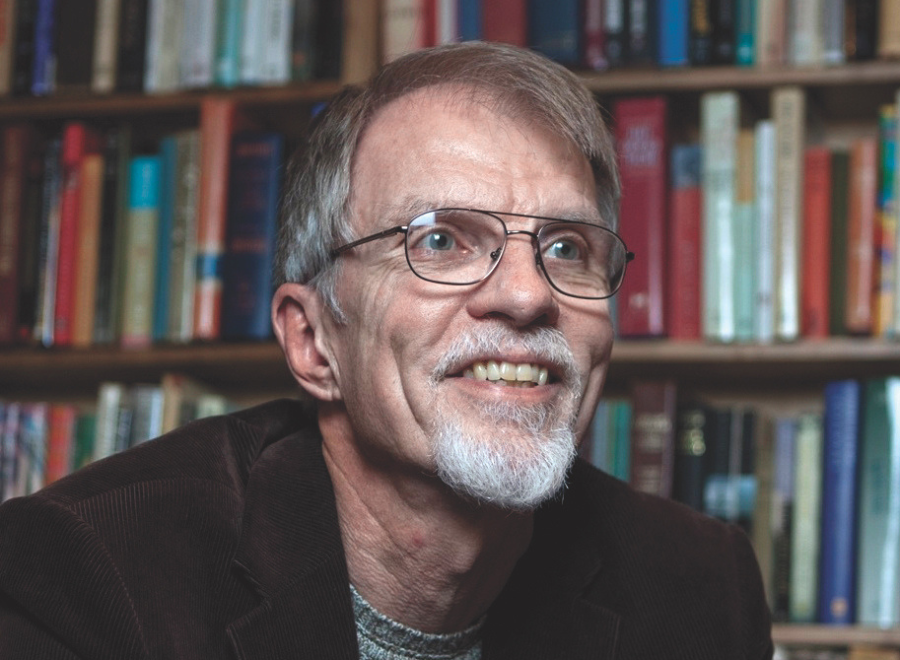

Rev. Tom Sherwood is a former campus minister who teaches at Carleton University in Ottawa. In 2009, he was awarded the United Church’s McGeachy Scholarship to conduct a research project on youth and young adults called Listening to the Echo. He spoke to Richard Wright.

Question: Describe your project. What exactly does Listening to the Echo mean?

Answer: Well, “echo” refers to the echo generation, the children of the baby boomer generation, born after 1978. They’re mostly in their late teens up to about 30. And they are different from my own and earlier generations. When Martin Luther King was that age, and Stanley Knowles and Lois Wilson and Bill Blaikie and I were that age, working through the church was a viable choice as an arena for making a difference in the world. It made sense. But for the echo generation, it isn’t making as much sense. As a front-line campus minister for more than a decade, I’ve had an unusual opportunity to listen to a lot of people of that generation who, at that critical discernment stage of life, have not seen organized religion as a viable choice for them. So the church has asked me to bring their voices into church life so we can all listen.

Q: It’s not breaking news that young adults these days aren’t enthusiastic about the church. What are you bringing to this matter that is fresh?

A: What I hope I’m bringing is people telling me why they aren’t choosing to function through the church, and what they are doing instead.

Q: What is your method? How are you doing this?

A: I’m starting with the people I know. I’ve had hundreds of young adults contact me, and it’s a matter of getting their permission to make them part of this study. A lot of this has been done by e-mail, which is great, because I get to quote them exactly, but I’m also sitting down with people.

Looking over the first 50 [interviews] or so, I realized that this process has a number of biases in it, so I will need to extend it, to make it a little more national, for example. I met with the network of campus ministers in Saskatchewan in June, and they said they would help me connect with young adults there. It looks like I’ll be meeting with a group of students in Montreal and in Halifax.

I’m making an effort to increase the interfaith spectrum, too. Without working at it, I have Sikh, Jewish, Aboriginal, Muslim, Hindu and Buddhist young adults in the population, but only two or three of each.

Q: How many people have you spoken to so far?

A: One hundred and eighty. I’m hoping to speak to at least 300 young adults altogether. I’m supposed to report in 2012.

Q: Can you give us a preview? What have you been hearing?

A: The echo generation is a treasure. I’ve been privileged to hear the beauty of the spirituality of young people who are not in church life. They’re choosing, in growing numbers, to be spiritual, albeit in ways that don’t involve congregational committees, Presbytery or Sunday morning hymnbooks. And while this may not be the best choice from the point of view of the institutional church, I still think it’s tremendous.

So I am hearing them voice their spirituality and their growing commitment to ethical citizenship as well. They have a very positive attitude toward social engagement. When I bring their voices to the attention of the church through this project, for example, I know already that I can represent their energy for responding to the environ- mental crisis. I’ve had the privilege of hearing that voice in many, many individuals in my sample, and it has inspired me and given me hope.

On the downside, I’m hearing a lot of ignorance about the United Church, confusing us with Catholicism and American fundamentalists. without distinctions. To me, as a United Church leader, that’s so disappointing.

The official theology of the United Church is something that many of these young adults would embrace if they knew about it. They often articulate it. That we’re not alone. That we live in a world with a sacred being. That there is hope and so on. And they don’t know that they are practically quoting United Church spirituality.

Q: How does the church stand to benefit from this project?

A: My first answer is I don’t know for sure. There may be a practical result, learnings for curriculum writers, program designers and leaders in local congregations.

I think that if we listen with an open mind to what this generation is saying, we may feel a little less gloomy as one news story after another, and as one church experience after another, says decline, decline, decline. I think these voices are bringing hope, and by introducing them to the church, I may be alerting us to a spiritual transformation we could celebrate — even though it may be taking place outside the institutional church.

It could also be — and this is exciting for me to imagine — that there will be a relationship in the future between the Christian tradition as we’ve known it and this echo generation’s spirituality. If we listen. And if we are open to new ways.

Q: Is the church, in fact, listening to the voices you have recorded so far?

A: When I made an overture to the United Church campus ministers, they were very encouraging. My presentation at More Franchises: A Second Cup [a United Church conference] in Toronto last June was well attended. Berwick Camp [a United Church camp in Nova Scotia] also invited me to speak.

So, yes. Even at this early stage.

Q: How does that observation square with cutbacks announced late last year, particularly the elimination of the youth and young adult staff position in the General Council Office?

A: Personally, I was upset by the cuts. I couldn’t understand cutting the staff person, Rick Garland, the year before Rendez-vous 2011 [a national event for United Church youth and young adults]. We knew that difficult cuts had to be made, but the communication of them was terrible. To all front- line folk engaged in campus and YAYA [youth and young adult] ministry, it sounded like the church was de-emphasizing their work. And frankly, it seemed like a repudiation of what the McGeachy award to me for my project had said was important: Let’s look to the future and be willing to change. Let’s respect campus ministers as leading-edge and as glimpses of the future and as resources, and let’s make sure they’re supported and encouraged. I was disappointed, and I communicated that to church leaders personally.

Q: You’re a church leader yourself. How has what you’ve been hearing changed your thinking or your practice?

A: I’m not sure that it has changed my thinking, so much as confirmed my belief in something I’ve been thinking for a while, and that is that we need to come to new terms with our present reality.

Life is change, and if we’re going to celebrate God, the creator of life, we need to find ways to celebrate change. We need to find ways to celebrate the fact that the future is going to be different from the past.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s January 2011 issue with the title “This United Church Interview: Many young people would embrace United Church theology if they knew about it.”