Tipis, signs, and flags have been a fixture in Regina’s Wascana Centre park, which is near from the Saskatchewan Legislative Building, since last winter.

However, on Sept. 7, after 192 days, the Justice for Our Stolen Children protest camp was ordered to leave the area, after a decision from a Court of Queen’s Bench judge in Regina.

The campers wanted to highlight the injustices faced by many Indigenous families, including the deaths of numerous Indigenous people, especially children, as well as the verdicts in the deaths of Colten Boushie and Tina Fontaine.

“I guess I was the one who called for the camp,” said core camper Richelle Dubois. “There were four of us that started that day, we put up two tents, and started the sacred fire on Feb. 28 by noon. We’ve been here pretty much ever since.” The camp grew. At one point, 15 tipis were set up on site.

Many campers were there because they had either experienced tragedy firsthand, like Dubois, or because they know someone who lost a child, a sibling, a parent, or a friend.

“I believe that we’re a platform for other families, to have their voices heard and get some help from the camp in regards to dealing with social services and the injustices in the system,” Dubois said.

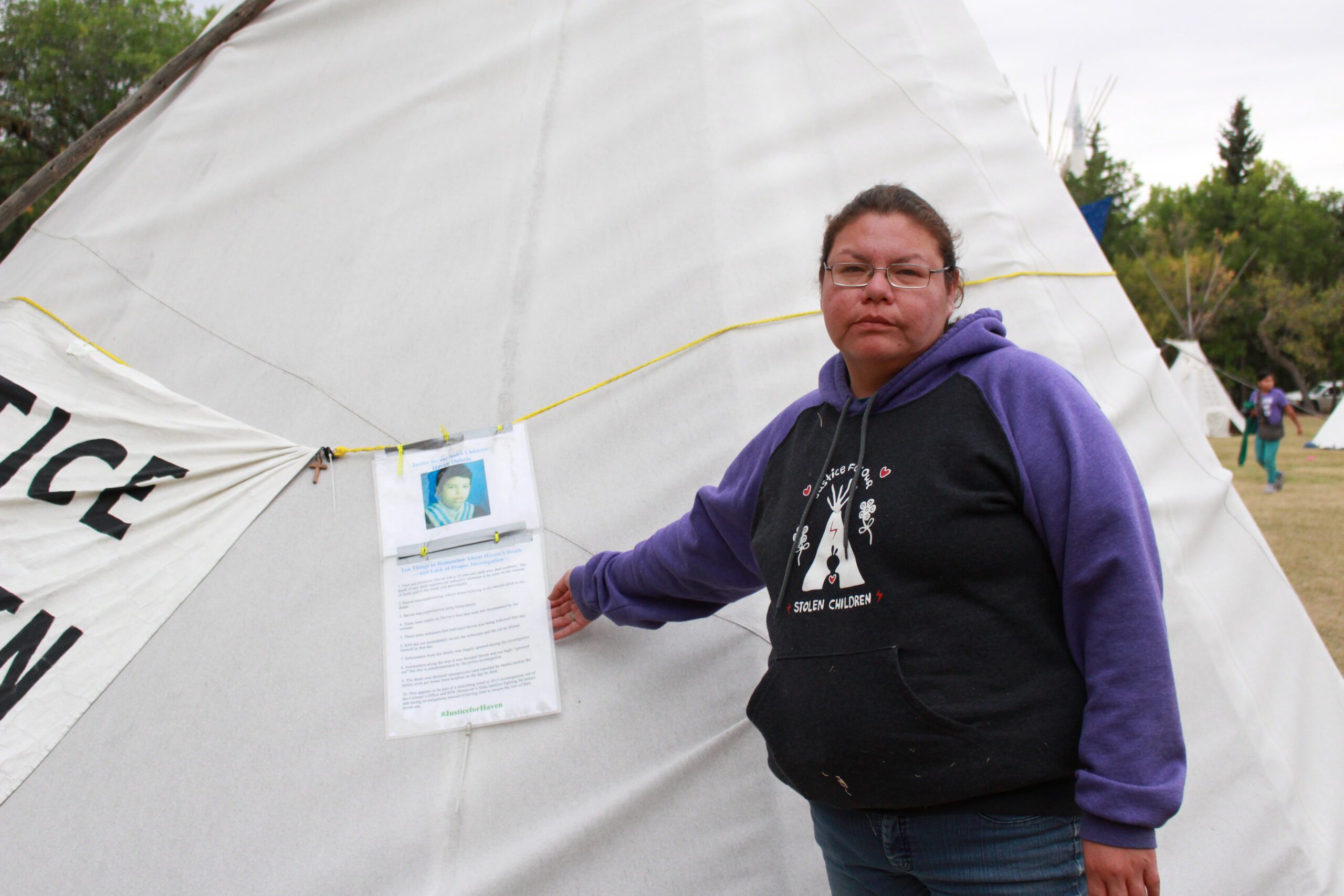

Dubois’s son, Haven, died in 2015 at 14 years old. She said the police investigation into his death was “shoddy at best” and that there were multiple errors.

According to Dubois, some of the errors included not documenting an injury on his face, and a mistake in the police report of the way his body was lying when he was found, which Dubois said she knew, because she was the one who found him.

However, she said police didn’t take her statement that day, or any day after. The police ruled his death an accidental drowning with marijuana being a significant contributing factor. Dubois said it was deemed non-suspicious before she even got home from the hospital.

After the police didn’t answer her concerns about the investigation, Dubois camped outside the Regina Police Service for three nights. She was eventually allowed to see the report, and went through to find claims that she said didn’t have enough evidence behind them – like the presence of marijuana in her son’s system. She’s still looking for answers as to what really happened to her son.

In August 2016, Colten Boushie, a 22-year-old Cree man, died in a shooting incident on Gerald Stanley’s farm. In February, Stanley was found not guilty of second-degree murder by a jury, sparking outrage across Saskatchewan and Canada.

The February verdict in the death of Tina Fontaine caused similar outrage when Raymond Cormier was also found not guilty of second-degree murder. Fontaine was a 14-year-old Indigenous girl whose body was found in the Red River in Winnipeg in August 2014.

“I think the reason why it matters that we’re here is that we’re in direct opposition to the policies and procedures happening across the street at the Saskatchewan Legislative Building,” said Robyn Pitawanakwat, another member of the camp. “Being here is a constant reminder to them that we know that they’re not doing the job they claim to be doing.”

The camp’s presence also shows families who have been “victimized by the system” that there is an alternative to colonial structures, she said. “When people see tipis, they know that it’s going to be a very different setting than a brick-and-mortar storefront.”

In an emailed statement, Central Services Minister of the Government of Saskatchewan, Ken Cheveldayoff, said the government is pleased with the Court of Queen’s Bench decision, and they “expect the Justice for our Stolen Children Camp will abide by the Court Order and remove the tipis and other structures from Wascana Centre within a reasonable time.”

Legal council for the camp, Dan LeBlanc, said the camp’s position throughout the case was that the government can’t arrest its way around the issues. The camp was briefly dismantled in the middle of June, when six protesters were arrested for obstruction of justice when they refused to abide by a police request to leave. No charges were laid.

“They’re out there raising serious issues which fundamentally concern matters of reconciliation and justice,” said LeBlanc of the campers. “From the camp’s perspective, rather than addressing those issues, [the government is] just trying to make them go away.”