Canada deported my dad to the wrong country. His name is Ismet Hajrizi. On a Wednesday in June 2019, he went to his regular appointment with the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), something that refugee claimants are often required to do as a condition for staying in the country. These check-ins with immigration officials were a convention of my father’s life within the asylum system. Rarely did they give him much trouble.

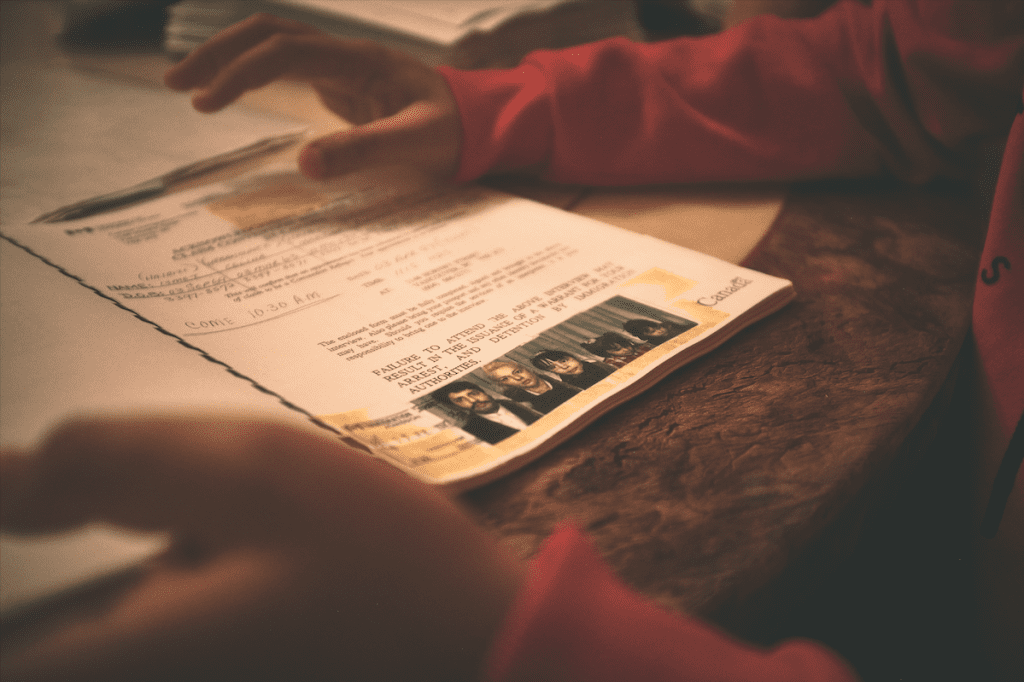

This time, when he showed up at the office in Ottawa, they served him with a deportation order, giving him 11 days before he was to be sent to Kosovo, a country to which he has no legal connection; a country that wasn’t even a country when he left Europe; a country where Roma people like us face discrimination, prejudice and genuine danger.

My sister tried to reach me to let me know what was going on, but she was unable to get through. It was her boyfriend who eventually got a hold of me, which was odd — he never called. “Get dressed and go to CBSA headquarters,” he instructed. “Your mom will meet you there.”

Knowing nothing, I drove to the headquarters in downtown Ottawa, a tall, bland concrete and glass building. Maybe we had been granted status, I allowed myself to think. I’d always told myself my time would come, and maybe this was it. But right away, I could see my mom, Celina Urbanowicz (Mama Celina, we call her) pacing — it’s what she does when something’s wrong. “They want to deport Dad,” she said. I asked her what she was talking about, but nobody knew much more than that. Nothing made much sense.

Family separation has entered the public lexicon, but it’s often thought of as something that happens at the southern U.S. border or on migrant ships in the Mediterranean or somewhere else far away. And yes, that’s one form of family separation. But we live with another kind. We’re not separated in transit; instead, we are separated by the state. We live the kind of life that most people don’t think about — a life without status. And when you live without status, the Canadian immigration system is a constant presence. We’ve been pulled by it, stressed by it, scared of it, even protected by it. And finally, we were split apart by it.

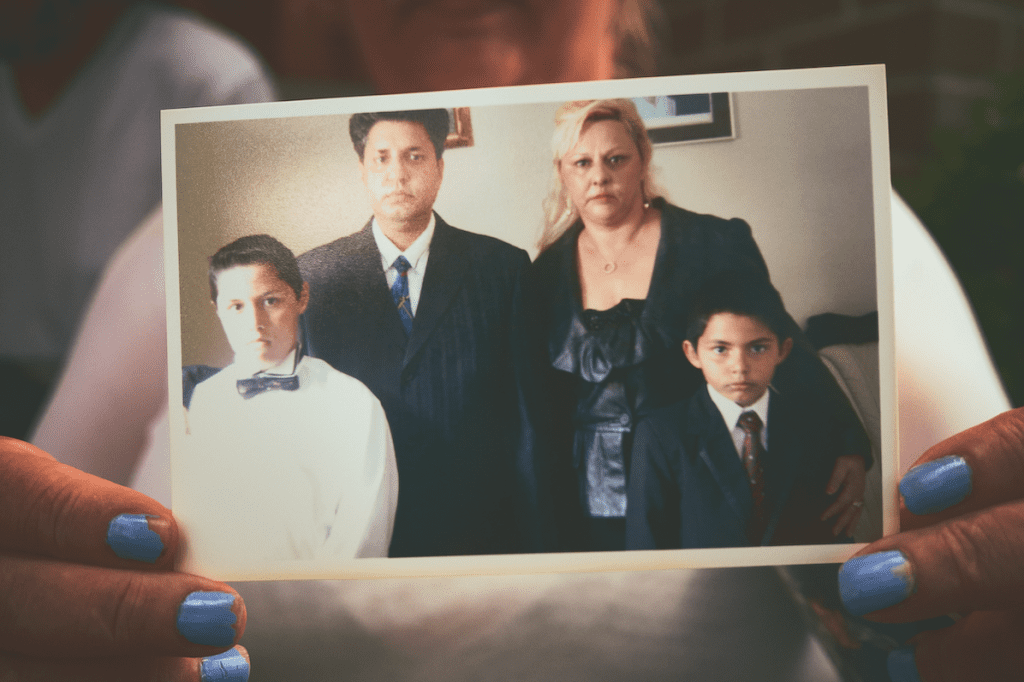

International boundaries run right through the middle of our family like train tracks. We were together as a family, building a life here and surviving, all in spite of those boundaries. My mom was born in Poland, where she was forced into an abusive arranged marriage that she eventually fled. Marrying my father, a Roma Muslim born in what was then Yugoslavia, destroyed her relationship with her family.

The former Yugoslavia was never a safe place for our Roma family. Ethnic Albanians, angry and reeling from a bitter war with the Serbs, often targeted Roma people in the 1990s, making us the scapegoats. Like many Roma people in central and eastern Europe at the time, we fled to Canada in 1997. My parents were still young and beautiful, and their decision to leave seems obvious and unimaginably hard at the same time. I was only three years old; my younger sister was two. Officially, we’re both considered stateless; our births weren’t, and aren’t, recorded anywhere in the world. My two younger brothers, both born here in Canada, are full citizens. As kids, we all called Canada our home and our country, and we called ourselves Canadians, which technically was only partly true. But it was the whole truth to us.

I don’t remember when I learned that we didn’t have status. My parents didn’t talk much about it. Instead, they kept all of this to themselves, so that we’d grow up as normally as we could. They tried to keep away all the stress and the worry, but you can’t hold it at bay forever.

It’s as you grow up that the lack of status slowly begins to exclude you from life. It hits you in surprising ways. When a friend was getting married, I began to wonder if that would ever happen for me. How could I make it official without a passport? As everyone else’s life develops and blossoms, I have felt like I’m on the sidelines, watching people live their lives. You can handle it for a while, but at 26, I’m tired of watching from the bleachers.

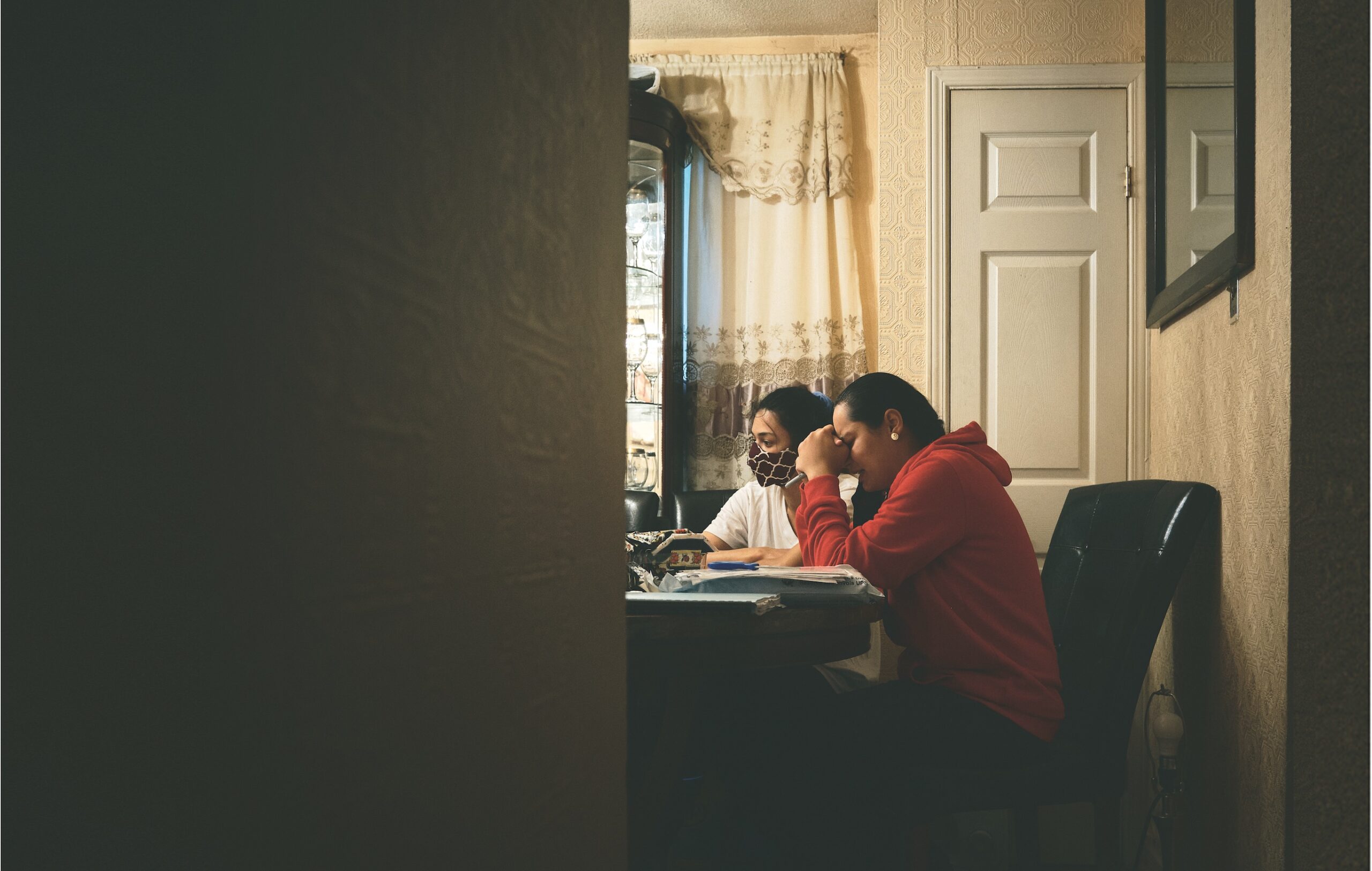

As I processed the news at the CBSA headquarters, the weight of my father’s deportation began manifesting into a headache and a spacey feeling of shock. I knew only one immigration lawyer, who I’d worked with a few years prior, so I called him. He went up to Montreal to try to get my father out on a detention review. It didn’t work. We tried to go to federal court to stop it. That didn’t work, either.

A mechanical issue with the plane intended to take my father out of the country pushed his deportation date back by about two weeks. Seizing the gift of time, we got a new lawyer and a new application to federal court. None of it worked. So late at night on June 30 — as people across the country got ready to celebrate Canada Day, our multiculturalism and our history — my dad was packed onto a plane and shipped away.

My mother still feels that she never got a chance to say a proper goodbye. The final visit we were promised — no orange jumpsuit, no handcuffs, just us and Dad — never happened. We said goodbye to him over the phone instead.

The things I miss the most about him are all the little things that made up his presence: his bad singing, his big smile, his unsuccessful attempts to teach me to love soccer. How he loved to look his best. I remember that our fridge was always full of ice cream. There were a lot of kids in our neighbourhood growing up, and our dad was the kind of guy to hand out ice cream when he saw them playing in the streets. I remember the man who was soft and caring, like a teddy bear.

After he was taken away, I felt unsettled — I had so many questions. Why wasn’t there a warning? Why didn’t we get a letter? Why was he taken now? Nothing made sense.

In search of answers, I went down to the basement, where we stored boxes and boxes of immigration documents. At first, I didn’t know what I was looking for, but slowly I started piecing everything together. I basically conducted my own investigation. When lawyers would represent us, they wouldn’t really look into that sort of stuff; they would just deal with whatever was lying ahead of us. They never knew our history. I didn’t know it, either.

My parents first tried to get refugee status when we arrived in 1997, but it wasn’t easy for Roma people at the time. In the early 2000s, the position of the Canadian government was, essentially, that the treatment of Roma people in Europe didn’t amount to systemic racism or persecution, and that European authorities would protect us if we were discriminated against. But that bore little resemblance to the world we and other Roma people had left.

In May 2000, a judge denied my parents’ initial refugee claims, and their application for a judicial review was dismissed after a lawyer failed to submit the right paperwork on time. My mom and dad didn’t speak English and didn’t know that their case had been dismissed. My mother had requested a Polish-speaking translator for that application; the government gave her one who spoke Croatian instead. They knew the ruling didn’t go in their favour, but they never understood why or what that meant for them. Since then, we have lived in Canada as failed refugees — not officially part of Canada, but attached to it all the same.

Our family, and other Roma, have put our faith in lawyers and in the system itself, only for both to fail us.

In 2008, the country attempted to deport our entire family save for my two Canadian brothers, who would have been placed in foster care. At the time, CBSA officials thought we were Albanian and didn’t believe us when we told them otherwise. United Nations officials in Kosovo did an investigation and informed the CBSA that we were Roma, not Albanian, and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees said that warranted international protection for our family. It was enough to halt the deportation, but not enough to grant us status, and so we went back to an undocumented life.

We were left alone for 11 years, living life as normally as possible. I brainwashed myself into an unrelenting optimism, convinced it would all eventually go my way. I told myself that my time would come.

As Roma people, it is as though we have been blessed with a curse, marked by someone or something. We are a forgotten minority. Across Europe, we have experienced violence and hate speech, discrimination and social exclusion, but it’s almost never talked about in public. We’ve tried for so long to fight for basic human rights. Many of us just stopped speaking out entirely, having learned that we won’t get the help we need.

Since we’ve arrived in Canada, our claim to refugee status has been simple: send us back to Europe and you would be sending us back to a place where Roma people face persecution and oppression. The Roma people have long been, and still are, historically stateless — we have never had a national homeland. The Canadian government’s idea of where we ought to be returned to now includes a mosaic of post–Yugoslavian states, many of which have a very recent history of oppression against Roma people. Here, you can call the police to report hate speech and the police will come; when it’s in Europe and you’re Roma, odds are they won’t even show up.

Canada’s immigration system was never all that welcoming to our people, and it frequently rejected our asylum claims. Waves of Roma migration over the past few decades might have opened the country’s eyes, but often Roma people are greeted as if we’re here to game the system. In 2009, an article in the Toronto Star described Roma children as “lukewarm to learning, even suspicious” and complained about our “limited education and an often shaky regard for school.” In 2012, then-immigration minister Jason Kenney falsely stated that most refugee claims from the European Union were bogus.

More on Broadview:

- A Sixties Scoop survivor’s healing journey

- Muslim detainees forced to pick between pork and rotten halal food: lawyers

- Migrant workers in Canada deserve a better deal

That many of us are fleeing countries considered safe by the Canadian government has been used to cast doubt on the legitimacy of our claims. As recently as 2017, lawyers and immigration advocates reported Roma people being refused on flights to Canada from visa-exempt countries — denying them the opportunity to make legitimate asylum claims.

Those of us who manage to get here continue to face unfair barriers. I say three words a lot: repeated lawyer negligence. For most people, this might seem like an excuse for a decision that doesn’t go our way. A lawyer screws up once or twice? It happens. People are busy. But after a while, it seemed that every time we tried to get status through the proper channels, lawyers — whether they meant to or not — dropped the ball.

“There has been a huge problem with a handful of unscrupulous lawyers and consultants who have actually done an injustice to this community,” Maureen Silcoff, a lawyer and representative of the Roma Community Centre, said in 2012. She was speaking to the House of Commons’ standing committee on citizenship and immigration, a month before Kenney’s Bill C-31 would make it harder for Roma refugees from a list of supposedly safe countries to claim asylum. (All countries were removed from the list in 2019 after federal court intervention.) “People lose hope,” Silcoff said. “The lawyers don’t show up. They don’t answer their phones.”

Our family, and other Roma, have put our faith in lawyers and in the system itself, only for both to fail us. In 2006, my family tried to apply for status on humanitarian and compassionate grounds (what we call an H&C) — an immigration program that, essentially, makes exceptions for special cases. We waited and waited. We were still waiting in 2013, when we were finally told that the application was denied, without any given reason. By the time we had gathered legal opinions, the 15-day deadline to apply for a judicial review had already passed, and the lawyer told us that since we’d received a negative decision we’d have to wait a couple of years until we could apply again.

Waiting and patience are luxuries we can’t always enjoy; it is as if there’s a ticking clock counting down our time in Canada, one that is invisible to us, often until the moment we’re told it’s run out. We can do all manner of things to try to slow it down, stop it or even add more time, but — as was the case for my father — once it’s up, it’s up.

Shortly after my dad was deported, my mom was told by the CBSA she could submit a pre-removal risk assessment, something that only happens once the agency has started the removal process against you. It is your chance to state your case, once again, that you are in danger of persecution in the place you would be sent. A couple of months later, my sister and I were both given notice as well; we were in the CBSA’s sights. Waiting for a pre-removal risk assessment to be considered can buy you time — sometimes six months, sometimes a year and a half. But it doesn’t stop the clock forever.

Just after the new year, my sister and I got a break — our application for humanitarian and compassionate grounds was finally accepted in the first stage, a kind of pre-approval that means we are moving through the proper channels toward permanent residency. It is a bittersweet thing. Being granted permanent residency would mean a lot for us, not just that we aren’t going to be deported, but that we will no longer have to live in constant fear. Yet it also confirms for me that our case was valid all along, and that maybe my dad never should have been deported in the first place.

How can I blame Canada for any of this? All that we have — our freedom, our family, our lives — is thanks, in some way, to this country. Being here, my family and I have had a chance to live without persecution. As an LGBTQ2 woman, I have not had to hide from society. Our parents were able to raise us to be comfortable in our own skin.

All we have ever wanted is for the Canadian government to live up to its words. Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland has recognized the danger Roma people, in particular Roma women, face in the world. And the current Liberal government is the first to acknowledge the Roma genocide in the Second World War. In public, they say all the right things.

But the fact remains: my family feels ruined. My house is no longer a home — it’s just a place where I sleep and sometimes eat. The photos of my father have all been taken off the wall and packed away, too painful for my mom to be surrounded by. We are facing the very real possibility that the Canadian government will separate us again, sending my mother to Poland. My father already lives in hiding. When he arrived in Kosovo, he moved into a garage with a carpet and a few blankets. We wake up every day wondering if he’s dead. How would we even know? Who would tell us? Who is there to keep him safe?

Immigration officers are reviewing my mom’s pre-removal risk-assessment application now. Even still, she is required to report to the CBSA every month, and every month we fear she will be swallowed by that building and be sent halfway around the world. We sit and wait, fearing that the nightmare we’ve been living for the last year and a half will start all over again.

Some days, it feels like the psychological trauma will never stop. This wasn’t, and isn’t, something that just happened to my father. Deportation ripples for a long time, leaving pain and absence in its wake. The whole family feels it. We felt that once he was gone, we were next. A lot of Roma wave the white flag and abandon their refugee application. Some go back.

For those of us who stay without status, sometimes it feels like we’re invisible. I’ve been trying to fight the clock, and by now it seems like everybody in Ottawa knows my story. Local media have reported about my family. I’ve sent hundreds of emails and made countless phone calls. For a cold week in December, I camped outside the prime minister’s office. I think about going on a hunger strike. All of it because I want to be visible, to make what’s wrong right again.

There are times when things just get so overwhelming that I wait until everyone is asleep, and I cry. But the next day, I get up in the morning and tell myself, “Okay, you’ve had your 10 minutes of being weak. Now it’s time to pull up your socks and just keep going.” The more we speak up, the better chance we all have. Folks reach out to my sister and I to say they’ve had the same experience. They’re saying thank you for speaking for the silent.

The Roma flag has three colours. Blue, for the sky, symbolizes freedom. Green, for the grass, represents the land from which we live. And the red wheel is the symbol of our travels. It is for this flag and this people that we’re fighting. For our right to our own history, our own story. All we want is a fair, equal opportunity — for us, and for all the other versions of us. And we’ll keep fighting, piece by piece, until our family is back together again, here in Canada, our home. Our time will come, I tell myself. Our time will come.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s November 2020 issue with the title “Torn apart.”

Roksana Hajrizi is an activist in Ottawa. Kieran Delamont is an Ottawa-based writer.

We hope you found this Broadview article engaging.

Our team is working hard to bring you more independent, award-winning journalism. But Broadview is a nonprofit and these are tough times for magazines. Please consider supporting our work. There are a number of ways to do so:

- Subscribe to our magazine and you’ll receive intelligent, timely stories and perspectives delivered to your home 10 times a year.

- Donate to our Friends Fund.

- Give the gift of Broadview to someone special in your life and make a difference!

Thank you for being such wonderful readers.

Jocelyn Bell

Editor/Publisher

The Romap eople have been treated poorly throughout the world, maybe it is time for us to show some compassion and give these people a break and let them in!

So sad, and we hope that with the sisters’ status, father can be brought to Canada. Thanks to Roksana for sharing from the Roma difficult migratory experience.

As a first generation Canadian whose parents were refugee children from overseas, I am deeply, deeply ashamed that my country has discarded compassion in favour of rules. It is difficult for me to believe that we have people in positions of authority in our government who appear to have adopted the harsh and intolerant attitudes and characteristics of nationals from countries where freedoms are only dreamed about. My elementary school teachers taught me that Canada was a land filled with honest, decent, hard-working, compassionate citizens . . . but over the decades I have discovered that they lied to me. I am so sad for all the hopeful immigrants who look to our land as a place where they can make a positive contribution, and then find they are not wanted here. This is utterly unacceptable.

2. Despite the waves of Roma migration in recent decades, how persistent are negative perceptions and discriminatory attitudes towards Roma communities in Canada? regard Telkom University