It was the buttons that got him. Bruce Douville otherwise knew what to expect at the Student Christian Movement’s general conference last May. It was all on the agenda: anti-oppression workshops, discussion panels on the conference theme (“Queer and Christian without Contradiction”) and plenty of spontaneous singing. But the buttons, handed out and worn on backpacks and jackets, perplexed him. They bore a familiar image, Alberto Korda’s portrait of Che Guevara, morphed into a likeness of Jesus Christ.

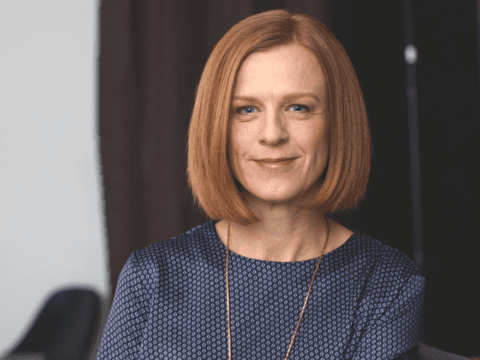

Though not a member of the Student Christian Movement himself, Douville has been studying the relationship between religion and radical politics for his PhD at York University.

And he could not ignore the buttons. “If somebody uses the word ‘revolutionary,’ who comes to mind?” he asked me weeks later. “If you surveyed 100 random people on a street corner in Toronto, I expect a number of them would identify Che. How many of them would identify Jesus? Next to none.”

Members of the Student Christian Movement of Canada (SCM) would. Since 1921, the SCM has questioned traditional interpretations of Christianity, advocated for union rights at the height of McCarthyism, protested the war in Vietnam and fought for nuclear disarmament. Most recently, they’ve campaigned in and out of churches for inclusiveness of all sexual orientations and gender identities. In every decade since its inception, the SCM has challenged campus stereotypes of the faith-based student group. Recently, though, this mission has proven to be increasingly difficult as church pews grow empty, student populations shift and interest in faith-based ventures of any kind declines.

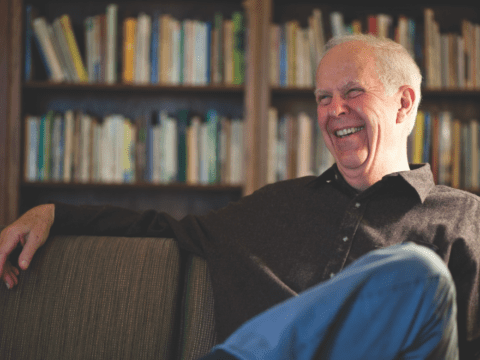

When the SCM got its start in Canada, finding new members wasn’t a problem. With the embers of the First World War still cooling in the early 1920s, students wanted to distinguish their values from those of their parents. “There was a trend of wanting to have stability, to resurrect peaceful ways of living,” says York professor Stephen Endicott, an active SCM member while a student in the 1950s. His father, Rev. James Endicott, co-founded the SCM while studying at the University of Toronto in 1921.

Faith values were shifting, too. The students with whom James Endicott felt a kinship weren’t interested in the Jesus who saved souls, but the Jesus who fed the hungry, healed the sick and encouraged others to do the same. Stephen Endicott cites the rise of the social gospel and increasing awareness of global injustice as reasons why students wanted a place where they could wrestle with world issues that had not reached the pulpits.

Mistrust for authority — from government to church leaders — had also begun to sprout among North American adolescents. Says Endicott: “There were disparities between those who profited from the war and those who did the dying. Students were very aware of this.” While the SCM continues to foster many of these same values today, it does so in smaller numbers — a decline Douville and others have traced back to the 1960s. Though Canadian membership records are casual at best, Richard Allen, author of The Social Passion, estimates that the first SCM general conference in Canada drew over 1,000 people. This year’s conference drew 40. In his research, Douville has also noted that nearly five percent of the student body across English Canada was SCM-involved up to the 1930s. “It was pretty much the only social justice organization on campus,” he says.

From then to now, walking the line between being a politically active and faith-based group hasn’t been easy, especially when much of the SCM’s work clashes with traditional church doctrine. In the earlier days, members were widely thought to be a bunch of Bible-doubting, Communist rabble-rousers. Some professors and parents accused them of “poisoning the student mind.”

But the SCM has always been dogged by negative stereotypes and stigma. SCM co-ordinator Beidy Cassas-Arragon recalls a recruiting fair for University of Toronto campus groups last March. Ardent supporters of sex-ed rights, SCM members had bowls of condoms displayed at their information booth. It confused some (“But aren’t you a Christian group?”) and annoyed others, who didn’t believe a faith-based group would genuinely support safe sex. Some took condoms and pulled them apart to “test” them for efficacy.

At the same time, other students just aren’t interested in joining a group that aligns itself with religion, even if the social justice aspect appeals to them. Historically the SCM has always welcomed people of all faith backgrounds and currently boasts a number of atheists and agnostics among its members. You don’t even have to be a student to join. Still, public perception about religious organizations was summed up in the reaction Douville got when he told a friend he’d been to a conference where he hung out with a bunch of “radically left, queer Christians.”

“Ew,” said his friend. Douville later wrote about the conversation on the SCM’s blog: “I’m quite certain that it wasn’t the ‘left’ or ‘queer’ thing that made him feel icky. It was the ‘Christian’ thing.”

Religion and politics aside, there may be other reasons why student interest isn’t what it once was. The general decline of liberal church membership is an obvious obstacle. The explosion of student groups — any campus can have upward of 50, many of them also focused on social justice — can’t help either, nor does the schedule of your average Canadian student. A recent study estimates close to half of all Canadian full-time students work jobs. Also, many campuses have become largely commuter based. The Winnipeg SCM unit often struggles because “people just go home after class,” says David Ball, general secretary of the SCM.

In the long run, though, numbers may not prove to be all that important. Ball points out that the group has always operated by attraction, not promotion. He got involved after attending a national conference in 2003 as a first-year student and liking what he saw. “It was exciting to be part of something with all these people who were looking for more than the same old activist package.”

After the conference, Ball launched an SCM unit at the University of Victoria, starting with a weekly potluck liturgy. The reaction was immediate, and people started to join. “The campus hadn’t seen anything like this before,” says Ball, who was also involved in setting up a new SCM unit at the University of British Columbia last February.

SCM alumni are known for their leadership and outspokenness. James Endicott became a United Church minister who sparked controversy by openly supporting the Chinese Revolution and criticizing the United States during the Korean War. Very Rev. Lois Wilson became the first female moderator of the United Church. Jack Sword was a president of the University of Toronto. It’s little wonder, Douville points out, that “a lot of people who got political got their start in groups like the SCM.”

And sometimes, rather than sparking political aspirations, the SCM inspires the spirit. Both Douville and Ball recount an event from this year’s general conference they won’t soon forget. After a lot of reflection, one of the group’s national representatives decided he wanted to be baptized. His involvement with SCM led him to consider the ministry — a world away from studying dentistry — and baptism was how he wanted to start that journey. Drawing labyrinths in the sand, singing hymns and laying hands, the entire group then watched as one member baptized the other in the waters of Lake Ontario, off Toronto’s Centre Island. It was windy, it was cold, but according to Douville, it was also “one of the most personal and moving baptismal experiences I’d ever seen. For him, SCM was how he reconnected with his faith.”

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s September 2009 issue with the title “Faithful to the cause.”