The tearful shaking came when I was alone in an elevator. It didn’t come when the judge ruled that I was to become the guardian of “J.” It didn’t come when J and I hugged outside the courtroom. It came a week later after I delivered the document that released the public guardian from her duties and made me the permanent guardian for this adult with disabilities.

I was weeping for the long 18-year journey of pain, emptiness and adjustment since our son Josh died from cancer at 16. I was weeping for Toby Boulet, a teaching colleague whose son Logan, who went to Sunday School in our church, was killed in that horrific bus collision in Saskatchewan. And I was weeping for J himself, 49 years old with little family contact, on government support due to a medical accident when he was six months old, leaving him with a unique cluster of disabilities and strengths.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

For eight years I worked 15 hours a week for an agency as a caregiver for J. I knew what my responsibilities would be: oversight of his 24-hour care and his well-being. J is on multiple medications, can’t move as fast as we do, has memory problems and will probably have a life span 20 percent shorter than the Canadian average.

But he is cheerful, friendly and socially skilled. He likes doing volunteer work and crafts. When people meet him they like and remember him. He has the ability to be in a social setting and knows what to say, and what not to say. He can read faces very well. He proved it in court by answering questions from the judge in a straightforward way without embellishment or distraction — unlike so many non-disabled people who don’t know when to stop talking.

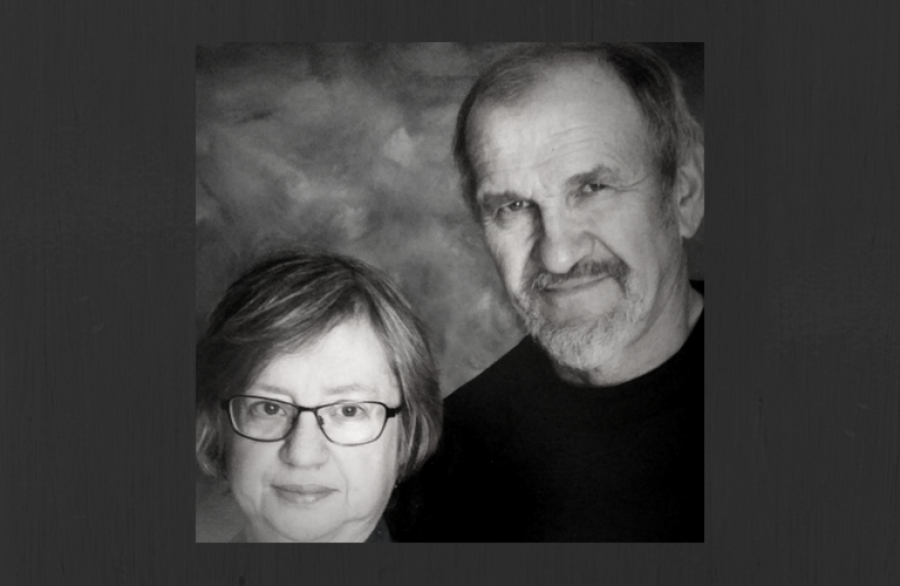

J is very appreciative of the help we give him. His Christmas card to my wife, Sandy, and me said: “Thank you for being my dopted parents.” As I think of the word parents right now, I again feel the emotional seizure of tears. When your only child dies at 16 there is no graduation, no wedding, no grandchildren. Being Josh’s father was the most natural thing I’ve ever done. But I can extend my fatherhood to help J as his guardian, more than I could when I was his worker.

Matthew 25 says: “the least of these my brethren”. I interpret that as if we can help, we must help. I have seen disabled adults show sensitivity and kindness to other disabled adults – for those who cannot speak at all or for those in wheelchairs forever. Given the right individual, you would find he or she gives you purpose, teaches you and elevates you.

In the eyes of God, we are all disabled. J, with his imperfect grammar, once made a statement of clarity and power we should adopt for ourselves: “I am a disability.” So many of us are disabled with addictions or with tragedies that wound us forever. We disable and pollute the earth. Our search for justice and peace is disabled by foolish leaders and criminals. But there are acts of intelligent kindness that manifest saintliness. Logan Boulet, for example, signed his organ donor card a month before he died, and now six people have better lives.

When our son was in his last months of life, he told us “I want you two to go on.” J is not Josh Wilson, but if we can help the least of my brethren, we must do it. Logan and Josh would like that.