EDITOR’S NOTE: This story is from our archives and first appeared in Broadview’s November 2016 issue with the title “A place to visit and remember ancestors.”

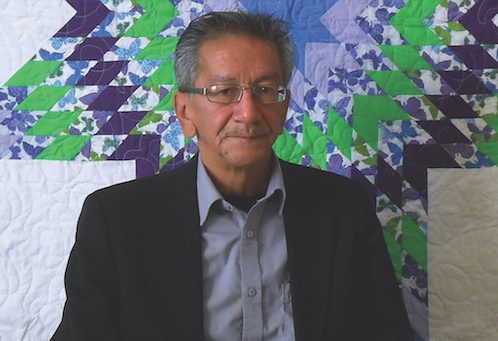

When Anthony Dreaver Johnston first learned that he might have relatives buried in the Regina Indian Industrial School (RIIS) cemetery, the 60-year-old visited the graves of his deceased parents and grandparents on the Mistawasis First Nation in Saskatchewan where he lives. He told them that he was going to visit ancestors, a four-hour drive south to Regina.

Dreaver Johnston had seen a document, produced by a group of cemetery researchers, which listed the names of children who might be interred at the site. (He now sits on the board of the RIIS Commemorative Association, the group that supplied the list.) Among them was a girl from Mistawasis with the last name Dreaver. Although her first name is unknown, Dreaver Johnston believes she was his maternal great-aunt, Catherine.

Catherine Dreaver arrived at the school in 1899 along with three of her brothers, one of whom was Dreaver Johnston’s grandfather. He recalls hearing a family story about his great-aunt.

More on Broadview:

- Once abandoned, this cemetery became a marker for Indigenous reconciliation

- The legacy of residential schools lives on in Canada’s healthcare system

- Residential school survivor wants Catholic Church to pay millions originally promised

“The brothers returned home from school one year and their parents asked, ‘Where is your sister?’ They said they did not know and thought she had returned home before them. Their father likely spoke with the community’s government official or Presbyterian minister who contacted the school. The response was simply, ‘She died a couple months ago.’”

Dreaver Johnston believes his paternal great-uncle, James Johnston, is also buried in the cemetery. James arrived at RIIS in 1893 when he was 10 years old. Not much else is known about him, except that he never returned home and died sometime before the end of 1897.

It’s unlikely that his deceased body was transported home to Mistawasis First Nation, because the reserve is more than 400 kilometres away — a long distance to travel in a horse-drawn carriage.

Although he grieves for his relatives who didn’t make it home, Dreaver Johnston is also grateful for the opportunity to honour their memory.

While at the Mistawasis cemetery, he filled a small jar with dirt and later scattered it on the RIIS cemetery. He has also gathered dirt from the RIIS cemetery and plans to scatter it on the Mistawasis cemetery.

“What I am doing,” says Dreaver Johnston, “is simply my personal ceremonies to connect my ancestors to home.”

Dreaver Johnston has also been gathering pebbles from Mistawasis and plans to build tiny stone markers at the RIIS cemetery for his great-aunt and uncle.

“I now have another place to visit and remember ancestors,” he says. “I now know their names. I know my grandparents are smiling, knowing that I visit the resting place of their sister and brother.”

***

Evie Ruddy (they/them) is a freelance journalist living on Treaty 4 lands.

We hope you found this Broadview article engaging. Our team is working hard to bring you more independent, award-winning journalism. But Broadview is a nonprofit and these are tough times for magazines. Please consider supporting our work. There are a number of ways to do so:

- Subscribe to our magazine and you’ll receive intelligent, timely stories and perspectives delivered to your home 8 times a year.

- Donate to our Friends Fund.

- Give the gift of Broadview to someone special in your life and make a difference!

Thank you for being such wonderful readers. Jocelyn Bell Editor/Publisher