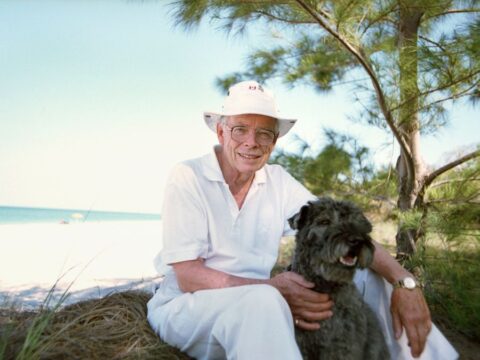

Alan Bowker, a historian who spent 35 years in Canada’s diplomatic corps, has dedicated the past 10 years to uncovering the untold stories of Canada’s soldiers. His latest book, A Church at War, follows an Ottawa United Church congregation that sent 141 members to fight in the First World War, with 19 never returning home. It also marks the 110th anniversary of the war’s onset on July 28. Historian and United Church minister Rev. David Kim-Cragg spoke with Bowker about the importance of bringing these stories to light.

David Kim-Cragg: What first got you thinking about writing this book?

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Alan Bowker: I’m a member of MacKay United Church in Ottawa. Every year at Remembrance Day, we have a service where we read out the names of those who died. Tim Cook, a leading military historian, is also member of our congregation. He came up to me after the service in 2014 and told me that Library and Archives Canada was putting the attestation papers and some of the military records online, meaning it would be possible to find out who these people were, beyond just their names.

For the next five years, each Remembrance Sunday, I presented the congregation with the stories of the people from the church who had fallen 100 years before. But it wasn’t enough just to talk about their military record and how they died. I got hooked and started digging deeper: Who were they? What about their families? What about the church? And the people who served and came back?

At the time of the First World War, our church had 369 members and maybe three times as many adherents. It sent 141 people off to fight. This is an astonishing record, but it’s not unique. You can go to churches and communities across Canada and find the same thing.

DKC: With all of the information you found, through physical documents and online, what kind of picture has emerged?

AB: It’s the story of a single church’s experience of the war, as well as the story of how 19 individuals and their families experienced the war. It’s history from the bottom up. It’s the story of people who are otherwise forgotten.

The congregation of MacKay church, like most other Protestant churches, was convinced that this was a just war; that they had a duty as Christians to take up arms to punish German aggression; and that those who fell had — in the words of a plaque they erected after the war — “made the Supreme Sacrifice … in defence of justice, truth, and righteousness, and for the Glory of God.” Intertwined with this was a strong sense that Canada and the Empire also stood for these things, and had to be defended. There was also a tradition of athletics and military service which the church encouraged — or “manly Christianity.” So, you roll all those things together, and you have a strong motivation for people to join the cause. But you can’t know what everybody who sat in the pews thought.

Meanwhile the women saw themselves as good Christian wives and mothers. But they were also beginning to see themselves as having agency in areas like prohibition and in actively supporting the war. It’s an interesting sort of transitional period. And of course, in 1917, these women get to vote for the first time as mothers and sisters of soldiers.

More on Broadview:

DKC: How has the meaning of Remembrance Day changed for your church since you started researching this book?

AB: I think one of the most heartening things about writing the book was the feedback I received. I got the sense that what I was doing transcended the simple writing of history; that bringing these people to life, seeing who they were, telling their stories and travelling to a distant world of the past was not just an intellectual exercise. It was essential to the understanding of why Remembrance Day is important.

These aren’t sons or brothers or fathers of the living anymore. But the presence of these families, who sat in these pews, is still in the church, in our DNA. The past is not a foreign country, it’s our country. That world became our world. And although there are many things about it that are different, there are many links that join them to us.

Ultimately, it’s the sacrifice, courage, resilience, dedication, faith and hope that transcend time.

DKC: Do you think that in the Canada we live in today, the MacKay United members from a more than century ago would recognize things they thought they were fighting and dying for?

AB: It would be unfair to expect them to fully accept our world in the same way that it would be unfair to expect us to fully accept their world. It’s a two-way street. I suspect that they would probably be gratified at the fact that there is a Canada, and that it’s diverse, welcoming and tolerant. The Canada that is talking about reconciliation, that honours diversity and inclusion would not have been theirs. But it’s the Canada at whose roots they lie. It is their Canada.

DKC: Of all the personal stories you tell in your book, was there one that has stayed with you, haunted you, or that you find yourself thinking about more than others?

AB: In some cases, the stories of the soldiers are less interesting than the stories of their families: like a mother-in-law going to court to rescue her children from a greedy second wife; or a mother who, having lost her husband, responds by basically abandoning her children to run off with another person. Those are fascinating stories. But so are the ones about a soldier going on a suicide mission to stop a German advance. Or a great Ottawa athlete who got shot down in an air battle.

DKC: I get the feeling that this book was a personal journey for you. How did researching and writing it change you?

AB: I learned from writing this book that “lest we forget” means lest we forget those people, who they were and what they did for our country.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

***

Rev. David Kim-Cragg is a historian, author and minister at St. Matthew’s United in Richmond Hill, Ont.