Content Warning: Contains spoilers for Ryan Coogler’s 2025 film Sinners

The freest I’ve ever felt was when I realized I didn’t need to be a Christian.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

2024 was a pivotal year. I spent most of it attempting to understand myself, examining my beliefs and letting go of what no longer served me. I realized that my core identity, values and morals aren’t rooted in a religion but are shaped through my choices and experiences. So, I left the evangelical church.

I was only seven years old when I bowed my head at the altar of our small church and dedicated my life to God. I understood this dedication to mean attending Sunday school, reading my Bible, helping to decorate the church for Easter and singing in the choir.

As I grew older, the devotion that was expected of me began to feel unrelenting. My life no longer belonged to me. I was meant to be a vessel through which God’s will and purpose are fulfilled. My world kept expanding, and I couldn’t identify with the binary view of life as good or evil, God or Satan.

Sitting in the theatre where Ryan Coogler’s genre-bending film, Sinners, played brought back the debilitating feelings I experienced during my religious deconstruction journey. But it also affirmed my decision to untie my identity from a belief system that left me no room to breathe.

Set in 1932 in the Mississippi Delta, Sinners takes place over 24 hours and follows twin brothers Smoke and Stack (both roles played by Michael B. Jordan) who return to their hometown to open a juke joint.

Their cousin Sammie (Miles Caton) is a naturally gifted blues guitarist and singer. His father ( Saul Williams), a preacher, warns him that his musical gifts will lead to his downfall: “If you keep dancing with the devil, one day he’s gonna follow you home.”

Yet, Sammie captivated me because he insisted on pursuing his musical gift, even when that meant going against his father and rejecting the religion that became a source of hope, survival and freedom for his people.

More on Broadview:

- Being Black in Trump’s America

- ‘No Other Land’ is a cry for justice in West Bank

- The rise of the non-religious in Canada

Black churches have been at the forefront of the civil rights movement in the U.S. and helped Black people combat a system designed to keep them compliant. But Coogler doesn’t shy away from pointing out that Christianity has been exploited to create that very system of colonialism and slavery.

Through Sammie’s fight for freedom of choice and self-determination, Coogler critiques the adherence to a religion that devalues ancestral traditions and customs.

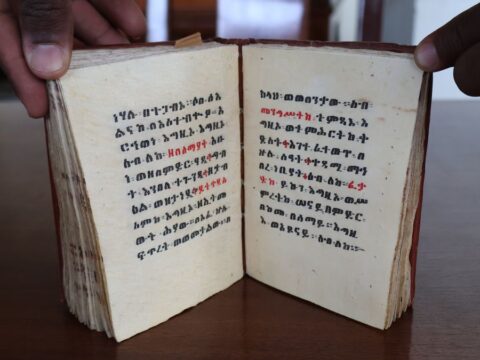

The blues emerged in the Jim Crow Deep South, with roots in West African musical traditions. While it centres the experiences of freed enslaved people and deeply influenced gospel music, some Southern Black Christians condemned the blues from its early days as “the devil’s music.”

But against his father’s wishes, Sammie lets his instincts guide him. When he gets in the car to follow his twin cousins to a night of singing, dance and drinks, he reclaims his agency and dares to live authentically.

Sinners’ portrayal of the church brings to mind the work of James Baldwin in his autobiographical novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain. He offers a similar analysis of religion and identity, where the church serves as both a source of comfort and a tool of oppression. Through the character of John, the stepson of a preacher, we see how the church’s teachings on sin, punishment and salvation harm young people, portraying them as inherently bad.

John lives in constant fear because the church teaches that sin is always in the flesh, rendering it inevitable unless you commit to a holy life. Like Sammie and myself, John struggles to reconcile his desires and uncertainties with the expectations of the church.

Baldwin makes another compelling argument that echoes throughout Sinners: The church’s preoccupation with sin and judgment doesn’t leave room for love and compassion.

When Sammie returns to the church after a night of wrestling supernatural forces, bloodied, traumatized and still clutching his broken guitar, he searches for grace and comfort. Yet, he is met with condemnation.

His father immediately offers him a chance at redemption, asking him to drop the instrument and turn to God.

But Sammie remains steadfast in his convictions — he tightens his grip around the wrecked, unplayable guitar and ultimately chooses a path that feels true to him.

Life after deconstruction looks different for everyone. Some reject their faith entirely, and others redefine their beliefs. For me, it has been an ongoing process of re-evaluation and reaffirmation.

The energy I previously directed towards following a divine plan is now spent living much like Sammie does in the post-credit scenes: with an eye towards living fully, creating art and immersing myself in the human experience without guilt or shame.

***

Dominique Gené is a French and English journalist and writer based in Ontario. She was the 2024 recipient of the CJF-The Globe and Mail Black Business Journalism Fellowship.