At 6 p.m. every Thursday night, Rev. Ingrid Hartloff Brown nestles into the fort she built at home with her children, ages nine and 11, and turns on Zoom. Staring back at her are the faces of about 20 other children and youth from her congregation at St. George’s United in Courtenay, B.C.

During Fort Fellowship, she hears about their joys and sorrows, reads them a story, sings with them and prays with them. It’s a children’s vespers, Hartloff Brown explained. She launched it just after the COVID-19 pandemic shut down in-person church in March.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

“I’ve been struggling with how much Sunday school-style teaching I am trying to get into them, versus how much relational time,” said the quarter-time minister of children, youth and families. “It has been so relational. Thursday is about being together and hearing prayers, hearing about their dog, or their cold. We got to meet a newborn baby one night… If the kids walk away from this with fewer Bible stories but the sense of being loved and belonging, I think the church is working.”

Like faith leaders across the country, Hartloff Brown had to quickly figure out how to minister to young people she could no longer gather together. While many summer camps ran day programs this year, and some congregations hosted in-person vacation Bible schools, none of those came with the added concern of mixing young people who may be back in school this fall with elder and immunocompromised congregation members.

Now that September is approaching – the month churches usually relaunch programs for young people – congregations and families are swiftly reinventing Sunday school with mostly-untried virtual and in-person programs. However, reframing faith formation may be exactly what the church, families and children needed.

More on Broadview:

- Children’s Bibles are North America’s unlikeliest publishing success story

- Tender new memoir explores life as a preacher’s wife

- COVID-19 puts kids’ church camp fun on pause

Choosing a path forward can be overwhelming.

“Looking for resources for homeschooling and church is like trying to take a drink from a fire hydrant,” said Hartloff Brown. “When we made the decision to do Fort Fellowship, it was a decision to not try to do ‘all the things.’”

St. George’s started with the goal of maintaining relationships and extending care, until the church can meet again. In nearby Cumberland, Hartloff Brown is also the three-quarter-time minister at Weird Church, a church plant for “spiritual refugees” and folks who never thought they’d enter a church. Nearly a quarter of regular attendees are children and youth, and the median age is about 40, she said. They’ll start meeting again in September, with an in-person, online-hybrid worship – easier to do than in a mostly-elder congregation.

Hartloff Brown also argues that families can overlook themselves as the biggest influencers of children’s faith formation.

“I hope the pandemic encourages parents to take more initiative in their religious at-home education,” she said.

Children’s absence from church buildings didn’t begin with COVID-19, pointed out Marlys Moen, the pastor at Mount Zion Lutheran Church in New Westminster, B.C. Her denomination started creating resources for families to teach their children at home nearly 30 years ago, when children’s Sunday attendance dropped off due to soccer, parents’ work and other tasks. Nearly 500 years ago, Martin Luther wrote the children’s catechism that Moen was raised on, with the idea that fathers should take responsibility for faith formation in the home.

“The most powerful teaching always happens at home,” she said, noting that the pandemic is a perfect opportunity for families to take on more responsibility – though the church should still play a central role.

To keep children involved in Mount Zion’s intergenerational online worship, she has continued asking them to read scripture, light candles and say the dismissal. The congregation’s two-year confirmation program for ages 12 to 14 has continued sporadically online. Mount Zion does not plan to worship again in person soon.

Resources that can help

An increase in homeschooling is expected this fall, given safety and other concerns in Canadian classrooms, so parents will likely be searching for educational resources for their children that line up with their values. Just in time, the ecumenical justice agency KAIROS Canada launched Ravens: Messengers of Change this July. It’s a free multi-age program from the organization that created The Blanket Exercise.

“It’s a gentle way for families looking to take on Indigenous rights in Canada to dip their toes in the water,” said KAIROS Canada’s Indigenous rights program coordinator, Chrystal Desilets, who designed the resource. An Indigenous tattoo artist drew the illustrations, which children can colour in, she said.

Given that COVID-19 has coincided with activism around Black Lives Matter, the Wet’suwet’en pipeline protests and other critical anti-racist events, the Pacific Mountain Regional Council Archives’ new study guide for children and youth about the Japanese internment in B.C. is timely.

Parents and church leaders may also wish to show young people “The Children Remembered” website – General Council’s archive of photos and stories detailing each of the residential schools the United Church ran.

A chance to reflect on purpose

Parents, of course, shouldn’t be alone in teaching faith to their children; faith leaders are equipped to help children metabolize their grief, wonder, fear and hope coming out of this pandemic. So Jeffrey Dale was shocked when clergy and lay leaders were not on the list of “essential workers” the government of Ontario rolled out in March. He’s the minister for faith formation, youth and young adults for Shining Waters Regional Council in Ontario.

“How do we work our way back to being essential?” Dale asked. “To be blunt, the pandemic has given us the opportunity to ask whether we want to go back to the same programs, engaging the same kids. How do we use this time to reflect about what the community’s needs of us are?”

In ministry with young people, Dale said, the church has too often substituted fun and games to drive up attendance numbers, without reflecting enough on whether the programs meet the needs of those who are present — or absent. Children and youth, he said, struggle with the same things adults do: poverty, marginalization, and the question of whether their own lives matter, and why.

Dale organized virtual Sunday school for children in his region from April to June, and engaged about 25 young people each time – representing, he said, less than five percent of Sunday school members. It was helpful for children from smaller congregations especially, he said, as they get to meet other church kids. But what they really miss is being together.

Alongside the busyness of restructuring programs to meet safety requirements, Dale said he hopes leadership really pauses to ask what young people in their communities need of them, and “build back better” with that in mind.

“We are a society that is hungry for figuring out meaning,” he said. “The meaning of Black lives. The meaning of Indigenous lives. What is the place for all of us in society? The church needs to be the space where people can carve out meaning.”

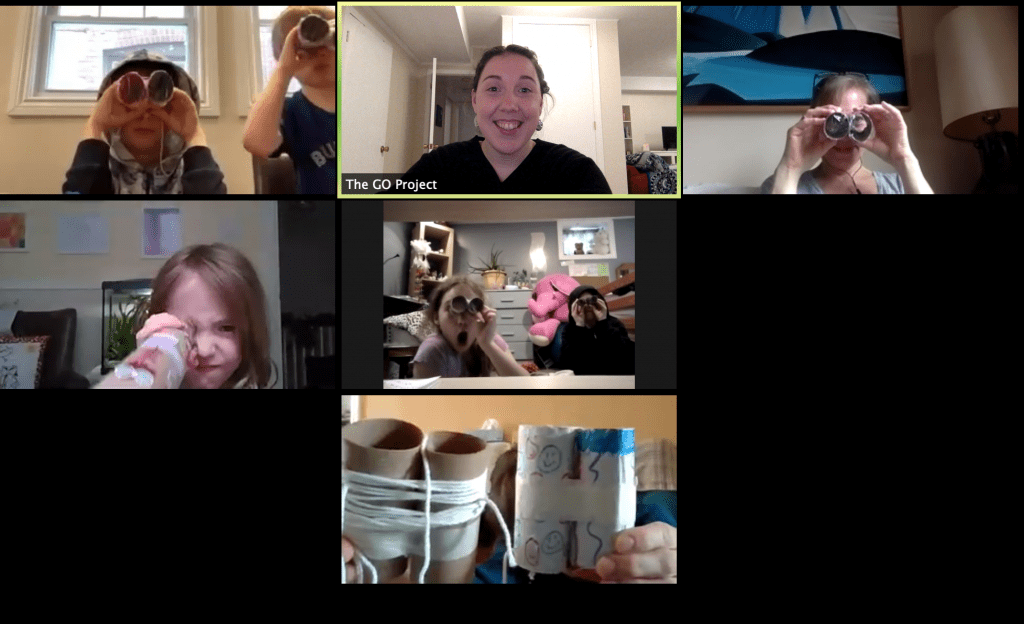

To help meet those needs, in Toronto, Alana Martin spent the summer transforming The GO Project’s youth social-justice curriculum into a weekly Sunday school curriculum that can be delivered virtually, socially-distanced or in-person, and will be sold through United Church Resource Distribution. Martin, the minister to The Go Project, has plenty of experience test-driving online learning for churches. She has three pieces of advice.

“You have to be flexible,” she said, noting that you never know if 20 kids or one kid will appear.

Be mindful of one-on-one situations, and children who Zoom from their bedrooms, said Martin. “Encourage them to be in a common space such as a table. And if just one child shows up, make sure there’s a second adult on the call.”

Finally, just do it. “I think people will forgive us if we try something for a year and it’s imperfect – but with the goal of being what communities actually need,” she said.

***

Pieta Woolley is a journalist in Powell River, B.C.

I hope you found this Broadview article engaging. The magazine and its forerunners have been publishing continuously since 1829. We face a crisis today like no other in our 191-year history and we need your help. Would you consider a one-time gift to see us through this emergency?

We’re working hard to keep producing the print and digital versions of Broadview. We’ve adjusted our editorial plans to focus on coverage of the social, ethical and spiritual elements of the pandemic. But we can only deliver Broadview’s award-winning journalism if we can pay our bills. A single tax-receiptable gift right now is literally a lifeline.

Things will get better — we’ve overcome adversity before. But until then, we really need your help. No matter how large or small, I’m extremely grateful for your support.

Jocelyn Bell

Editor/Publisher