Hassan Rasouli never intended to, but he made history in Canada, and he did it in the most improbable way, while lying in a critical-care hospital bed in Toronto, hovering between what his doctors called “a persistent vegetative state” and “minimal consciousness,” stubbornly lingering on while one court after another methodically deliberated about whether or not to sign his death sentence.

The wait took three years and ended with a Supreme Court of Canada decision last fall that adroitly avoided the basic question — should this man live or die? — first put to the courts by Rasouli’s doctors at the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto. What the court did do was deny Canadian physicians the sole authority to decide when to withdraw life-support from anyone, especially when opposed by family members hoping for miracles. The result left Rasouli in limbo and critical-care specialists across the country fuming in frustration.

With artificial life-support ever more attainable and a surge of senescence about to overwhelm society as the baby boom generation slowly fades out, the ethics of end-of-life medicine in Canada are profoundly unsettled. Rasouli himself remains barely alive, dependent on a mechanical ventilator and a feeding tube, with no hope of recovery from the bacterial infection that ravaged his brain after surgery to remove a benign tumour. And the coming debate about what to do with others like him, according to one of the experts who routinely tread this new netherworld on the very edge of life and death, “is going to make the abortion debate look like a Tuesday tea party.”

But something else was happening while lawyers argued, Rasouli lingered and three courts in a row declined to issue his death sentence. Over the three years it took to not decide the retired engineer’s fate in the courts, an obscure tribunal in his home province of Ontario issued lightning-quick life-or-death judgments in disputes between the families and caregivers of no fewer than nine different intensive-care patients. While the courts struggled, the Consent and Capacity Board — an institution unique in North America — routinely cut through the thorny ethics of ending life.

Consider the case of 84-year-old A.C., who was far closer to death than Rasouli in spring 2013 when his doctors at Hamilton’s Juravinski Hospital entered the end game of a long struggle with his family over his care.

Described as “a lovely patient” by Dr. Corey Sawchuk, the hospital’s chief of critical care, A.C. was fed by a tube, breathed with the aid of a mechanical ventilator and suffered from “end-stage multi-organ system failure” that required dialysis three times a week. Sawchuk recommended withdrawing life-support, but A.C.’s family adamantly refused to consent. Called to the hospital to judge the matter in a quasi-legal hearing, a three-person panel of the Consent and Capacity Board decided he should live, criticizing the hospital’s proposed treatment plan as “unclear, vague and overbroad.”

A few weeks after Hassan Rasouli’s surgery, elderly G.S. of Ottawa almost died in a car crash and never regained consciousness. Unlike Rasouli, however, G.S. had prepared for the worst by swearing an advance directive, known in Ontario as a power of attorney for personal care, that stated clearly, “I do not want my life to be prolonged and I do not want life-sustaining treatment to be provided or continued . . . if I am in an irreversible coma or persistent vegetative state.” Even so, his family demanded “heroic measures” to save him. G.S.’s daughter, his official substitute decision-maker, accused the doctors of attempted murder. But the CCB ordered her to comply with their proposed treatment — which was indeed the withholding of aggressive treatment.

C.A. was only 45 years old but had existed in a persistent vegetative state at Humber River Regional Hospital in Toronto for two years by September 2013, the eve of the Rasouli ruling. Her prognosis was “undoubtedly hopeless,” according to one specialist, her quality of life “nonexistent,” according to another. Repeated entries on her chart emphasized her suffering from bedsores and successive infections even as her family insisted that she be kept alive. C.A.’s family wanted her doctors to administer natural treatments, including chlorophyll and “natural raw foods,” while awaiting the miracle their religion promised.

After a one-day hearing that carefully canvassed C.A.’s own beliefs, the CCB authorized removal of the ventilator that kept her alive. The family appealed to Ontario’s Superior Court of Justice, which upheld the board’s decision four months later.

The board ruled for life or death in at least six other cases over the time it took the ordinary courts to judge the dispute between Hassan Rasouli’s doctors and his wife, Parichehr Salasel. The number is uncertain because some cases are resolved without reasons being published, in which event they never become public. But the cloak of obscurity that surrounds this extraordinary body came off with a flourish when the Supreme Court released its first-ever judgment in a medical-futility case. The court’s ultimate opinion was neither that Rasouli should live nor die, but rather that the Consent and Capacity Board should decide his fate. With that, the Ontario board became the model by which all such disputes will be decided. And as its own activities attest, there is no shortage of these decisions coming our way.

In the public life of the United States, the phrase “death panel” is notorious. First tweeted by right-wing gadfly Sarah Palin in response to an obscure clause in President Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act, it was denounced immediately by sensible observers as an outrageous distortion. And yet it lived on to become the meme that almost destroyed Obama’s signature domestic policy initiative, a chilling three-syllable confirmation of the worst imaginable atrocities of “big government” administering socialized medicine — “killing granny” to save money.

The clause that raised Palin’s death-panel cry, and that was ultimately excised from the legislation, offered doctors a fee to discuss end-of-life planning with patients — a rational policy designed less to cut critical-care costs than to forestall the often tragic confusion and suffering that can erupt in the absence of clear advance directives from elderly patients. But if that’s a death panel, it’s hard to imagine what Palin and her millions of followers would call Ontario’s Consent and Capacity Board.

The CCB has been dubbed a death panel and worse by some of the people who have had the misfortune to require its services. Inevitably, by the time the board is called in, the family’s grief over a loved one’s final descent has been exacerbated by acrimonious disputes between doctors and families, or within families themselves. Only the saddest, most intransigent and medically horrendous cases require a hearing, and combing through the board’s records is a sobering experience. It also reveals, in startling detail, an entirely new frontier in Canadian jurisprudence.

This is what makes the CCB so controversial among doctors, many of whom see it as a direct threat to the founding principles of their profession. Seizing on the Rasouli case to stage a rebellion against the CCB, the Sunnybrook litigants pointedly bypassed the board and went straight to the courts to demand the unilateral right to withdraw life-support from Rasouli. It was an aggressive legal assault against his wife, but the basic argument behind it was an appeal to the status quo that prevails everywhere in Canada outside Ontario — and indeed in most common-law jurisdictions — where no appointed boards dictate policy and procedures to doctors struggling heroically to save lives or, when that’s not possible, at least do no harm.

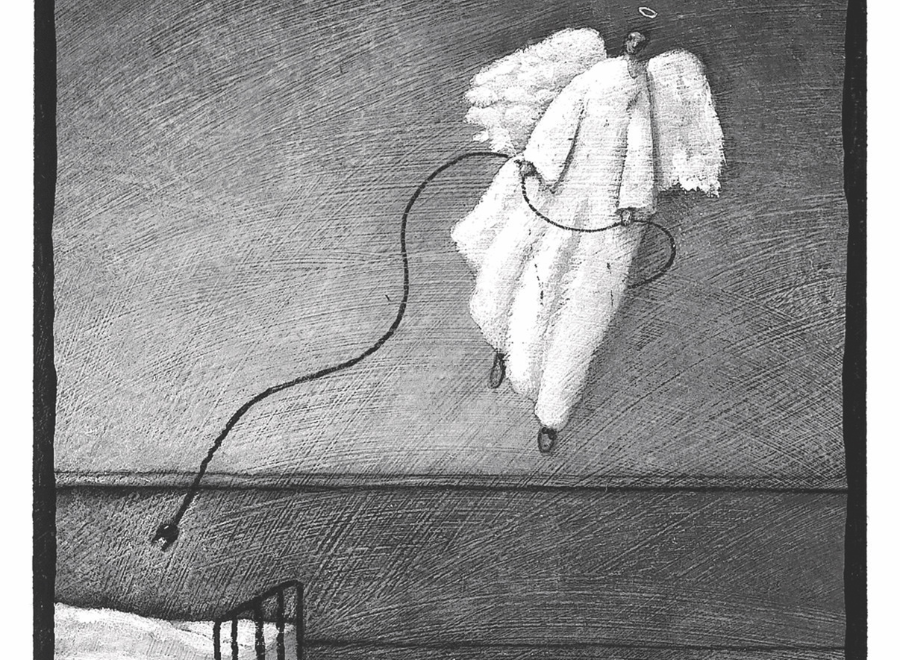

Nobody wants to play God, the doctors insisted. But somebody has to do it, and in that case it had better be us.

Had the courts agreed with them, the CCB would have been out of the death-panel business for good, its groundbreaking activity just another abandoned innovation. But as it turned out, every court in the land disagreed with the Sunnybrook doctors, and the Ontario board became the gold standard for resolving end-of-life disputes in Canada.

The Supreme Court judgment was “a wonderful endorsement” of the board’s work, according to its chair, Judge Edward Ormston. An energetic and genial figure, Ormston is an influential human rights pioneer and past chair of the Mental Health Commission of Canada’s advisory committee on mental health and the law.

Ormston was seconded to the Consent and Capacity Board after spending most of his career as an administrative judge at Toronto’s Old City Hall, the largest criminal court in Canada. There he became increasingly frustrated by the number of mentally ill people getting caught up in the criminal justice system — and often being abused by it. Lobbying for reform, he became the principal organizer of Canada’s first Mental Health Court and an advocate for what is now known as “therapeutic jurisprudence.”

He adopted the motto “Close the book and open your heart” when presiding over hearings of mentally ill people accused of criminal acts. Although the CCB is a creature of carefully crafted legislation — Ontario’s 1996 Health Care Consent Act — Ormston considers empathy the most important characteristic of board members.

The primary purpose of the act was to set out procedures for determining how and when people should be committed to mental health institutions against their will — or forced to accept treatment they are resisting. Rather than psychiatrists making such judgments unilaterally, the act mandated an impartial board to do the job, with each case typically heard by a three-person panel led by a lawyer and including one ordinary citizen along with a psychiatrist not involved with the patient’s treatment.

Cases involving civil committal still account for the overwhelming majority of the more than 3,000 hearings the CCB holds every year, but end-of-life cases have always been a part of the board’s work and are expected to grow as medical technology advances to meet what Ormston describes as the “tsunami of dementia” waiting to swamp North America. Nothing less than a proliferation of death panels will be necessary to save an overburdened state, Nobel-winning economist Paul Krugman half-joked recently.

Death-panel talk south of the border inevitably focuses on health-care costs, but that subject is virtually taboo in Canada, where government has long paid the bill for health care. The focus of debate here, where something close to a Palinesque death panel actually exists, is human rights.

When asked about those people who call the CCB a “death panel,” Ormston questions the inevitable phrase. “What about those cases when we say, ‘The family is right’?” he asks. Although infrequent, such instances demonstrate the essence of the argument that swayed the Supreme Court.

In one of the rare publicized end-of-life cases it decided, the board extended a few more months of life to Desmond Watson of Oakville, Ont., who had spent over a year in intensive care. The board agreed with his wife that Watson’s doctors had been high-handed and hasty in their decision to move him off life-support.

“The medical case was absolutely proven to us, that he had no chance of recovering,” says Lora Patton, the CCB vice-chair who heard Watson’s case. The panel was “absolutely convinced” that he was suffering, she adds. “But we were equally convinced of what he would want to do. And in that case, autonomy and one’s own ability to decide what’s done to one’s body is what rules at the end of the day.”

In every instance, Ormston says, the focus of the board is protecting the rights of patients, in particular those incapable of protecting themselves. But those rights also extend to capable people, who are fully entitled to refuse medical treatment. Ormston tells the story of a trapper from northern Ontario whose leg injury had become septic but who refused the amputation that would have prevented a fatal case of gangrene. His doctors brought him before the board, asking that the trapper be declared incapable and a substitute decision-maker appointed to approve the surgery needed to save his life.

“Well,” Ormston says, “he applied for a hearing in front of us and his testimony was, ‘Yes, I know what’s wrong with me. Yes, I have septicaemia and it will eventually come up my leg and turn to gangrene and I will probably die.’” The panel asked why in the world he would resist life-saving treatment. “He said, ‘I’m a trapper. I live in the bush. If I can’t go out in the bush on my own two legs, I don’t want to do it. I know exactly what this is, and I know how I want to live my life,’” Ormston recalls.

“And you know,” the judge adds, “he was entitled to run his life the way he wanted. He died a year later.”

The resolution of a typical end-of-life dispute in Ontario begins with a physician filing an innocuous-sounding “Form G” requesting that the CCB hold a hearing to determine whether or not a vegetative patient’s substitute decision-maker is acting against the law by refusing to consent to the withdrawal of life-support. In almost every case, the doctors warn that their patient is suffering as a result of life-sustaining measures that have become medically futile but still cause harm. And just as often, the patient has sworn no advance directive and never discussed his or her wishes with family members.

The board is required to convene a hearing within seven days of receiving any application, including a Form G, and to release its judgment the day after the hearing occurs. Although the CCB’s decisions can always be appealed to the courts, where delays begin at months and can extend to years, the hearing itself is often enough to satisfy families that they have done all they could. It’s easier to hasten a loved one’s death when a government panel has weighed your concerns and ordered you to do it.

Rasouli remains remarkable not only because his doctors attempted to bypass the board, but because he lingered throughout the three years needed before the Supreme Court settled the dispute over his treatment. He continues to linger on life-support at Sunnybrook, and whether his case will now make its way to the CCB is unclear. Neither the hospital nor the Rasouli family agreed to comment on his condition or his future for the purpose of this article.

Because there is no equivalent to the CCB outside Ontario, most end-of-life cases in Canada will continue to be heard by courts alone — and most will cost families a fortune in legal fees while ending irresolutely with their loved ones’ deaths.

“The big advantage we have is that we’re objective,” Ormston says. “We don’t know the families, we don’t know the parties, we haven’t been treating the patients, we haven’t had a conflict with any of them.” In a perfect world, he adds, hospitals would do a better job of mediating end-of-life decisions without resorting to the board. “But that means they have to teach mediation skills in medical schools, to let students know that, ‘Doctor, you can’t just say you’re going to terminate treatment. You have to talk to the family, and in fact we’re going to give you tools to help.’”

Dr. Peter Cox, head of the pediatric intensive-care unit at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children, needs no lessons in that art. “It’s very much a part of the chosen career of an intensive-care physician,” he says, “working at the edge of life and death and being able to deal with both.”

Former and current CCB members say that hearing end-of-life cases involving children is the hardest part of their job. Cox doesn’t blink when asked how often his team is required to advise parents that there is no hope for their infant children. “Probably about 100 times a year,” he says.

Cox adds that 85 percent of the children who die in the hospital’s intensive-care unit do so because their doctors have withdrawn life-support. “That’s how children die in the ICU,” he says. “And so a very large part of our practice is advising families that there is no more hope.”

Cox focuses on matters of respect and dignity in helping families reach a point of acceptance. “If you introduce those words to a family . . . they can see that being on a mechanical ventilator and having suction tubes pushed down your breathing tube to keep your lungs clear is not very dignified, nor is it respectful of a child who has no hope.”

When parents balk, the reason is always the same: faith. “Whatever faith might mean,” Cox says. “It’s the belief that a miracle might happen, and in our world that doesn’t happen.”

But nor can religious views be coldly dismissed. “The day I don’t actually feel some kind of pain when telling a family their child’s going to die is the day I should stop doing my job,” he says. “When you lose that compassion, then you do become a death panel, not a person.”

For Cox, one of the potential hazards of the Rasouli decision is that it places an enormous burden on parents at their frailest, requiring them to consent to the final measures that will hasten their child’s death. Other intensive-care specialists are even more blunt in their reaction to the case. “Canadians should have expected better from their court, quite frankly,” says Dr. Laura Hawryluck, a Toronto critical-care physician, trained ethicist and leading authority on end-of-life issues in Canada. In her view, empowering the CCB to override medical opinion — to be the life panel, in Ormston’s phrase — is profoundly wrong. And in reality, she says, the board is far removed from the independent, expert panel praised by the Supreme Court.

The board’s lack of expertise in critical care is embedded in its constitution, which relies on psychiatrists to provide medical expertise at hearings — an artifact of its original focus on the rights of the mentally ill. “But if we’re talking about taking away somebody’s life, which is how the legal system and certainly the public have been looking at this, why wouldn’t you put a critical-care physician on the panel?” Hawryluck asks. To be truly fair and transparent, the board needs experts qualified to question the medical evidence brought before it, she says.

The medical profession’s most profound objection to the CCB is its potential to override principled medical opinion with values that are vague and decisions that are ultimately discretionary. And that matters, says Hawryluck, because life-support by its very nature is hellish. “Because it’s such an aggressive set of therapies, it never loses its ability to harm someone even as it loses its ability to help,” she says. “Our harms are real, and they’re big, and they’re life-threatening in and of themselves.”

Keeping people alive while they suffer the torment of life-support violates the first principle of medicine, according to Hawryluck. “You’re asking doctors to violate their oaths to do no harm,” she says. “You’re asking them to swear it and then to compromise it.”

In the opinion of the board’s critics, the very essence of the CCB — consent — is misbegotten. Doctors do not seek a patient’s consent to cancel a prescription for painkillers when they are no longer necessary, opponents argue, nor should they be required to seek permission from lawyers, priests or devastated families to withdraw futile treatments that are only torturing their patients. Hawryluck worries that religion will override medicine in the aftermath of the Rasouli decision. Others warn darkly of doctors simply giving in and allowing their patients to linger in agony.

In practice, the CCB almost invariably sides with the doctors who file Form G applications, ordering substitute decision-makers to comply with their plan to withdraw treatment. But every tragedy is ultimately its own. Few patterns hold.

L.F., according to CCB records, existed in “a persistent vegetative state” at the Belmont House nursing home in Toronto, “non-communicative for over three years, with minimal brain activity and without prospect of any improvement in her condition,” fed by a tube inserted directly into her gastrointestinal tract. Before her decline, she had sworn a clear advance directive specifying that she not be maintained on life-support in such a state. Her four grown children begged her doctor to let her die. But it was her doctor who refused and brought the matter to the CCB. “The issues we had to consider and resolve here went to the core of human values, dignity and what it means to be human,” panel chair Michael Newman wrote in his meticulous and exhaustive analysis of one particular family nightmare. He and his colleagues sided with the children.

Although the Sunnybrook doctors and their supporters argued that law courts were a better place than the CCB to decide such disputes, it was a court that made the most medically questionable decision recorded in the annals of the board. At 86, F.F. was in a vegetative state at Toronto’s Baycrest hospital when her three children came into conflict with her doctor, who advised that she be let go — in accordance with a living will F.F. had made asking for just that. The children refused to accept the will, citing religious reasons. A rabbi flew to Toronto from New York to testify at the hearing about the beliefs of Orthodox Jews. But the board yielded instead to F.F.’s clearly stated prior wishes.

The children then appealed the board’s decision, and the Ontario Superior Court overturned it. Religion trumped medicine.

This happened because F.F.’s family was able to raise doubts about the validity of their mother’s living will — a common problem and one reason why doctors like Hawryluck put little emphasis on what lawyers and judges call “prior capable wishes.” But in the post-Rasouli era especially, making those wishes known can prevent tremendous heartbreak.

“We’ll never know who was right, because [F.F.] never had those conversations with her family,” says Mark Handelman, the lawyer who represented Baycrest at the hearing. If she had made her decision known to her children as well as her lawyer, Handelman adds, “her children might have said, ‘Mother, this is contrary to your religious beliefs; you have to change it.’ And she might have. Or she might have said, ‘I don’t care what my religious beliefs are; I don’t want to be there. Let me go.’ But we don’t know — and that’s the heartbreak.”

As a former vice-chair of the CCB and a trained ethicist who now specializes in representing parties in end-of-life disputes, both patients and doctors, Handelman levels one major criticism at the Sunnybrook doctors who sued to end Hassan Rasouli’s life. “Why didn’t anybody think to say to Mr. Rasouli, ‘We’re about to slice your skull open to pick a tumour off your brain. We think it will be okay. But in case things go wrong, what do you want?’”

The unexpressed answer to that question is that prior wishes are irrelevant to physicians acting solely on medical grounds and according to medical principles. But they are central concerns at the CCB, and since the Rasouli decision they have become essential to resolving end-of-life disputes in Canada.

“Professionally, neither doctors nor lawyers nor hospitals do a good enough job with the end-of-life questions that patients and clients need to address,” Handelman says. Individuals, too, have endless opportunities to shirk the conversation. “I mean, put your hand up if you don’t think you’re going to die.”

A quick tour through the annals of the Consent and Capacity Board should be more than enough to persuade most people to face reality and make their wishes known. “What can be worse than someone very close to you, a family member whom you love, being in an I.C. [intensive care] bed while you’re having a battle with the treatment team?” Handelman asks. “It’s horrible.”

The Supreme Court put the spotlight on the CCB, and the CCB is responding with a warning: avoid us at all costs. “Please put something on paper with respect to your wishes at end of life,” board chair Ormston pleads. “Please have the conversations with your family. Don’t let three strangers decide your fate.”

But if you don’t heed the warning, those three strangers are fully prepared to do just that.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s June 2014 issue with the title “Playing God?”