On March 14, 2020 — the day after many of us went into a quarantine that would swallow up the rest of that year and now much of the year that has followed it — Rosanne Cash (the daughter of musician Johnny Cash and an artist and author in her own right) tweeted, “Just a reminder that when Shakespeare was quarantined because of the plague, he wrote King Lear.”

The tweet was met with hostility (as is Twitter’s usual way), but of course meant cheerfully — a goad to quiet productivity, a comfort as old crafts came out of closets. Cash’s claim is also more or less plausible: the bubonic plague swept through Shakespeare’s London in waves, necessitating extended closures of the theatres and affording him long periods to pen his sonnets, poems and plays.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

More on Broadview:

- Meet the director removing anti-Semitism from Oberammergau’s famous Passion play

- White Jesus is grounded in colonialism. Black Jesus is rooted in liberation.

- Grieving at my own pace

What the tweet does not register is the desperation or the loss of those years.

The plague brought Shakespeare productivity, but at an uncountable cost. One of his twin children, Hamnet, died in the plague period of 1594. Lost children proliferate in Shakespeare’s plays thereafter.

The world changed, and the writer with it. I finished my dissertation on 17th-century English literature some time before the coronavirus became part of our lives. But now that I’ve endured the months of isolation and despair that followed Cash’s well-meant tweet, what it means to create in the shadow of such great minds and such great suffering feels to me altogether changed.

Cash’s gesture to Shakespeare’s towering greatness is almost as old as Shakespeare himself. In 1630, at only 22, the young aspiring poet John Milton (upon whom my podcast, The Devil’s Party, focuses) published his first poem, writing with envy about the living tomb Shakespeare had made in the hearts of his admirers, “sepúlchred in such pomp” to rival kings.

This coveting of poetic fame haunted the young Milton for years; he wrote to his wealthy father repeatedly, borrowing toward the grand project that never seemed to materialize.

Instead, Milton became absorbed in the politics of his age, burning out his health and eyesight in the service of Oliver Cromwell’s rebellion against the king in the English Civil War and subsequent republican commonwealth. Advocating for a freer press, the right of divorce and above all the execution of tyrants, he became polemicist-in-chief for a failed cause.

By 1660, the monarchy was restored with Charles II on the throne — a king whose father’s death Milton had directly advocated. Milton’s political books were burned by order of the crown, and his royalist opponents delighted in the fall of the “blind adder” whose venom had led England “into the ditch.”

Old, blind, disgraced and broke, Milton fled into hiding with his family, his dreams of glory dashed, and the great poetic work he had promised all his life never even begun. It was now all too late.

Then, in 1665, the plague came.

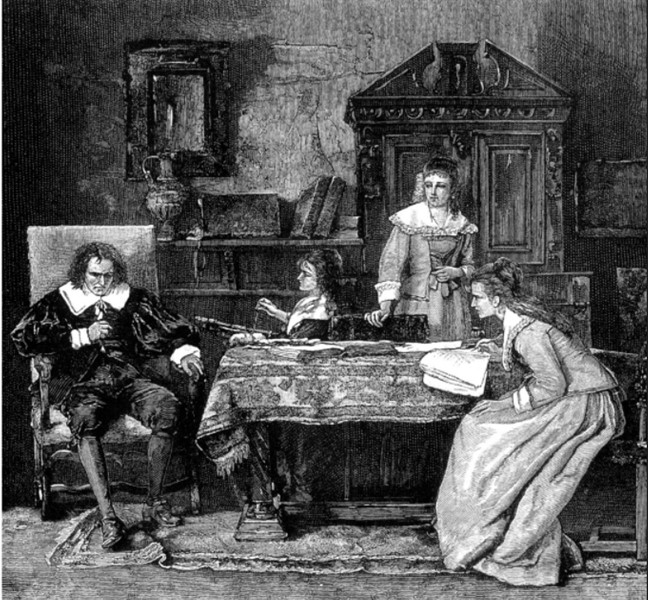

Records indicate that friends and foes alike thought Milton was dead by that point — perhaps felled by disease or scooped up in a bloodthirsty political purge. Instead, with the help of bright young friend Thomas Ellwood and his fellow Quakers (themselves persecuted for their religious nonconformity), the elderly Milton was evacuated to quarantine in a small cottage on the rural outskirts of London. There, something wonderful happened: Milton began to compose.

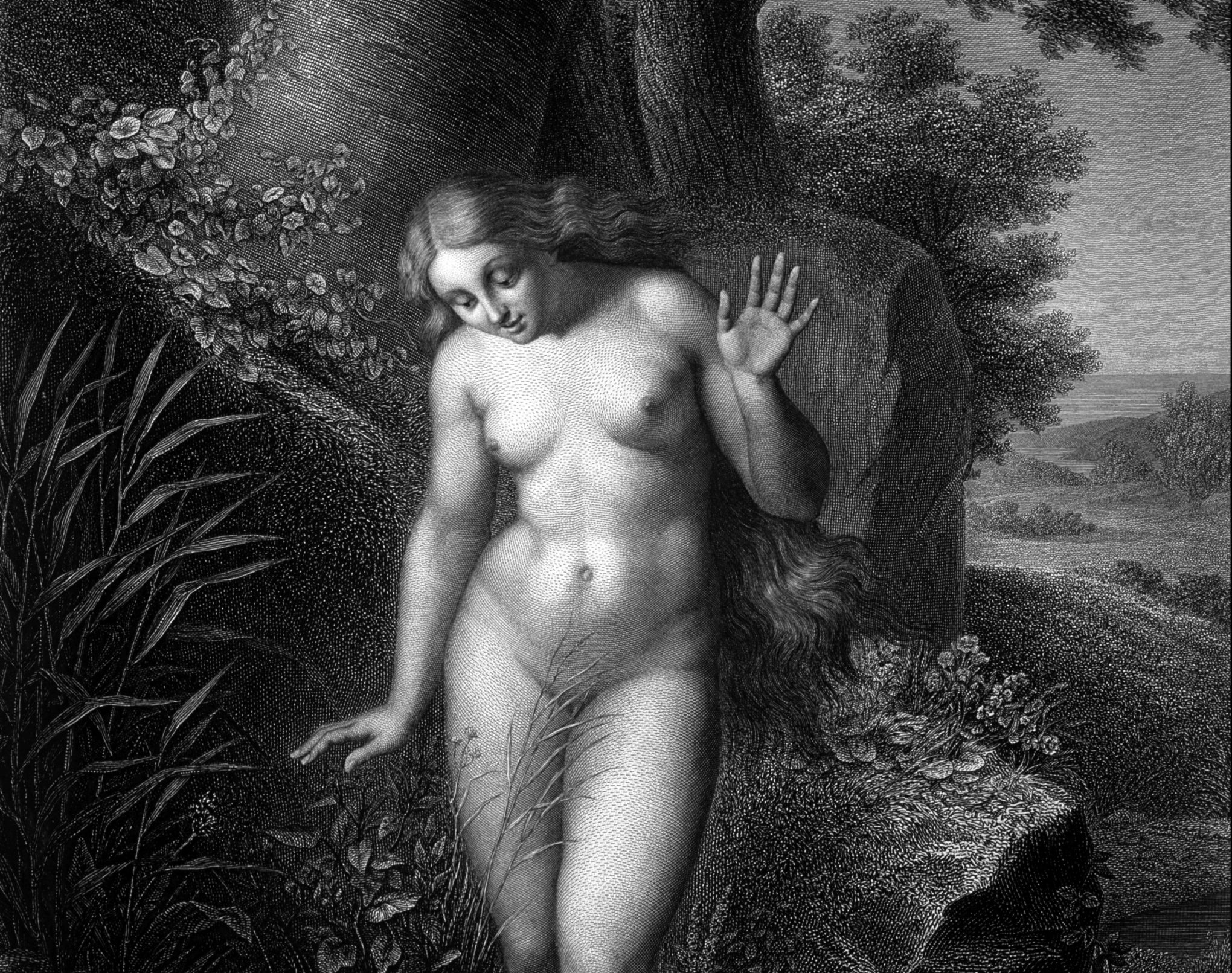

In his younger days, Milton had half-heartedly sketched outlines of an epic poem about the fall of Adam and Eve, lured into destruction by Satan, the ruined archangel. Now that poem was rapidly taking shape, delivered by his muse while he slumbered (he claimed) and dictated urgently each morning to anyone in the household within earshot.

With his ill health and poor digestion, his soul broken by the collapse of his personal fortunes and political dreams, it should have been all but impossible.

But on Ellwood’s return to the cottage from one of his bouts of imprisonment for his preaching, the elderly Milton presented him with the manuscript for an “excellent poem”: his masterpiece, Paradise Lost.

Paradise Lost is, from its beginning, a poem about what it means to be broken. Beseeching his heavenly muse for aid, the blind, disillusioned Milton presents the shattered pieces of himself, and does not ask that they be made whole, but instead that God find in this imperfect instrument the means to work a wonder. “What in me is dark/ Illumine, what is low raise and support,” he implores, so that he might rise to the heights of poetry “and justify the ways of God to men.”

The poem is shockingly raw about Milton’s struggle with his isolation and disability. Like Shakespeare, his griefs seep into his work. What is singular however about Paradise Lost — what approaches the secret heart of its narrative of Christian salvation — is that deficiency and damage become not just the site of Milton’s broken-heartedness but the spectacular engine of redemption.

Paradise Lost imagines a perfect God who creates along a principle of generative asymmetry — a God who, to borrow a phrase from Shakespeare, “by indirections finds directions out,” using the damaged, the infirm and the imperfect as the means of renovation and reconciliation.

Milton’s Adam, perfect and entire, begs God to make him asymmetrical, carving from his side a rib. His Eve is led away from her narcissistic fascination with her own reflection in a pool to find a partner who is lumpier and somewhat dimmer than her, but in whose mismatch she might find contentedness. Most awesome of all, his Son of God elects to descend from his throne to die for humanity, becoming special (and the locus of Satan’s ire) precisely because he is willing to be humbled.

When Milton finally broke his quarantine, he returned to a London ravaged by plague and flames. The Great Fire of 1666 had left the city in ash.

But he had not let despair defeat him; instead, in 1667, Paradise Lost was published — the great work that ought never to have been. Shortly thereafter, he released Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes, about finding the strengths to resist the tyrannies of this world.

I think I have learned from Milton, in spending this terrible year in the solace of his company and that of my podcast’s listeners, that it is possible to find a way to go on after your world ends and all the lights seem to go out. I did not write a King Lear nor a Paradise Lost, but I think I understand a little better the spirit that did, and the grace that lit the way.

The last lines of Paradise Lost illuminate a scene of ruin, but also imagine a path forward, as Adam and Eve depart Paradise. Wiping away tears, “They hand in hand with wandering steps and slow, / Through Eden took their solitary way,” emerging into what Shakespeare, in his own last work, might have called “a brave new world.”

I live in hope to see what kind of people we will be in it.

***

Anthony Oliveira is a writer in Toronto and the host of The Devil’s Party podcast.

This story was first published in Broadview’s April/May 2021 issue with the title “Poetry amid the plague.”

“PARADISE LOST” by Milton has become a horror for the church as we have used its imagery to promote guilt, judgement, ie slavery We have lost Milton’s meaning as shared here.

My brother Festus, the book was politically motivated.

That being said, we need guilt and judgment to be right with God. If we have no guilt, we have no need for God.

If we have no guilt, we have no sin. If we have no sin we don’t need Christ.

We are all going to be judged in heaven, Christians and sinners. (Romans 14:10-12, Romans 2:5-11, 2 Corinthians 5:10)

The imagery used wasn’t the Gospel, but it sure clarifies some of the misconceptions people have about sin, its origin, and the hidden spiritual warfare.

Amen to that. Is it not preferable to have a joyful journey with God? Is it not better to see and appreciate God within all things and all things within God? The concept of sin is a human construct that keeps people in bondage. If we are to progress we must recognize that, yes, we all have human emotions and feelings that are given to us by the Creator and some of us do break the law, go to war and make mistakes. However, we are biological beings in which we have consciousness of self and therefore can rise above the level of animal behaviour if we choose. Religion has been used to perpetrate some of the most heinous crimes and simply believing in Jesus, or the Christ, or the church didn’t stop them. Indeed, it even encouraged them. I prefer a personal spirituality and a personal journey with God. It works for me.

Amen to that. Some of the most heinous crimes in history have been and are being perpetrated in the name of religion including Christianity. Once we understand that religion as we know it is a human construct, we can begin to see that God is in all things and all things are in God; theologian Marcus Borg called this “Panentheism.” Education can lead us to a better understanding of the spiritual journey.

The problem with the philosophy of panantheism is its claim that we can change God. This limits His omnipotence, omnipresence, and omniscience. God surpasses everything He created.