There are over 50 versions of the Bible in English alone. Pull any two off the shelf, and it will be quickly evident that some are much heavier than others. A Bible’s weight doesn’t just depend on the size of typeface, the presence of commentary or the thickness of the paper. Some Bibles have as few as 66 books, others 81. Protestants traditionally prefer the slim ones; on average, they are about 152,185 words shorter than the Catholic versions. The additional books omitted from most Protestant Bibles are typically referred to as the Apocrypha (or in some circles, the Deuterocanon).

In its broadest sense, the term “apocrypha” can encompass all sorts of books that are not officially included in the biblical canon; so there are Old and New Testament apocrypha, as well as various other writings commonly called “pseudepigrapha” (meaning they were written under an assumed name).

Traditionally, though, when the word “Apocrypha” (with a capital A) is used, it specifically applies to 15 books containing stories, homilies, wisdom and apocalyptic literature written from roughly 420 BC to the early first century: Tobit; Judith; the Additions to the Book of Esther; the Wisdom of Solomon; Ecclesiasticus, or the Wisdom of Jesus, son of Sirach; Baruch; the Letter of Jeremiah; the Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Jews; Susanna; Bel and the Dragon; 1 Maccabees; 2 Maccabees; 1 Esdras; the Prayer of Manasseh; and 2 Esdras.

While the Apocrypha is not found in the Hebrew Scriptures (the Jewish Bible), most of the books are contained in the Greek version of the Old Testament, the Septuagint.

How did these 15 books find their way into the Greek Septuagint? The history is complicated. But sometime between 275 BC and 100 BC, in order to maintain their identity and heritage and because many didn’t read Hebrew, Hellenized Jews living outside Palestine began to translate Hebrew religious books into Greek. Hundreds of religious books were in circulation at the time, and from those, some (including all of the Hebrew scriptures contained in the Bible today) were translated into the Greek Septuagint. The Septuagint was the Bible read by most of the early Christians. It was also the collection of scriptures that New Testament writers used and referred to.

More on Broadview:

No one knows exactly when the Old Testament canon was finalized, but it is clear that after the rise of Christianity, the Septuagint or Greek Old Testament was rejected by the Jewish communities that remained in Israel. Perhaps to preserve their national language or to counter the groundswell of early Christianity, Jewish religious leaders tossed out the books whose source documents didn’t exist in Hebrew or that contradicted earlier biblical teachings. The Protestant Old Testament that we read today surfaced from this accepted Hebrew stream, while the rejected books eventually came to be known as the Apocrypha.

Whether the Apocrypha should be considered revelatory and authoritative has been hotly debated ever since. For centuries, religious authorities gathered at council meetings to determine which books should be deemed Holy Scripture. At each meeting, the list of “authoritative” books was determined by a majority vote, with a large minority of each council refusing to offer their stamp of approval.

By the time of the Reformation, two major biblical traditions were considered authoritative. The Greek Orthodox tradition adhered to the Greek Bible (containing the Apocrypha) and the Catholic tradition adhered to Jerome’s fourth-century translation into Latin, which also included the Apocrypha, although he made a distinction between it and the other scriptures.

During the Protestant reformation, Martin Luther rejected the Apocrypha, claiming that the books aren’t on par with the standard scriptures but “are useful and good to read.” To make his point, he separated the Apocrypha texts from the Old Testament scriptures and wedged them between the testaments, where they remain in some versions today. In response, Catholic religious leaders met at the Council of Trent in 1546 and officially recognized the Apocrypha as canonical. In versions of the Bible that reflect a high regard for the Apocrypha, its books are spread throughout the Old Testament.

For centuries, the word “apocrypha” (which literally means “hidden”) has been levelled favourably in an “It’s too good to be read” kind of way and in a damning “It should never be read” way. As the saying goes, beauty lies in the eye of the beholder.

Whether a Bible contains the Apocrypha and where it chooses to place it in relationship to the other texts reflects centuries of deep wrestling with what qualifies as Scripture and how we discern the voice of God.

Having so many Bible versions to choose from isn’t a sign of failure. On the contrary, it is testament both to the difficulty of the task of discerning God’s Word and the faithfulness of those who have pursued it.

***

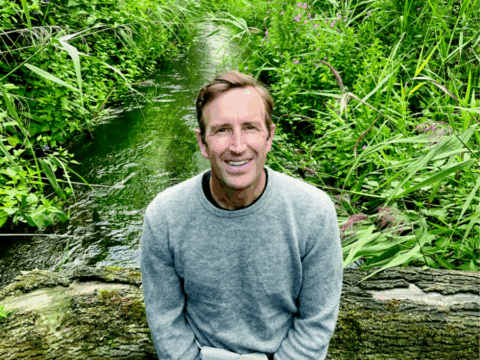

Rev. Trisha Elliott is Broadview’s Executive Director.

This is an excerpt from http://www.catholic.com, (Catholic Answers)

“With respect to sacred Scripture, the Apocrypha are those religious books written in the Old and New Testaments eras that claimed a sacred origin but were ultimately judged by the Catholic Church as not inspired by the Holy Spirit. These apocryphal books were thus excluded from the canon of Scripture, and yet in many cases retain some religious value.”

I find it interesting that there are still heated debates on why Catholic Bibles contain them and Protestant Bibles do not.

If we are to accept that our faith is based on Judaism, it would stand to reason that if Jews never accepted the Apocrypha as inspired by God, why would the Christian faith do so?