“Yahtzee!” cries April Lane when she spots me in the carpool lot off the highway, where I’ve arranged to meet her. “How was your flight from Tor-on-to?” she asks, spelling out the syllables in her warm southern drawl as I climb into the passenger seat beside her and we begin the drive to the town of Mayflower, Ark., about 30 minutes northwest of Little Rock, the state capital.

Lane is likely wondering why I’ve come 1,800 kilometres from Canada to write a story about a sleepy rural town with a population of 2,300. On the surface, there’s nothing remarkable about the place: a few churches and a high school; a tobacco store and a deli; a couple of gas stations.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

We hook into a subdivision called Northwoods. It looks just like any suburban neighbourhood: comfortable new homes, a few cars parked on the street, a basketball net. But almost every house here has a for-sale sign on its neat green lawn. An industrial storage bin sits on one of the yards. There are patches of new asphalt everywhere.

We turn a corner. Lane points a manicured finger at a tree with a dark stain around its trunk. “This entire ditch was completely chock full of oil. It looked like a pool of Hershey’s syrup,” she says. “It’s by no means gone or cleaned up; it’s just covered up. Every time it rains, you can smell it.”

“And this is Ruth’s home,” she continues. “Before the spill, she had a common cold. After the spill, her symptoms got much worse and her doctor diagnosed her with pneumonia.”

People like Ruth have been getting sick ever since the accident. If Lane or anyone else asks why I’m here, I tell them it’s because I’m Canadian and I want to learn more about what spilled Canadian oil is doing to the town and its people.

Early last spring, on March 29, ExxonMobil’s 65-year-old Pegasus pipeline burst in the Northwoods subdivision. Hundreds of thousands of gallons of oil spewed out of a six-metre gash, running down the street and across yards and driveways.

Emergency responders, state and federal agencies and ExxonMobil worked to contain the spill. But after a heavy spring rainfall, oil ran underneath the interstate highway, seeping into nearby marshlands and what locals call the Cove, a small body of water that flows into Lake Conway, a popular fishing spot. Several months later, oily sludge and sheen left over from the spill is still visible on the water.

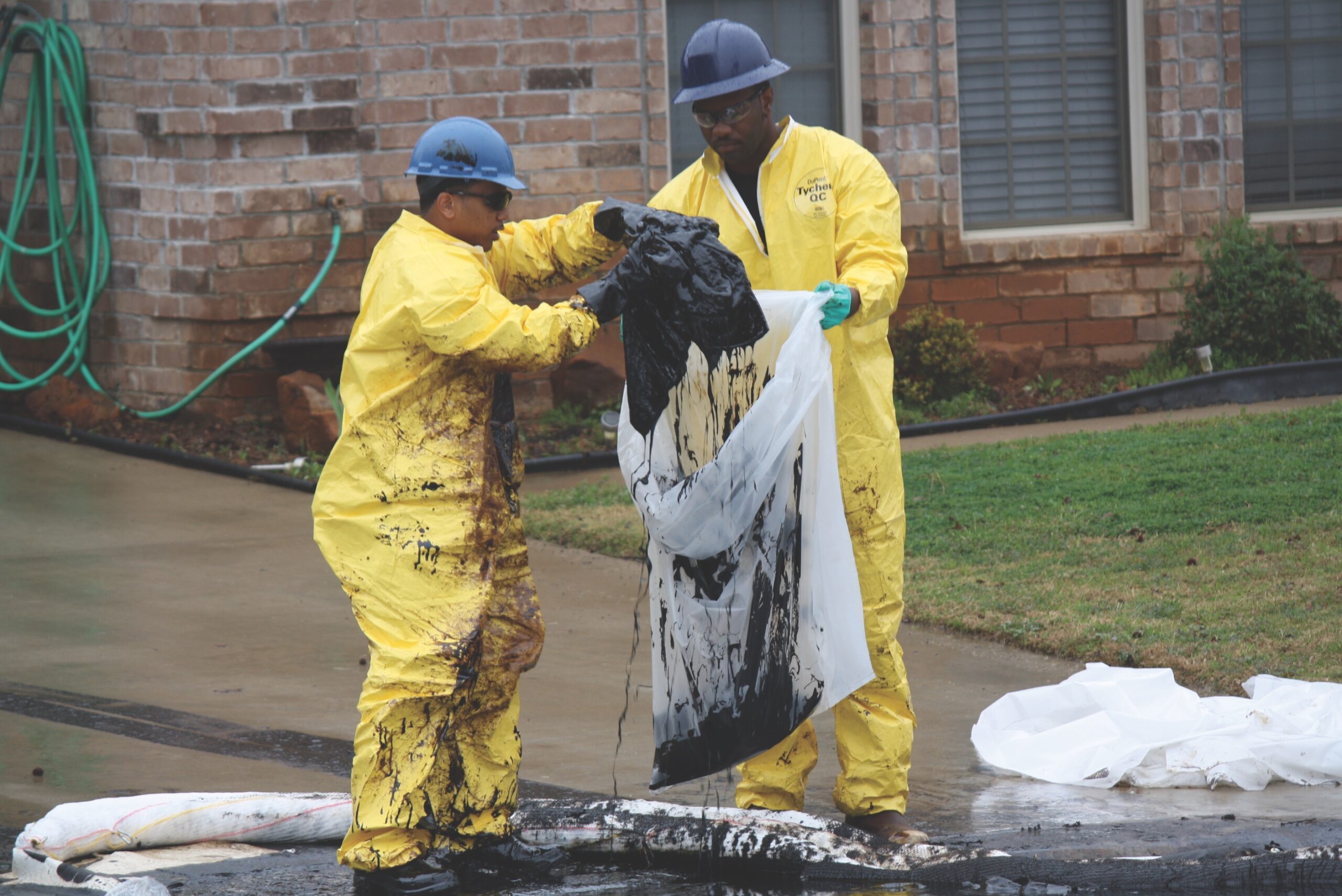

One-third of the 63 homes in the subdivision were evacuated. But none of the people living around the affected area of Lake Conway were told to leave. Some left voluntarily but most stayed, watching as workers in bright yellow hazmat suits worked to clean up the mess.

The pipeline carried 95,000 barrels of oil per day more than 1,360 kilometres from Patoka, Ill., to Nederland, Texas. It’s part of a network of pipelines crisscrossing North America.

The oil it was carrying was Wabasca heavy crude, which originated as bitumen produced in the Alberta oil sands. Bitumen differs from conventional crude oil in that it’s very thick and sticky and requires toxic additives to help it flow through pipelines. These include known cancer-causing chemicals such as benzene. Once bitumen is diluted, it’s called dilbit.

On March 30, the day after the spill, April Lane headed out to the site of the disaster. The 27-year-old college student and married mother of one had been trained in responding to chemical spills as part of her work with a local group opposed to fracking — the controversial technique that uses high-pressure injections to create underground fractures that release buried oil and natural gas. Lane was prepared to take independent air samples of the area using a simple bucket method known as canister sampling.

“I geared up, got my bucket, hard hat, goggles and gloves. The one thing I didn’t take was my respirator,” she recalls.

She drove through the area looking for the best location to take a sample. Remembering her training, she knew to focus on the place where she could see and smell the most oil, but she soon found “there wasn’t a place you couldn’t smell it.” She took her first sample from a ditch along the oil’s path from the neighbourhood to the Cove.

Then Lane started going door to door. She wanted to make sure everyone, not just the people in the homes that were evacuated, understood what they had been exposed to, and that they should report any symptoms to the public health department.

She talked to a mother who was inside her home just across the street from where the oil was flowing. “I knocked on the door, and she said her son had been wheezing and had diarrhea and they hadn’t been told they needed to leave.” Her home was less than five metres from the homes that were evacuated. “She asked me what I would do. I was like, ‘You need to leave.’”

Lane then spoke to a man who had been outside watching some of the workers. He said Exxon had told him not to worry, that they were only evacuating people on the other side of the street because that was where oil had pooled.

Soon Lane started feeling sick. “It was like bubbles in my stomach and intestines. I had a really bad headache, my eyes were burning, and I started dry heaving when I got home. It was bad.”

That evening, she went online and looked up a document called a “material safety data sheet.” Released by Exxon, it lists the chemicals present in the oil and the symptoms people may experience if exposed to them.

“I had almost every single one of [the symptoms] except for death,” she says. “I knew right then, these people were going to be really sick.”

++++

“I took him to the emergency room because he was turning blue,” says Genieve Long, one of the Mayflower residents gathered in Ann Jarrell’s living room to speak about some of the symptoms they are continuing to experience after the spill.

Long is talking about her five-year-old son, who had a severe asthma attack last night. He already had asthma before the spill, but since then it’s gotten much worse.

Outside, dusk is falling but the July heat remains stifling. The cicadas in the trees surrounding the house chirp with an almost industrial intensity. Inside, a fan whirs as the group begins chatting. Instead of the usual greetings, they start by swapping stories about trips to the emergency room, results of blood tests and headaches that just won’t go away.

Long, a 28-year-old college student, has three other children. Her daughter’s asthma has also worsened significantly since the spill. On top of asthma, her son has experienced “skin rashes, vomiting, fevers, headaches and joint swelling.”

Long herself has been ill. Her previous breathing issues have intensified, and “nothing will kick the migraines or the nausea.” She lives near Lake Conway and was not evacuated.

“When I call Exxon, they tell me to call the [state] department of human services, and they [human services staff] tell me to call Exxon. I just get pushed back and forth, and no one wants to take the information,” she tells me as Ann Jarrell distributes glasses of filtered ice water.

Jarrell’s baby grandson and his mother were living with her when the spill occurred. She called the Mayflower police department about the terrible smell and the burning in their eyes and throats. But they told her if she didn’t have oil on her property, she was fine.

It wasn’t until Earth Day, about three weeks later, when Jarrell attended a town hall meeting organized by April Lane and her community group, that she learned about the chemicals her family was exposed to.

“I was in the bathroom crying, calling my daughter and saying, ‘Pack the baby up and get the heck out of my house,’” she recalls.

Her daughter and grandson immediately moved out of Mayflower and into her son’s house eight kilometres away. The seven-month-old baby has suffered from such severe breathing problems that doctors asked Jarrell how many members of the family were smoking around him. “Nobody smokes,” she tells me.

Jarrell, 54, has experienced severe migraines almost constantly since the spill. She has breathing problems, blurry vision and loss of balance.

Everyone in the room that night has a story about a friend, neighbour or family member with similar symptoms. Many have pre-existing conditions that have worsened.

Even Jarrell’s dog is sick. He coughs all night after catching birds he could never catch before the spill. Jarrell believes it’s because the birds are sick too.

“It’s a never-ending battle, and I don’t think we’re ever going to see the light of day on it, I really don’t,” says Jarrell’s 65-year-old neighbour, Linda Lynch. “I didn’t have shortness of breath before all this happened. I can’t even go outside and weed my yard.” She and her son say that Exxon covered the cost of their first few visits to the doctor, but the company is no longer returning their calls. Now they’re having trouble paying their medical bills.

When I reach Exxon spokesperson Aaron Stryk, he tells me that ongoing testing of the air, water and soil in Mayflower shows that all levels of cancer-causing chemicals are either “non-detect” or below the levels that would require action, as established by the Arkansas Department of Health.

Stryk urges residents with ongoing health issues to contact Exxon’s claims department, declaring that the company “will honour all valid claims.”

He says the oil that spilled in Mayflower is no different from ordinary crude and doesn’t require a different kind of cleanup or pose special health risks. He also says that no oil made it into Lake Conway, only the area called the Cove. (Mayflower locals say they’re one and the same.) On health issues, Stryk defers to the Arkansas health department.

Ed Barham, a public information officer with the Arkansas Department of Health, acknowledges that people were experiencing acute symptoms such as vomiting, nausea and impaired breathing immediately after the spill. But he calls these “transitory effects” and says the levels of chemicals showing up in testing done by Exxon, and state and federal agencies, are not levels associated with “long-term illness and disease.”

Barham defends the decision to evacuate only part of the Northwoods subdivision, an action he says was based on the results of real-time air monitoring.

“There are a lot of things that cause headaches, nausea and illness. There wouldn’t be a way for us to connect the illness people are reporting now with what happened in the oil spill,” he says.

An independent air test that April Lane conducted on March 30 showed 30 volatile chemicals present in the air, including benzene and several other carcinogens. The benzene level exceeded air standards for Texas, Louisiana and California. Levels of five other chemicals also exceeded air standards for other states.

The short-term health effects for several of these chemicals, found on the material safety data sheet provided by Exxon, read like a checklist of the symptoms Mayflower residents continue to experience: headaches, eye and throat irritation, nausea, difficulty breathing, gastrointestinal problems, chemical pneumonia, rapid heart rate, blurred vision and loss of co-ordination. Possible long-term effects include cancer, nervous-system damage, birth defects and death.

Lane says the industry regulations are not appropriate because they monitor parts per million and not parts per billion — a more precise baseline that is better for evaluating risk in both the short and long term, she argues, especially for vulnerable populations. And she thinks Exxon and the government agencies should have tested using the canister-sampling technique, which is more sensitive, instead of conducting their initial tests with handheld air monitors. She suspects more people would have been evacuated — meaning fewer people might have fallen ill.

Scott Smith, a scientist and environmental entrepreneur who has worked at oil spills across North America, took about 100 independent samples of the water column of Lake Conway. They tested positive for several toxic chemicals, including benzene.

He says the samples that Exxon and the state and federal agencies are using are only from the water surface and don’t take into account the cumulative effects of the chemicals over time. Every time it rains, the chemicals in the water are stirred up again, he notes. Smith has developed a method for cleaning up bitumen spills, which are different than conventional spills because the oil is heavier and sinks in water. But Exxon told him this method was not needed in Mayflower.

Wilma Subra, a chemist based in Louisiana, has worked with communities affected by environmental threats for over 30 years, including people who experienced similar symptoms after the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. She visited Mayflower for the Earth Day community meeting, where she remembers meeting hundreds of people with symptoms. She came away convinced that these ongoing health problems are “absolutely” linked to the spill.

Subra believes more people should have been evacuated to reduce or minimize exposure, and that more people should be able to leave now if they so choose. “They should be given the opportunity to leave, and Exxon should be covering the cost,” she says.

Exxon has developed a plan to help purchase some of the homes of residents who want to leave permanently, but the assistance is only available to residents in the Northwoods subdivision and not the surrounding areas. And only people who lived in the 22 homes that were evacuated are eligible to have Exxon buy their houses immediately at the pre-spill price.

The flow in the pipeline that runs through Mayflower was reversed in 2006 to carry dilbit from the oil sands. The March spill was not the first time a reversed pipeline has failed.

In 2010, an Enbridge pipeline ruptured in Michigan, spilling over three million litres of heavy Alberta oil into the Kalamazoo River. It was essentially the same kind of dilbit that spilled in Mayflower. Three years later, oil is still being removed from the river, and hundreds of nearby residents have complained about health problems.

Pipelines everywhere are aging. The Mayflower pipeline was 65 years old. The one that ruptured in Kalamazoo was built in 1969.

TransCanada Corporation’s proposed extension of the Keystone XL pipeline to carry diluted bitumen from Western Canada to the southern United States has sparked a lot of debate. But Enbridge also wants to expand its existing network of pipelines in Eastern Canada.

In particular, the company hopes to reverse a pipeline called Line 9 that runs through heavily populated centres such as Toronto and crosses several major rivers and waterways. Until recently, Line 9 carried 240,000 barrels a day of imported conventional oil from Montreal to Sarnia, Ont. Enbridge has already reversed the section from Sarnia to North Westover, Ont., near Hamilton, and has applied for a permit with the Canadian National Energy Board to reverse the remaining section, from North Westover to Montreal.

Line 9 was built in the mid-1970s. With the reversal, Enbridge would boost the oil flow to 300,000 barrels per day and possibly carry diluted bitumen.

Exxon maintains it did all the necessary tests before reversing the Mayflower pipeline; an investigation into the cause of the rupture is still under way. But environmental groups contend that reversing older pipelines to carry diluted bitumen is dangerous and can contribute to ruptures and leaks.

Adam Scott of Environmental Defence, a Toronto-based watchdog group, quotes a study by the U.S. Natural Resources Defense Council: pipelines in the midwestern states that carry diluted bitumen “spill on average 3.6 times more often than the rest of the network.”

The increased spill rate “may be due to the fact that the stuff often runs at a higher pressure and temperature, both of which are factors in the speed of corrosion,” he says.

Scott calls dilbit cleanup “dramatically more difficult” than conventional oil spills and “even more dangerous.” The lighter chemicals added to the bitumen to get it flowing through the pipeline evaporate into a “toxic cloud with nasty stuff like benzene, toluene and N-hexane, which are acutely toxic to people and plants and animals nearby.” The chemicals in the heavier bitumen sink in water, coating the bottom of lakes, rivers and wetlands.

April Lane has lived in rural Arkansas all her life. Her librarian mother and school superintendent father raised her to be “civilly minded.” She still calls herself a conservative Republican, “but not a crazy one,” she adds with a laugh as we dig into sandwiches at a family restaurant.

She says her environmental work is motivated by a love of her state and a desire for a better future for her four-year-old son. She has “a billion recommendations” on everything from the evacuation to the equipment used for cleanups. And she realizes that people in Mayflower are “guinea pigs” when it comes to health effects.

Many local residents are frustrated with their doctors, who aren’t linking symptoms to the spill. “Most family doctors don’t know how to deal with this. They are not in any way trained or have any specialization in chemical exposure. So they’re just at a loss,” she says.

Lane would like the state health department to do a comprehensive study of the Mayflower spill and the symptoms that followed it. The health authorities say they have no plans to do so.

“That’s what my biggest issue has been with this whole thing from day one. We’re missing that huge piece of the puzzle,” she says.

The challenge is to learn from what happened in Mayflower. “When this happens again, to the next town, in the next state, or whether it happens when they turn this pipeline back on, we need to be a lot better prepared,” Lane says. “It’s not when it’s going to happen again. It’s who’s next?”

May Warren is a journalism student at Ryerson University in Toronto and was The Observer’s summer intern.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s September 2013 issue with the title “Did Canadian oil poison this town?”