When the new reality of COVID-19 hit home at Valley Regional Hospital, Team Lavender, a peer-to-peer support team, heard the cry for help.

They put together a plan for formal debriefings at the Kentville, N.S., hospital but due to demands on the floor or at home, health-care workers found it difficult to leave their duties or come in for self-care. Consequently, Team Lavender returned to the drawing board and the “Wall of Hope” was born the first week of April.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

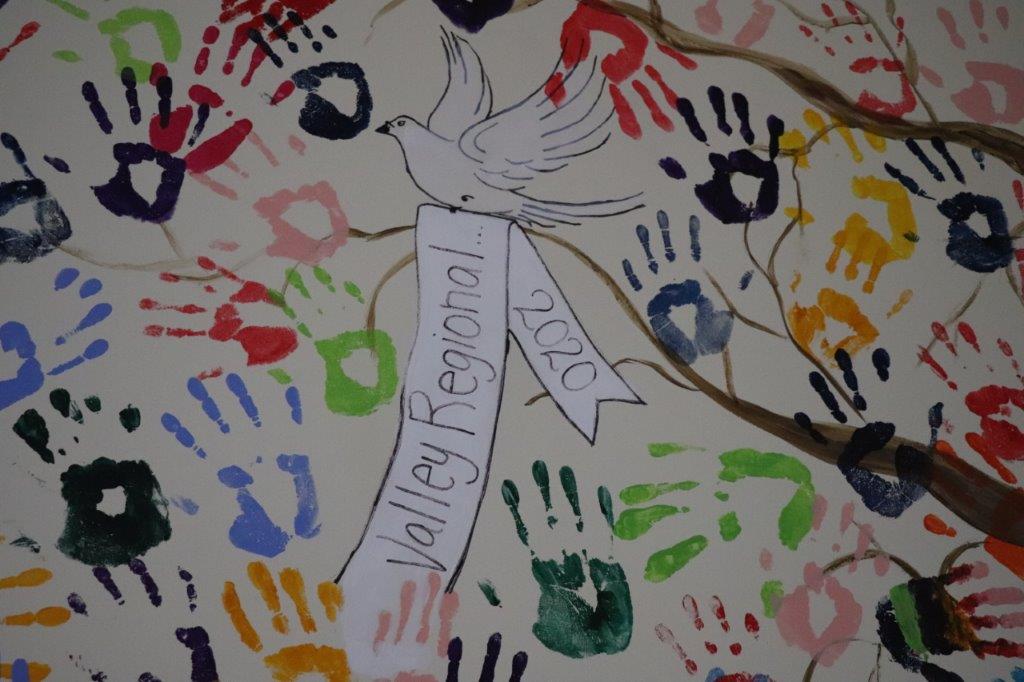

Two clinical nurse educators drew a huge heart on a blank wall in the hospital chapel, then they and a spiritual care coordinator painted their hands and left prints on the wall. When the floor nurses realized what was happening, they ran to the chapel to add their hands to the effort. Soon, there was a lineup down the hallway.

More on Broadview:

- Nova Scotia church restores beautiful hiking path

- ‘Christmas star’ to shine on winter solstice

- New Messiah production aims to lift up diverse voices

The Wall of Hope became a place for health-care workers to lament and yet celebrate one another and their family members. Some health-care workers whose life partners also work at the hospital wanted to paint their hands together on the wall, side by side. Others wanted to paint their hands on the wall with their working partners, while some wanted to paint each of their hands in a different colour, one representing them and the other representing their children.

The artists also painted two trees symbolizing the Tree of Life significant to some religions and cultures. A white dove sits in a branch on each tree, symbolizing hope, while a white ribbon held in the mouth of each dove weaves in and through the heart. The hands of many health-care workers are the leaves on the trees. Rainbow colours were chosen for the paint — Team Lavender wanted the Wall of Hope to represent as much of our diverse health-care family and the wider community as possible.

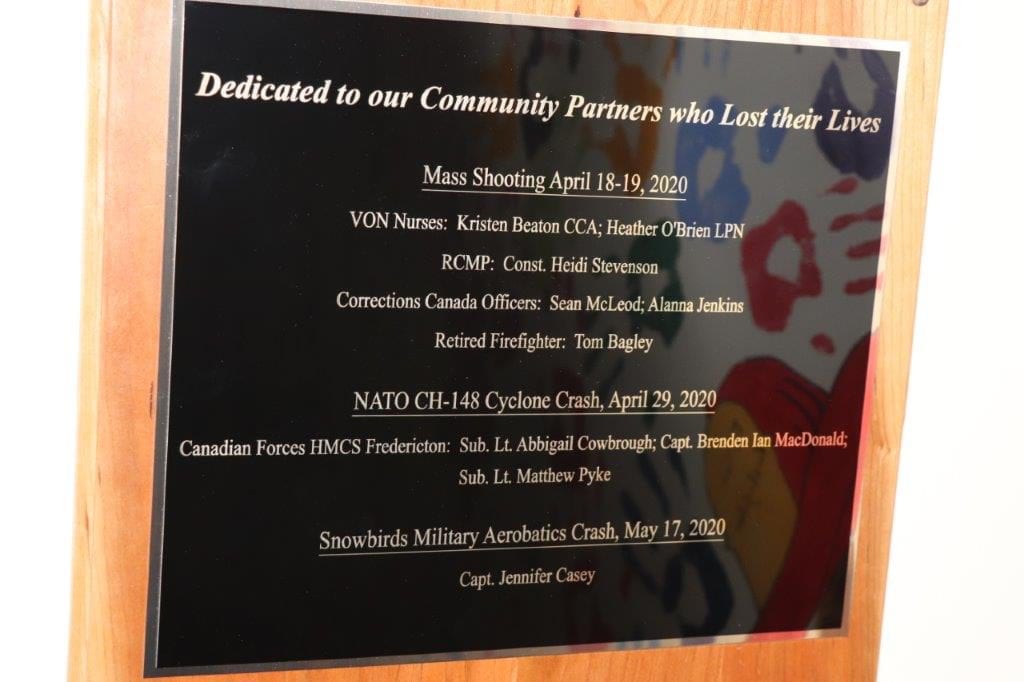

Tragedy struck Nova Scotia multiple times in 2020. Carrying all this pain in their hearts — many had connections to those who had lost their lives — health-care workers asked if we could incorporate our fallen community partners into the Wall of Hope. Among other tragic events this year, in April, a mass shooting left 22 people dead, including two Victorian Order of Nursing staff (community nurses who visit patients in their homes). The nurses who created the Wall of Hope painted symbols for the victims: a fire hat, a red maple leaf for our RCMP officer, two gold leaves for our correctional officers and two blue and white birds for the community nurses slain during the attack. More staff came to place their hands around the symbols on the Wall of Hope to hug those who had lost their lives, to thank them for their work and dedication and to let them know they would never be forgotten. Doctors from the emergency department donated a plaque that included the names of three Nova Scotians killed in April when their Cyclone helicopter went down off the coast of Greece, and the public affairs officer who died in May in a Canadian Forces Snowbirds crash. A helicopter and planes in formation were also drawn.

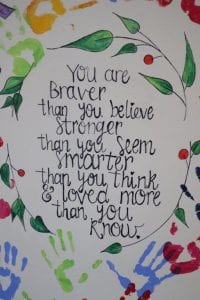

So why did this informal debriefing activity become so important to our health-care workers? It became a place where they could freely and safely shed tears expressing their pain and uncertainty. The Wall of Hope was also a place where health-care workers could share their stories with one another and find comfort in supporting one another. They could show appreciation for their working partners, as the realities of the pandemic forced many of them to reflect deeply on their own mortality.

As one health-care worker said, “I have never seen our hospital so united as it is now with the Wall of Hope.”

In my tradition, let me add, “Thanks be to God for gathering us in community so we could lament and find new hope in the midst of what felt like days of emotional and spiritual darkness.”

***

We hope you found this Broadview article engaging.

Our team is working hard to bring you more independent, award-winning journalism. But Broadview is a nonprofit and these are tough times for magazines. Please consider supporting our work. There are a number of ways to do so:

- Subscribe to our magazine and you’ll receive intelligent, timely stories and perspectives delivered to your home 10 times a year.

- Donate to our Friends Fund.

- Give the gift of Broadview to someone special in your life and make a difference!

Thank you for being such wonderful readers.

Jocelyn Bell

Editor/Publisher