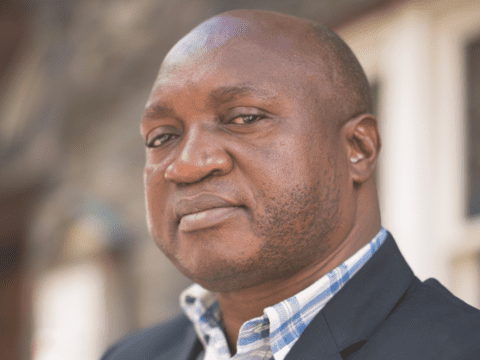

Andrew Bennett, a career civil servant and academic, was named Canada’s ambassador for religious freedom in 2013. He spoke to Mike Milne in Ottawa.

Mike Milne: Why is religious freedom important enough to be pursued as a foreign policy priority?

Andrew Bennett: Religious freedom is fundamentally about human rights; it’s not a theological issue. It’s about advancing human dignity and the right every human being has to practise their faith or to choose not to have religious faith. In Canada, we’re very fortunate in having a pluralistic, multicultural, multifaith society. We have religious freedom in Canada. And in many ways, we project a Canadian understanding of human rights and Canadian values out into the world in our foreign policy, so we wanted to do the same in regard to religious freedom.

Why are we doing that? Religious freedom is in a dire situation in the world today. The trend over the last decade has been the steadily increasing persecution of people of faith in many countries. A lot of the countries in that cohort are very populous, but the concern is the trend. The government of Canada, seeing this trend, felt that Canada needed to have religious freedom as a core component of its foreign policy and human rights framework.

MM: Have you been well received in diplomatic circles?

AB: I’ve found over the past year, through reaching out and engaging actively with my colleagues at the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development, that there’s a lot of support for what we’re doing. I’m the new kid on the block, so in many ways I’m really here to act as a resource for my colleagues, to help them have a more engaged and informed approach to dealing with religious persecution.

MM: What is your religious background?

AB: I am Ukrainian Greek Catholic. I grew up Roman Catholic but found as I went through university that I was looking for more, a deeper faith. And eventually that led me toward Eastern Christianity and the Orthodox tradition. I’m a subdeacon, so I’m clergy in the Byzantine tradition.

MM: Should Canadians with no religious beliefs care about religious freedom?

AB: Absolutely. If we don’t have religious freedom in society, it’s very hard to also have freedom of expression, freedom of association. All these different human rights are linked together. When we look at freedom of religion, it’s the freedom to openly — publicly or privately — profess your faith. It’s the freedom to engage in public worship in peace and security. It’s the freedom to engage in missionary activity. And here’s the real acid test: does a country allow people to freely convert to another faith? Conversely, does it not force them to change their faith?

There must also be an understanding that people should be able to not have religious faith. But the vast majority of people in the world who are suffering as a result of the denial of religious freedom are people of faith.

MM: Does Canada’s definition of religious freedom mean that any group should be free to proselytize in majority Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu or officially atheist countries?

AB: We’re not interested in advancing any particular faith’s proselytizing activities. In Canada, we have our own warts in our history: Catholic-Protestant conflicts, some institutional anti-Semitism just a half-century ago. But as Canadians, we’ve worked through these sorts of things, and our understanding of religious freedom is very much in line with the international concept. Faiths that choose to proselytize or engage in missionary activity in Canada have that right under religious freedom. When we are speaking to other countries, we try to encourage them that it’s all right for these groups to engage in missionary activity, and to have an understanding of religious freedom that permits that.

But many countries that are more homogeneous and have a different history from Canada might respond to those activities in a different way. They might feel a certain degree of hostility toward new groups coming into their country. Does that mean we have to soft-pedal religious freedom to accommodate their views? No. But in speaking to those governments or authorities, we need to have an understanding of where they’re coming from, so we can have a dialogue with them.

MM: Where is religious freedom most oppressed today?

AB: Certain countries have strict government restrictions on religious freedom — say China, Saudi Arabia or Iran — but very little in terms of social hostilities. Then you have a country such as Nigeria, where there are virtually no government restrictions on religious practice, yet you have a population that is divided 50-50 between Christians and Muslims, and a high degree of sectarian violence and social hostilities. Then there’s Egypt or Pakistan, where you have both social hostilities and government restrictions. Other countries we are focusing on include Indonesia, Iraq, Russia, Turkey, Syria. They are all distinct.

When we establish that we want to focus on a particular country, we are not interested in pointing fingers. What we are trying to accomplish is to have a deep dialogue and engage with that country. With certain countries, we can’t do that. Iran is a classic example. We have to issue frank, pointed statements about the egregious violations of religious freedom there. But with countries such as China, we want to have a dialogue around the role that religious faith plays in society.

MM: Aside from dialogue, what can Canada do?

AB: Advocacy, to go out and engage with foreign governments and have frank discussions about where we see particular areas of concern. This can take place overseas, and I have been to roughly 11 different countries now, some of which are like-minded. With others, such as Kazakhstan, Hungary or Turkey, we have some frank discussions about concerns we have. There are the usual diplomatic tools. We can issue démarches [warnings or protests] against particular governments when we have issues of concern. We can issue statements when there are particular events that have taken place. And we can also develop with our embassies and high commissions abroad different ways to engage governments through a common policy on religious freedom.

That leads to the third part, which is programming. We have an annual budget of $5 million for the office, of which $4.25 million is the Religious Freedom Fund. We’ve already announced projects in Nigeria, Indonesia and with the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, mainly in central Asia, to expand their understanding of religious freedom.

MM: Do you see any hopeful signs of religious freedom increasing?

AB: I’m not so naive to think that we are going to change things overnight in countries like Pakistan, China or Iran especially, but I think we can have some small victories along the way. And if Canada and other like-minded countries are not going to do this, who is?

MM: Have your actions alleviated early fears that this office was a government ploy to gain votes from Canadian ethnic and religious groups?

AB: I hope that over the past year, through the actions this office has taken and my not being a partisan player, [we have shown] that we are about good public policy and good foreign policy. There are a lot of communities in this country that are supportive of this office. They help to inform our work because they have perspectives on what is happening in certain countries. I would hope that people see the office and measure it by its words and by its actions.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s September 2014 issue with the title “‘Religious freedom is fundamentally about human rights. It’s not a theological issue.’”