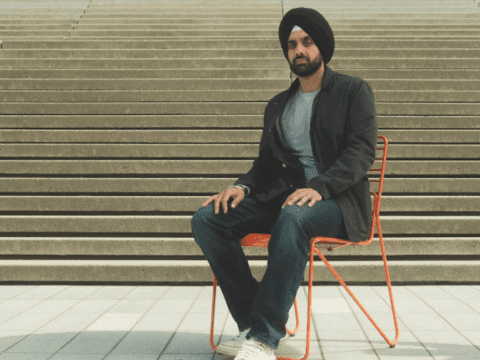

As the COVID-19 pandemic began to take hold four years ago, the pressures of being an emergency department physician in Toronto started to grow for Dawn Lim. In writing this prose poem, and in creating these photographs of two colleagues that accompany it, she explores avenues for healing. Each of the three doctors holds an unusually privileged position in society, often called to navigate decisions about life and death. But each of them — like so many other women — also struggles to balance work with other life responsibilities, particularly those of motherhood. Women in earlier times wore corsets to fit the mould of society’s expectations. In her prose poem, Lim uses the word to echo the less visible complexities of being a woman today. It’s rare for the rest of us to hear the interior dialogue of the physicians who take care of us in such intimate ways, or to catch a glimpse of their vulnerability. Here, Lim offers both.

***

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

We are emergency doctors. We are also mothers. Four years ago, you called us superheroes. While the sounds of banging pots and pans have faded, the voiceless pain is still here, growing unchecked in a healthcare system that ignores our story.

It is my story.

My badge says “MD.” I’ve done the hard work to get here. Though I introduce myself as the doctor, somehow you can still assume I’m not one.

The number of patients waiting to be seen flickers on the screen: 13, 27, 42. You’ve been waiting a long time. Our team is trying to make something out of very little here. To help, I will take your urine, walk you to X-ray and get you a sandwich. No need to thank me.

You don’t thank me.

My heart reaches out to you with each act of kindness. Do you see me?

It is Eileen Cheung’s story.

“Expectations at work [are] that I am professional…even when someone swears at, yells at, threatens or spits at me,” says Cheung. “I am not allowed to be a human being.”

She has spent nine years as an emergency physician in Toronto. She felt like a quitter when she left for her second maternity leave four years ago as the pandemic was just being declared a global threat.

When she came back a year later, the emergency department was unrecognizable. Low morale. Collective burnout. Nursing shortages. Chronically underfunded social programs were overwhelmed by the pandemic. When people could not meet their basic needs, they went to the only place that wouldn’t turn them away. Sometimes they just needed a place to stay warm. “Instead of feeling I made a difference each time I went into work, I dreaded each shift.”

For Cheung, burnout led her back to art as an act of self-compassion. Sleepless and isolated by COVID-19 from accepting outside help, and wanting to celebrate her newborn daughter’s milestone months, she returned to painting. The pandemic allowed her to deeply reflect on her choices in medicine, in art and how she parents. She booked a sabbatical.

“If I hadn’t taken some time away to figure out how to work through this, I was considering leaving medicine forever.”

More on Broadview:

It is Jennifer Hulme’s story.

Hulme is an emergency doctor in Toronto as well as an advocate for those suffering from substance use and homelessness. So many identities.

She also has long COVID.

She looks healthy. Look carefully. She’s wearing compression leggings under her scrubs that squeeze her like a corset. A neck brace presses on her jugular vein to alleviate the palpitations and lightheadedness she gets when she stands. After being away from emergency medicine intermittently for one year, Hulme now works half-shifts. Four hours in, she is depleted. Recovery after each shift is slow with her brain fog. Misunderstood by doctors and the public alike, “long COVID is an invisible illness that nobody really wants to deal with at scale,” she says.

“I hear people whisper about why I’m not working in the emergency department when I can work at a clinic,” Hulme says.

She cannot run after her son.

“My husband is the primary parent now,” she says as she gazes out the car window.

I am a mother.

I’m worried that if I can’t juggle all of my roles perfectly, people will think I’m a bad mother. That’s why I can’t let go of control. I call it efficiency.

I sign field-trip forms. I buy presents for all your teachers. I correct homework. You practise your speech in front of me while I tackle laundry, then press your cowlick down. The lunch boxes are heavy with nutritious foods. I’ll troubleshoot your problems even when I’m in the bathroom. I will study the school curriculum so that I can home-school during lockdown.

It will all get done.

And yes, some days I yell.

We mothers/doctors are your team. Present, but often invisible.

But we need a break too. We need air.

***

Dawn Lim is an emergency physician, writer, photographer and mother in Toronto.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s January/February 2024 issue with the title “Invisible Illness,” where it is available in full.