your neighbour is this primal command and is the foundation of both religious traditions.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

***

Judith H. Newman is a professor of Old Testament/Hebrew Bible at Emmanuel College in Toronto.

We learn about God and his character as we read and discover the Psalms and the rest of the Bible.

Your unfailing love, O LORD is as vast as the heavens; your faithfulness reaches beyond the clouds. Your righteousness is like the mighty mountains. your justice like the ocean depths. You care for people and animals alike. O LORD.

Psalm 36: 5,6.

Interesting that the author would take a concept of a Jew and twist it to fit a narrative. First of all the Jews were commanded to go to Jerusalem for the feasts only, not because God was there.

If the Jews thought God was only present in Jerusalem, then why do the patriarchs pray to “God in Heaven”? Even Solomon who dedicated God’s temple prayed towards heaven. Read 1 Kings 8:22-53 Solomon even states that God will hear from Heaven.

As well we have Psalm 139 from David. What Jew would read that Psalm and think, “no I need to go to Jerusalem and meet God”?

Your theory is marked by your own words, it’s based on Greek philosophy and philosophy is based on man’s wisdom. Not always a bad thing, however it is a dangerous study, or else Paul would not have mentioned the warning in Colossians 2:8 But Theology is based on God’s wisdom, to which we are to seek, Proverbs.

Metaphors, are they not used because we as finite beings cannot describe an infinite God, who is a Being, not a human. This also describes a part of the sacrifice Christ needed to take, to become “like us”. John 1:14

So I won’t be edited out, I won’t comment on his chapter on God’s Body, but I think he’s stretching Biblical truths to lies. “What does the Bible say”, not, “What do we think it says.”

A good Orthodox Jew will disagree with your last statement.

LA Times April 26 1992 – three apartments burnt while observant Jews waited for the Rabbi to say it was OK to use a phone to call the fire department. Jews cannot use phones on the Sabbath.

Finally, Judaism is a way of life, combining theology and law. They have 10 primal commands, that “could be” summed up into one. (or two depending on interpretation) However, both they and Christianity are called to reveal God to the world. Christianity is based on Christ. The Gospel is based on what God has done to save us from His wrath. Christ’s primal command was “Repent”. A result of following that command is the “golden rule”. Otherwise you have a religion of works, not faith.

A very ancient idea made new again. For those interested, also check out Francesca Stavrakopoulou’s “God: An Anatomy,” an excellently detailed look at pre-biblical thinking of God – and the belief that He (God was a He back then) was absolutely a real being. And remains so through much of the Old Testament.