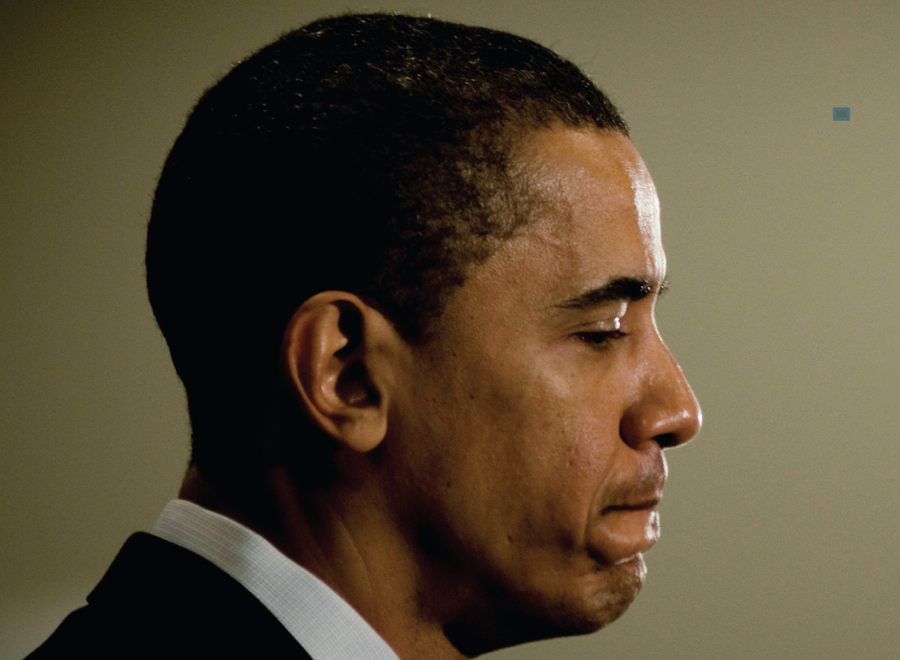

The nagging controversy over U.S. Senator Barack Obama’s relationship to his former pastor, Rev. Jeremiah Wright Jr., and to his home congregation, Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago, might offer some proof that God does indeed work in mysterious ways. For though the controversy was triggered by political hacks and was intended to smother Obama’s presidential hopes, it ended by goading him into delivering a historic speech on race that reignited those hopes. It also goaded Wright into a series of inflammatory public statements that hurt Obama’s campaign all over again and forced him to make a clear break with Wright.

Ultimately, though, this flap over faith, racism and patriotism has given strength to a remarkable congregation that has come to see itself as a co-author of the next chapter in American history.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

In the family of 5,700 congregations that make up the United Church of Christ, Trinity is unique. The church is a large, solid, ochre-coloured structure set in Chicago’s South Side in a rough neighbourhood of bungalows, car repair shops and bleak storefronts. A block away sits the tiny church that Wright, as a young exponent of Black liberation theology, inherited 36 years ago, along with 87 parishioners.

Under Wright’s dynamic guidance, the Trinity congregation swelled to over 8,000, making it the largest single church in the 1.2 million-member denomination. It operates dozens of ministries and outreach services, the busiest of all, lately, being the communications ministry, which has had to create strict protocols to protect the church’s sacred space from intrusive media attention.

Trinity describes itself as “unashamedly black and unapologetically Christian,” and proclaims among its core values a “non-negotiable” commitment to Africa. But charges that it is a “racist” church with a “hate-mongering” pastor quickly fade when you visit the church and talk to parishioners.

Attending a worship service at Trinity is an extraordinary experience. A choir of more than 100 singers dressed in brilliantly coloured African robes banks one end of the bright, angular sanctuary. The congregation, packed into the main floor and three broad balconies, includes people from all backgrounds. A small seven-piece orchestra accompanies the singing and punctuates the proceedings with lively incidental music tinged with gospel, soul and blues. The three-hour service is filled with laughter, shouting, clapping, hugging and hand-holding. The congregation radiates such a powerful and open sense of community that it’s hard to believe it has become the target of so much vilification.

The church’s current trials began this past March, just before the start of Holy Week, when the American mass media began broadcasting tape clips in which Wright is seen histrionically calling on God to “damn” America and suggesting that the 9/11 attacks were “payback” for America’s violent foreign policy. Trinity was quick to post longer versions of the sermons on YouTube that provided some context for Wright’s remarks.

But the controversy continued to grow, and it thrust Trinity into the spotlight at a time when it was least prepared to deal with it. Wright was set to retire and his successor, Rev. Otis Moss III, who had been on staff for eighteen months, was scheduled to give the Palm Sunday sermon. Journalists descended on the church, seeking interviews with parishioners and disrupting worship services. Hate mail poured into the church along with a few death threats. The distress this caused the congregation was only partly assuaged by expressions of solidarity from other United Church of Christ congregations.

Moss turned to some Trinity members for help, including Linda Thomas, who teaches at the Lutheran School of Theology in Chicago, and Dwight Hopkins, a theologian at the University of Chicago. They advised him to respond boldly. On Palm Sunday, Moss delivered a stem-winding sermon on the Crucifixion that spoke directly to the controversy. “It may seem that we are being crucified,” he told the congregation, “but I’m here to let you know that they are just lifting us up, to give us an opportunity to speak love into this situation.” Both Hopkins and Thomas felt that their new pastor succeeded at turning the crisis into a moment that both affirmed his leadership and brought a sense of purpose to the congregation’s distress.

Two days later, however, the drama of the Trinity controversy was overshadowed by Obama’s own response, his “A More Perfect Union” speech delivered in Philadelphia, near where the Declaration of Independence was signed. The speech has been called everything from a brilliant fraud to a historic address that can stand beside the sermons of Martin Luther King Jr.

Understandably, the response of many of Obama’s fellow parishioners was more nuanced. Though they hardly needed to be told, they were nevertheless thrilled to hear him say that America’s “original sin” was slavery, and by his daring call for a national discussion on race. Some were bothered by Obama’s firm rejection of Wright’s views on racism, and Wright’s own responses have appeared dismissive of Obama. (“He’s a politician; I’m a pastor,” Wright told current affairs show host Bill Moyers on PBS in late April. “We speak to two different audiences.”)

But what really caught the attention of people like Hopkins was how Obama’s language confirmed his identity as a Black American. In a country where racism is still alive, Obama said the remarkable thing was not how many had failed in the face of discrimination, but how many had been able to “make a way out of no way” for those who followed.

“Most white people missed it; most Black people went crazy,” Hopkins said. “That phrase, ‘Make a way out of no way,’ goes right back to slavery. Every Black church in America knows what that means. That’s how we got over. Grandma made a way out of no way. God made a way out of no way. I was like, ‘Oh my God, did he say that?’”

Trinitarians, including Hopkins and Thomas, believe that Obama’s membership in their church, far from being a liability, is a major source of his power and persuasiveness as a presidential candidate. Without the mentorship of Wright, who brought a skeptical Obama to the faith, and without the intense, family-like atmosphere in the church and its commitment to community action, they feel that Obama may never have fully understood the Black experience in the United States.

“He grew up away from the mainline African-American experience,” Thomas says. “Trinity United Church of Christ gave Barack a sense of African-American culture embedded in the Black church.” And she says that Wright’s recent statements, far from damaging Obama, were a powerful corrective to media misrepresentation of the Black church in America.

“Many media and political pundits . . . do not understand religion and especially the historical African-American church. The other thing they will not understand is that Dr. Wright is speaking in defence of the African-American church and not against Obama. Can we not have two different conversations going on at the same time?”

Thomas believes that Obama can carry the debate over race and its destructive place in American society onto a national plane. For her, this means that Barack Obama and Trinity church are part of God’s plan to transform America in a way that African Americans — and others — have been dreaming of and working toward for centuries.

“I believe that God is working the healing of the nation through Trinity United Church of Christ,” Thomas says. “This church has put forth a presidential candidate. And we believe he will win.”

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s June 2008 issue with the title “A way out of no way.”