You were raised in a fundamentalist home. How did fundamentalism affect the early stages of your life, and how much sticks to you today?

A I never fully believed in the inerrancy of Scripture, but the solid rock of Scripture was always there. I really knew the Bible, and even today, no matter how rabid the fundamentalist, I can out-quote them. In fact, I do it in Greek — they don’t like that. I love the Bible; I read it daily. The other thing that has stuck is the feeling that being Christian requires decision-making. You can’t just “believe”; you have to do something.

Q You were a student teacher at Big Trout Lake residential school. There you encountered “the arrogant assumption that the White Man’s Saviour is the only way to save the world.” The theme of Christian arrogance is important for you. Why?

A It certainly had implications for Indigenous people and continues to be important in our relationship with other faiths, which tends to be arrogant and condescending — despite all our ecumenical talk. And [Christian arrogance] has implications for our attitude to the “great unwashed”; they, too, are part of the body of Christ, but our condescension makes us ineffectual at reaching them.

Q You were in parish ministry for eight years as an Anglican priest, but your description confuses me. Your language is warm, even wistful. But then you say, “I was thoroughly miserable.” Huh?

A I like to be close to people at great moments of their lives — birth, death and so on. Very few people are admitted, and it’s a great privilege. But I felt stifled by the institution, by my inability to say what was in the depths of my heart. Eventually, out of a conviction that the church needed renewal, I became attracted to training young people for ministry — only to find out that was an even deadlier job.

Q In the late 1960s, you moved out of big church into big media. What was that about?

A It was about getting out from under the ball and chain of the church. I went to New York to lecture in a seminary. All around me was noise, graffiti, people on the streets of Harlem. We in the seminary were completely out of touch. I wanted to learn how to communicate with that world outside. I wasn’t going to learn it at Wycliffe College teaching Greek. Journalism eventually gave me the freedom to say what I wanted.

Q That must have been a scary move. In the media, if they don’t like your stuff you don’t get paid. But in the church, you can preach clunkers week after week and get away with it.

A And they do. Oh, they do. Clergy get away with murder.

Q Are we doing any better today communicating with that “world out there?”

A Certain things in the social justice area are a witness. That’s important. But I wish the church spent as much zeal on theology as on social justice. The Anglican Church is moribund in its leadership and congregations. They’re caught in the past, not prepared to face the sacrifice of new thinking. The United Church is the same. They seem to be liberal, but in fact most of them are crypto-fundamentalists. When I was a journalist and needed a comment on a social justice issue, I could turn to the United Church and always get a headline-worthy reply. Today, I wouldn’t want to be charged with getting those headlines.

Q You’ve written a book called The Pagan Christ. What were you driving at with that title?

A A truly spiritual person never stops thinking about the implications of the christos because that’s one of the truly great archetypes of the human race. What I object to is the sense of monopoly, the sense that “the Christ” is only the Christians’ bailiwick. It is much bigger than that. Christos lives at the heart of the human psyche everywhere.

Q But you go further than most people. It’s one thing to establish “the clear dependence of the Christian narrative on early myth.” But then you make a leap, saying that Jesus himself is a mythical figure. Why do you need to do that? Even liberal thinkers like Borg and Crossan take the historical Jesus pretty seriously.

A Yeah, but they don’t offer a shred of historical evidence. Since my book was published, there has not been one scholar come forth with solid evidence from the first century, apart for a dubious reference in [the work of the Jewish writer] Josephus that they love to hurl around, a reference that is clearly, clearly, clearly false. I’ve been waiting for the evidence to show up. I don’t have a vested interest in there being no historical Jesus. I never set out to defend that position!

Q So why’d you go there? Nobody else does.

A No, but truth has a funny way of saying “What are you going to do with me?” There’s not a shred of evidence for a man called Jesus that historians would say was verifiable or legitimate. If someone has the evidence, I’d love to see it, because I don’t need the aggravation.

Q We all know atheism is the flavour of the day. But there are people who would say, “Harpur wants it both ways. He wants to ride the atheist wave but still call himself Christian.”

A People will say anything! If I sound occasionally like an atheist, it might be because the atheist is not all wrong. He or she might be a thinker. And that’s not encouraged in Christian pews. There’s such balderdash being handed out in churches every Sunday; it’s why I can’t go to church. It just makes me angry.

Q Your last chapter in your most recent book is called “Can Christianity be born again?” So, can it? And should it?

A Real rebirth means dying and being born to life again. There’s a lot that needs to die for rebirth to happen. But let’s look at it another way. If you have a view of Jesus as a concrete, historical person, it can be a block to your own spiritual growth. It begins and ends with that historical figure way back there — rather than realizing that the christos, the Christ, is the true inner spiritual self of every one of us. In the evolution of humanity, that’s what we’re straining for. What I like about fundamentalists is that they think there’s good news. They have a very weird idea of what that news is, telling you how loathsome you are in the sight of God; I lived with that in my youth, and I know what the guilt can do.

But the church can have better news than that. The church can tell you and me and the guy on the subway, “You have the Christ within you. You have the spark of the Divine in you. You are not just lovable; you are lovely. And you are meant to become love, meant to show love. You are meant to develop the Christ in you.”

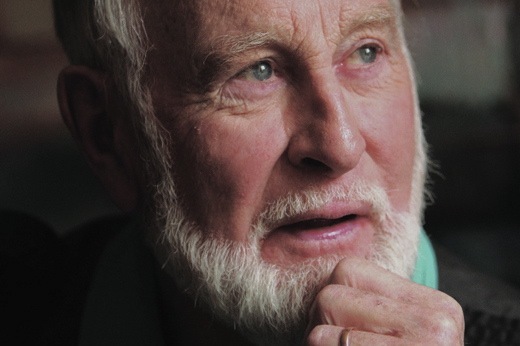

This story originally appeared in the June 2011 issue of The Observer with the title, “Interview with Tom Harpur.”