Since 1875, the little wooden church sat amid wild prairie grasses, withstanding blizzards and ferocious lightning, as well as the warm chinook winds that blew in from the Rocky Mountains to the west. It had been built by Methodist missionaries who ventured here from Ontario to convert and “civilize” the local Indigenous people.

By the early 1950s, the church had long been abandoned and was falling apart. That’s when some United Church faithful in Calgary stepped in and restored it to its original state. Over the years, McDougall Memorial United Church became a familiar marker for those travelling the original Trans-Canada Highway that winds between Calgary and Banff, Alta., and a popular spot for weddings and tourists. Twice a year, a special service was held to commemorate the founding of the mission among the Stoney Nakoda people.

One night in May 2017, the church went up in flames. The RCMP deemed it an act of arson, but no one has been charged.

Now members of a historical society, run by a descendant of those Methodist missionaries, are resurrecting the church on its original site just outside the boundaries of the Stoney Nakoda reserve. They describe the project as an act of reconciliation, a way to mend a broken relationship. But the elected Stoney Nakoda chiefs and councillors don’t see it that way and have fought their plans every step of the way. In their eyes, the new church is a painful symbol of colonialism cloaked as religion — a monument to an era when evangelizing Christians were the vanguard of a devastating upheaval of life as they had known it. That upheaval still reverberates today and is at the heart of the story of the little church.

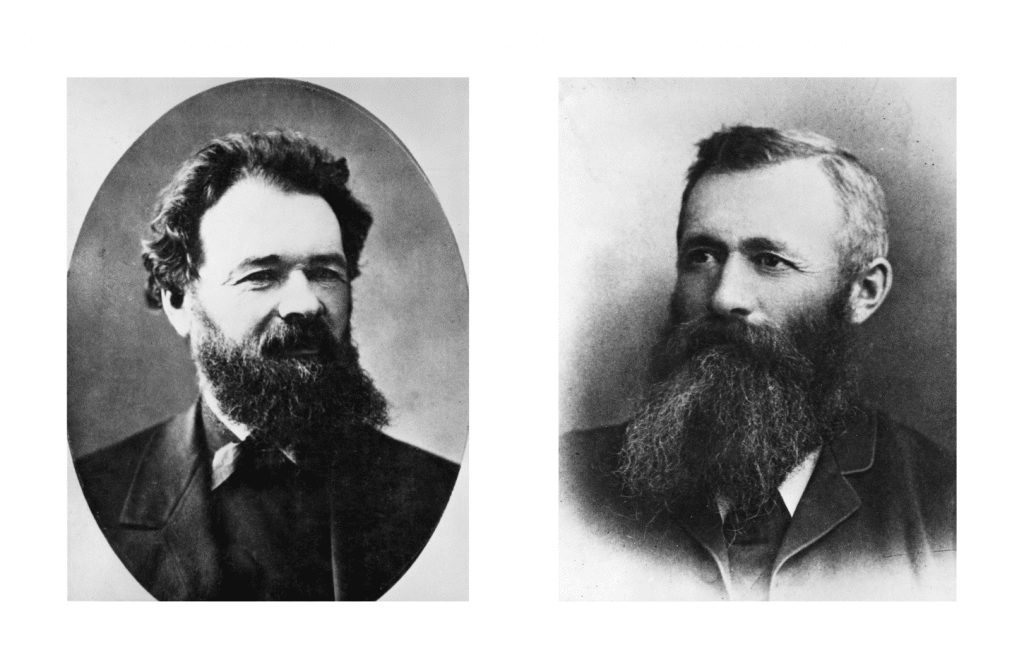

Rev. George McDougall arrived in what is now southern Alberta in 1873, together with his wife, Elizabeth, their sons John and David and their families, some friends and a herd of cattle. The McDougalls had trekked there to establish a Methodist mission. No other white settlers lived in the area, but there were plenty of Stoney, Tsuut’ina and Blackfoot people.

The McDougall clan set about building a rudimentary fort on a hill not far from the Bow River and the Rocky Mountains. Two years later, they moved the mission closer to the river and built houses, barns, a trading post and a church. When George died during a blizzard in 1876, his eldest son, John, was more than ready to follow in his father’s footsteps. John named the mission Morleyville, after the Methodist minister who ordained him. This was Stoney territory, but the Stoneys didn’t resist and, according to John’s written accounts, were intrigued by both the newcomers’ religious practices and their trade goods.

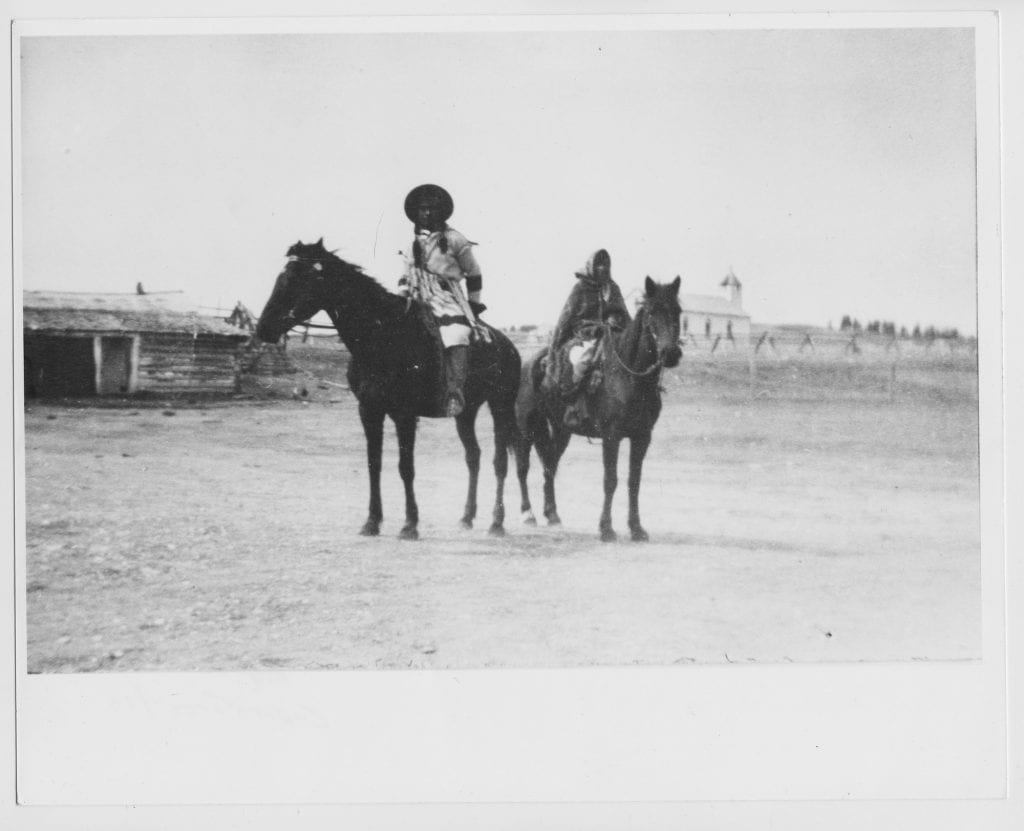

Rev. John McDougall was as much an adventurer as he was a devoted Methodist. He could chase and shoot buffalo from horseback just like the Stoney and Blackfoot people. Journeying across the western plains and foothills, he stayed for long spells in Indigenous camps, conversing with Elders, dispensing medicine, settling disputes and delivering sermons in fluent Cree, which he had learned as a young Methodist missionary in Manitoba. (Most of the Stoneys spoke their own language, but many of them also spoke or understood Cree because they had close ties to Woodland Crees in the northern part of their territory.)

McDougall established strong bonds with the Stoneys and admired what he saw as their Edenic way of life. He encouraged them to keep practising their own spiritual beliefs as well as Christianity. But he was also a fervent believer in the Victorian idea of progress. As he travelled the prairies, he was constantly looking for good townsites and development opportunities. As he wrote in one of his many books, “I was locating homes and selecting sites for village corners, and erecting schoolhouses and lifting church spires, and engineering railway routes, and hoping I might live to see some of this come to pass, for come it would.”

One of McDougall’s projects was an orphanage and training school where Stoney boys could learn how to be farmers, and girls could learn domestic skills. Established in 1883, it housed about 45 children by 1901. Some children may indeed have been orphans, but many were not. In 1905, according to a United Church history, a principal who allowed children to go home for weekly overnight visits was removed, which led to a revolt by parents. The school closed in 1908, beset by money problems, truant children and resistant parents.

In 1968, almost 100 years after the McDougalls established the Morleyville mission, Rev. John Snow was elected chief of the Wesley band of the Stoney Nakoda Nation, a position he would hold for 28 years. Snow was the first Stoney Nakoda to be ordained as a United Church minister. But in a book published in 1977, he disparaged John McDougall as having betrayed the goodwill of his people. Snow pointed to documented evidence that McDougall was acting as an agent of the federal government while he was advising the Stoney Nakoda to sign Treaty 7, in which they agreed to give up their territories in exchange for a much smaller reserve. “All this time we thought the missionaries were making the best possible deal for us, but in fact they were working to secure land for white settlers,” Snow wrote in These Mountains Are Our Sacred Places.

According to Snow, the Stoney chiefs who signed Treaty 7 in 1877 believed it was a peace treaty in which they simply agreed not to attack or harass the growing number of cattle herders and settlers who were moving in. But they soon found out they hadn’t signed a peace treaty. “If my forefathers had known what all this would mean to our people: the disappearance of the buffalo and diminishing of other game, the restrictive game laws, the plowing and fencing off of all the lands, more whitemans’ diseases, attacks on our religion, culture and way of life, the continual eroding of our other treaty rights; if they could have foreseen the creation of provincial parks, natural areas, wilderness areas, the building of dams, and the flooding of our traditional hunting areas, they would never have signed Treaty Seven. But they relied on the missionaries who said, ‘The Queen’s government will honour the promises in the treaties,’” Snow wrote.

Despite his antipathy toward the early Methodist missionaries, Snow hoped that being a United Church minister meant the denomination would help him secure better medical services, education, housing and economic development for people on the reserve. He was deeply disappointed. “It didn’t seem that the Church really wanted to become involved,” he wrote. “Its main social concern seemed limited to the issuing of used clothing to my people.”

Still, Snow never renounced his ties to the denomination. He continued to minister to the Stoneys as well as to other congregations. For him, Stoney spiritual beliefs and Christianity had emerged from the same source.

Brenda McQueen is a great-great-great-granddaughter of George McDougall, a lineage she holds dear. She is also a direct descendant of John McDougall and his first wife, Abigail Steinhauer, the daughter of the famous Ojibwe Methodist missionary Rev. Henry Bird Steinhauer. Abigail died of smallpox at the age of 22 after bearing three children.

McQueen, a former school teacher, lives in Calgary, and as president of the McDougall Stoney Mission Society, she is the driving force behind the restoration of the original mission church. “I have felt the presence of George [McDougall] for the last three years more than I ever have in my life, and I get goosebumps because I know he is proud of what I am doing,” she says, her voice rising with enthusiasm.

More on Broadview:

- Churches return land to Indigenous groups as part of #LandBack movement

- Electricity comes with a devastating cost for Indigenous communities

- Sacred Indigenous rock art sites under threat

We are sitting on the small sunlit patio at the home of Very Rev. Bill Phipps, a former United Church moderator who in 1998 issued the denomination’s apology for its role in Canada’s residential schools. Completing the circle is Tony Snow, Indigenous lead for the United Church’s regional council in central and southern Alberta and son of Chief John Snow, the minister who was so critical of John McDougall in his book.

Tony Snow wholeheartedly supports the restoration of the church. For him, it’s more than simply a construction project: he sees it as a rebuilding of the deep relationship between the Stoney Nakoda and the missionaries who introduced Christianity to them. “It’s been a tenuous relationship, for sure,” he says. “But we talk about it as being bound by the words of Henry Bird Steinhauer, who came as an Ojibwe minister into the area and who brought a different kind of Christianity into this land. It was more along the lines of what Christ was preaching: be kind to one another, be good to one another, learn from one another and do good works.”

For McQueen and Tony Snow, the church restoration is a tribute to two of their ancestors who were both involved in Treaty 7. Jacob Goodstoney, Snow’s great-great-grandfather, signed the agreement, while John McDougall, McQueen’s great-great-grandfather, was an official witness. “We wanted to [encourage] the next seven generations to work together,” says McQueen, “because we both had ancestors who were working together at that time, and here we are today working together again.” Both she and Snow see restoring the church as a manifestation of faith in the future, a sign that a fractured relationship can be healed.

In summer 2019, members of the Stoney Nakoda Nation and the McDougall Stoney Mission Society held a tipi raising at the site. And McQueen has been working with some Stoney Elders on an interpretive walk that will present the history of the mission from the Stoney point of view. “I have listened to Elders who have been in tears because they have never had the opportunity to voice [their perspective] in their language, and have a video sharing their story,” she says. “And that is what we want for them. I think this will be a good healing for all of us, to move forward.”

Phipps also sees the restoration, and especially the Stoney interpretive site, as a step toward more harmony, even though there will be bumps along the way. “As [Sen.] Murray Sinclair, head of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, said, it took seven generations or more to get to this point, so it’s going to take seven generations to repair the damage.”

It’s clear from the title of Sinclair’s investigation into Canada’s residential schools that truth must be acknowledged before reconciliation can occur. And for the Stoney Nakoda Nation’s chiefs and councillors, it is the truth of their community’s experiences with the Methodists, the United Church and the McDougall society that has driven their strong opposition to restoring the church.

In a letter dated Aug. 25, 2020, to the provincial minister responsible for historic sites, the chiefs write: “At a time when monuments to subjugation all over the world are being destroyed or removed, the McDougall Stoney Mission Society, without consulting with the Stoney Nakoda Nation’s leadership, and in the face of overwhelming opposition, has chosen to rebuild a monument (the McDougall Memorial Church), which to many of our community stands as a traumatic and painful reminder of a colonial legacy of cultural genocide and oppression.”

None of the chiefs would consent to an interview with Broadview on the matter. But publicly available legal documents and letters make their position clear. They petitioned the provincial government to rescind the historic site designation so the Stoney Nakoda Nation can exercise a previously negotiated option to buy the land for $10. They opposed the permit for developing the new church. They appealed to the municipality to revoke the permit but were denied. They appealed to the courts to overturn that decision but lost. They then issued a second formal appeal to the provincial government regarding the historic site designation.

But even as they fought it, construction of the new church continued. The $500,000 project is being financed by provincial grants, the Calgary Foundation and donations from McDougall society members and the public.

The land occupied by the Methodist mission has long been a point of contention for the Stoneys. After Treaty 7, a government surveyor included the Methodist mission site inside the Stoney reserve. When the Methodist Missionary Society protested, a second survey was conducted that placed the mission site outside the reserve boundaries. Not long after, the Missionary Society was granted an additional 61 hectares because John McDougall said he had been promised this land by government authorities. There is no paper trail for this undertaking, and there are questions about whether the Stoneys fully consented to these land transactions.

When the Methodists and other congregations formed the United Church in 1925, the new denomination gained title to the 130 hectares granted to the Missionary Society. In the 1970s, Chief John Snow undertook negotiations to get the land back. The United Church agreed to return the land except for the 17.8-hectare site of the McDougall Memorial United Church and the original Morleyville mission, the latter of which very little but some eroded foundations remained.

By this time, the McDougall Stoney Mission Society, established under the auspices of the United Church, had been incorporated. It opposed the larger transfer of land by the United Church to the Stoneys, but the transfer went ahead anyway. The United Church retained title to the 17.8 hectares, and the society became the guardian and caretaker of the church and the original mission site.

In the 1990s, after a claim was settled between the Stoney Nakoda and the United Church over mineral rights, the United Church offered to return to the Stoneys the remaining 17.8 hectares of land. The McDougall society sued the United Church, claiming it didn’t have possession rights.

Eventually an agreement was reached in which the Stoney Nakoda chiefs stipulated that once the church was no longer functioning or viable and the official historic site designation had been rescinded, the Stoneys had the option to buy the land for $10. It is this option they now seek to exercise.

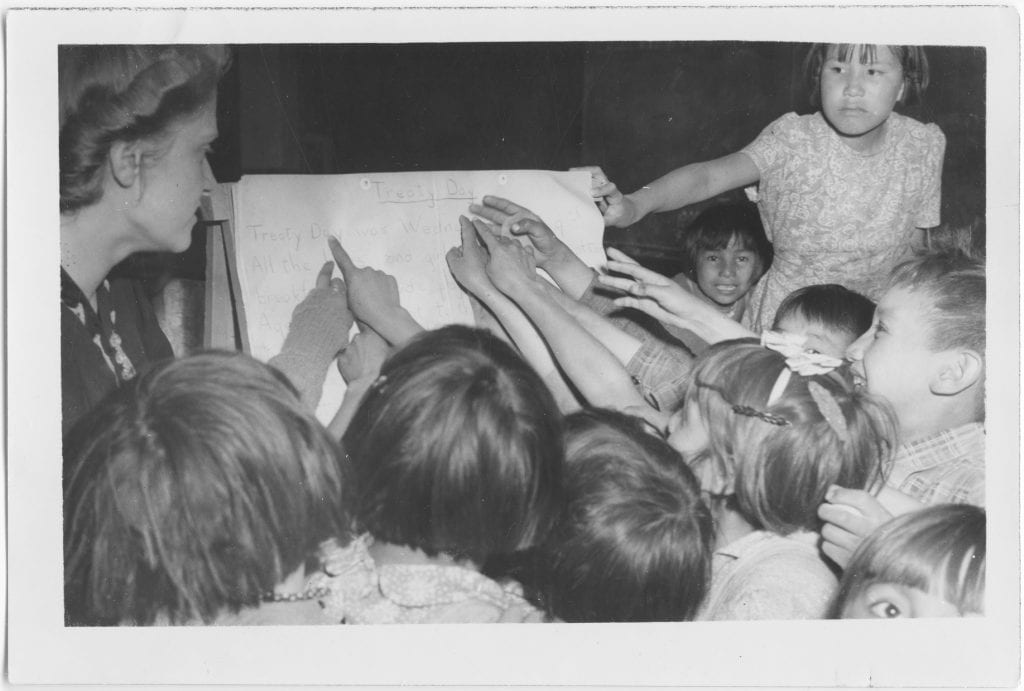

Another point of contention for the Stoney Nakoda is the residential school that opened on the reserve in 1926, a few kilometres west of the original mission site (the McDougall church was abandoned in 1921). Funded by the federal government and managed by the United Church, the school housed and educated dozens of children a year until 1969, when the residence was closed. (It continued as a day school until 1986.)

Tina Fox was sent there in 1948 when she was seven years old and didn’t speak a word of English. Except for occasional breaks and summer holidays, she would spend most of her life there for the next 11 years.

Fox says she received instruction that was as good as in off-reserve schools. But the pressure to give up Stoney spiritual beliefs and practices was relentless. “We were told that our ceremonies and our dances were the work of the devil, and if we practised those we would go to hell and we would burn in a lake of fire forever,” she says. “We would go home for summer holidays, and we would go to sun dances and stuff like that when we were home, but at the same time we were wondering, ‘Am I going to go to hell for this?’”

Today, Fox is a highly respected Elder, a school counsellor and the first woman to be elected to the Wesley band’s governing council, a position she held for 14 years. She doesn’t mince her words about the McDougall restoration project: “All over Canada, the U.S.A. and Europe, too, they are dismantling statues of people that represented slavery [and the] oppression of people. And up goes this church, the rebuilding of the church. I look at it and I think white privilege in action. My people’s bad memories, the history of the church-run residential schools doesn’t matter. I don’t think it matters to them.”

Tom Snow, Chief John Snow’s brother, boarded at the residential school for a year. As he got older, he became an alcoholic but eventually realized he had to change. In recovery, he started researching his family history and the history of the Stoney Nakoda.

“I came to understand that so much had been imposed on us…and I realized that what happened to me, happened to us as a people,” says Snow, who renounced Christianity in favour of Indigenous spirituality and is now the Elder in residence at the Bent Arrow Traditional Healing Society in Edmonton. He has been following the dispute over the church restoration and says the chiefs’ opposition gives him hope. “I stand with them.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission defines reconciliation as “an ongoing process of establishing and maintaining respectful relationships.” This can also mean “making apologies, providing individual and collective reparations, and following through with concrete actions that demonstrate real societal change.”

Brenda McQueen says the McDougall Stoney Mission Society sees the restoration of the church as an act of reconciliation with the Stoney Nakoda people. Tony Snow sees it as a way to maintain a long history and for the church to forge a better relationship with the Stoney Nakoda.

He’s sympathetic to those who object to the new church because it reminds them of their residential school experiences. “There are certain things that we haven’t dealt with that we need to work toward,” he says. Righting that wrong “includes opening up the space where the orphanage and the residential school were, commemorating that in some way and finding a way to repair.”

The Stoney Nakoda chiefs have criticized the McDougall Stoney Mission Society, saying it has failed to support the United Church apology to residential school survivors or make one of its own to the First Nation. McQueen says she’s confident that the society’s current board members would be “unanimous in support” of the 1998 apology. However, she maintains that the McDougall church has never been a functioning church under The United Church of Canada and that the McDougalls had no responsibility for, and would have been against, the residential school that was established in 1926 after the family had long departed the area.

Beyond apologies, there’s also the question of land. The Stoney Nakoda have made many efforts over the past 120 years or so to take back the original site of the Methodist mission. It is not a huge swath of land, but it is a symbolic one. “Young people are commenting [on Facebook] that [the church] shouldn’t go up, it shouldn’t be there in the first place, that land should be given back to our people,” says Tina Fox. “That’s true reconciliation.”

As the restored church neared completion, the province had yet to give a decision on the Stoney Nakoda request to rescind the heritage site designation. By early November, the exterior included a new roof, a new bell tower and walls containing logs saved from the original church and then covered with new white-painted wood siding. The interior will be finished over the winter and spring, and the McDougall society plans to hold an official opening soon after.

The new church will not be offering regular services or building a congregation. Municipal land-use bylaws don’t allow for a functioning church in that region. But the weddings and twice-yearly commemoration services will continue.

As for reconciliation, that still seems a long way off.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s January/February 2021 issue with the title “Monument to a mission.”

Gillian Steward is a Calgary journalist.

___________________________________________________________________________

We hope you found this Broadview article engaging.

Our team is working hard to bring you more independent, award-winning journalism. But Broadview is a nonprofit and these are tough times for magazines. Please consider supporting our work. There are a number of ways to do so:

- Subscribe to our magazine and you’ll receive intelligent, timely stories and perspectives delivered to your home 10 times a year.

- Donate to our Friends Fund.

- Give the gift of Broadview to someone special in your life and make a difference!

Thank you for being such wonderful readers.

Jocelyn Bell

Editor/Publisher

Comments

Rev, Stan Stainton says:

Nothing really changes. Agreements continue to be broken. Those damn Indians persist in being recognized & respected: I cry for the church as it violates its own basic tenets after apologies that apparently are meaningless.