When I started researching my book Praying to the West, a travelogue of Islamic communities rooted in the western world, I knew that a trip to Chicago was inevitable. It is, in the truest sense, a Black Mecca. It has spawned or galvanized the most consequential African American Muslim groups, most notably the Nation of Islam, the controversial Black nationalist sect headquartered in the Windy City since 1932.

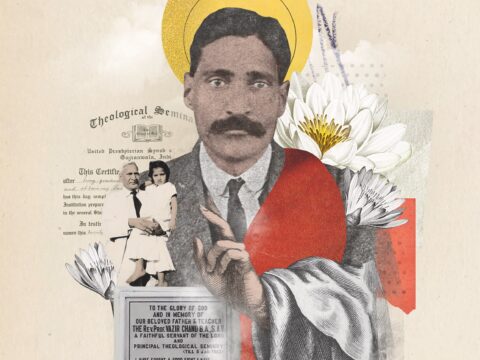

I assumed my story would begin with the Nation’s enigmatic founder, Wallace Fard Muhammad, before tracing his influence on everyone from boxing legend Muhammad Ali to the revolutionary Malcolm X to the first Muslim U.S. statesman, Keith Ellison. But I quickly learned that “Master Fard” himself once had a teacher, Noble Drew Ali, a man even more mystifying and arguably more consequential. Ali was the first American to tailor Islam to the conditions of Black people. And while his early 20th-century movement was always an outlier, he planted a seed that would see African American Islam grow in vigour and numbers, counting around half a million converts today across various branches. Few of those would be likely to recognize Ali’s name or influence. But his obscure take on the Muslim faith hasn’t faded away — on the contrary, it’s enjoying something of a revival. I wanted to find out why.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Most scholars identify Ali as one Timothy Drew, an orphaned North Carolinian who discovered Islam somewhere in the U.S. northeast and founded the Moorish Science Temple of America sometime between 1913 and 1925. However, a recent book by historian Jacob S. Dorman says Ali was John Walter Brister, a Broadway child star and enigmatic circus performer who faked his death and reinvented himself as a Muslim prophet in Chicago.

Ali, of course, told a different story. He taught followers he’d discovered a forgotten section of the Qur’an in North Africa, after a high priest of Egyptian magic had identified him as the reincarnation of Jesus and all other prophets. Ali’s scripture, the Holy Koran of the Moorish Science Temple of America, often called the Circle 7, professed that there is “no negro, black, or colored race.” African Americans were actually undeclared Moroccans, via ancient Muslim Moors.

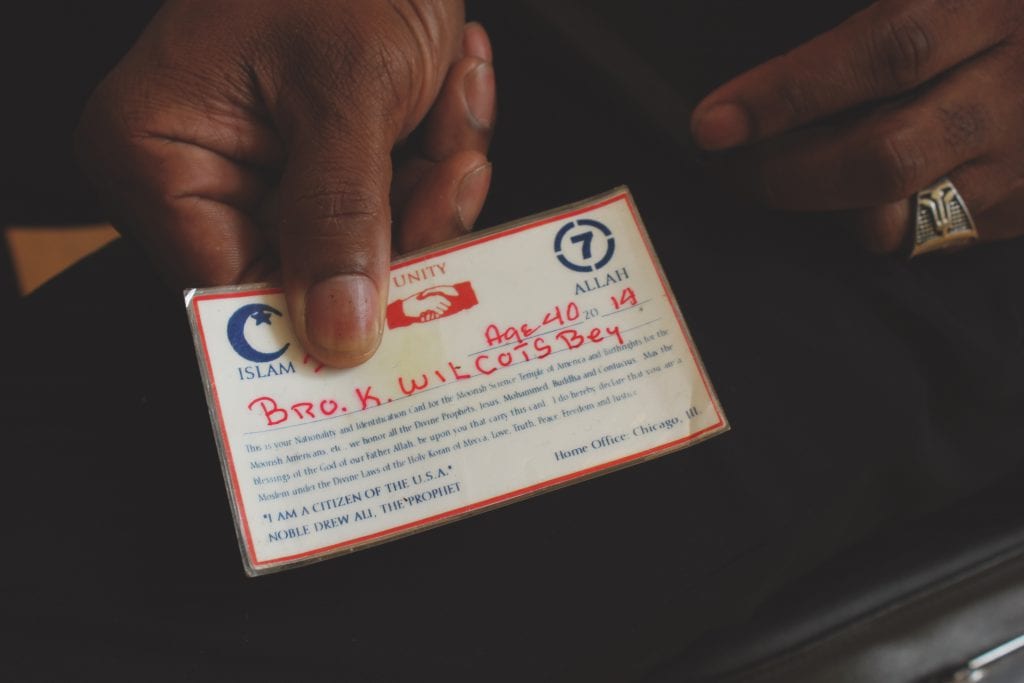

Curiously, Ali’s version of Moorish civilization bore little resemblance to that of any textbook. He told of a kingdom indigenous to northwestern and southwestern Africa and the Americas, and that still ruled over Morocco. As native Moors, he and millions of others were thus exempt from American segregation laws, so long as they had the right identity papers, which only Ali’s temple could notarize (for a small fee).

Studied in tandem with the 1786 Moroccan-American Treaty of Friendship (the United States’ oldest unbroken treaty with a foreign nation), Ali’s teachings convinced thousands that they could break the shackles of white supremacy by taking his legal oath of Moorish American identity. It was both Black nationalism and denial; Ali’s acolytes sincerely believed that they’d never be true citizens — and therefore free of abuse and mistreatment — until proclaiming Moorish nationality.

It’s easy to see why his ideas connected a century ago amid high levels of immigration and ethno-nationalism. Harder to see is why thousands of Americans today are embracing Ali’s spiritual and nationalist beliefs.

Moorish Science was considered a dead religion until a crop of websites emerged in the last 15 years, showing that it’s extremely alive. Or, at least, extremely online. As my research of Moorish Science moved from scholarship to social media, I realized the internet was populated with high-ranking Moorish clergy. These “sheiks” and “sheikesses” don Moroccan-style headwear and insignia jewelry, maintain antiquated spelling and pronunciation of “Moslem” identity, and engage in spirited debate about a faith long thought defunct. Moslems are divided on the forbiddenness of intoxicants and pork, and even on the month of Ramadan. Rather than following the Islamic lunar calendar, many Moslems celebrate Ramadan in October to commemorate the first annual national convention hosted by the Prophet Noble Drew Ali less than a year before his death.

And of course, nothing is more contested than the legitimacy of one branch over another. Some claim to study under a rightful successor to Ali or deem themselves the true Supreme Grand Sheik among many imitators.

While Moors have organized successful civic campaigns with real-life consequences (such as writing themselves into census surveys, which counted over 4,000 Moorish Americans between 2011 and 2015), their online presence looked more like performance art to me. Could I meet a Moslem in real life?

Although missions and temples are widespread, including in Toronto, only one city is called the Moorish Mecca. I flew to Chicago twice in 2019 to join worship services, attend the 92nd national convention of the Moorish Science Temple of America, meet four Supreme Grand Sheiks and try to understand the modern appeal of Noble Drew Ali’s holy message.

The first temple I visited was on Chicago’s East 79th, a tough street immortalized in raps by Kanye West and many others. A quiet middle-aged man wearing all red, from fez to sneakers, stood in front of the handsome old building, selling cups of ice and syrup to passersby on a sweltering June day. He introduced himself as the assistant to Supreme Grand Sheik Kenu Umar Bey, and invited me to wait inside while he summoned the chief.

The temple had the air of a Masonic Hall. Moroccan five-point stars decorated the ceiling, while the walls were adorned with Islamic calligraphy, vintage photos and an enlarged replica of the Divine Constitution and By-Laws, a set of rules that read more like doctrine or prophecy.

Umar Bey finally emerged from a doorway bordered by a collection of swords and hand tools. Youthful for a man in his early 60s, he wore light-blue jeans and a tilted black fez. I had many questions for him, starting with why the internet was suddenly popping with Moorish literature. Had an obscure history simply stumbled into the internet age?

“We call it one of the Moorish hadith,” he said, using an Islamic term for the sacred teachings and sayings of Prophet Muhammad. “These are the sayings of Noble Drew Ali, that in the year 2000 the Moors will come into their own.”

From what I’d deduced, growth began around 2005, incidentally the year YouTube launched. But that’s beside the point. I wanted to know what motivated someone to proclaim Moorish nationality, carry a Moorish ID card and brandish the Moroccan flag more than 50 years after the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibited racial discrimination in voting.

“Our nationality is our nature,” Umar Bey said with brewing intensity. “A rose is a rose, and an apple is an apple. A Moor is a Moor, a Korean is a Korean.” But a European, he continued, is “not white. You can forget that — that’s a status. I’m not Black — that’s the status.”

I didn’t get a lick of it, and yet there was something refreshing about his brand of identity politics, the emphasis of nationality over complexion. Race and colour are hardly windows into individual minds. One’s cultural history is, at least, a good start.

But Moorish beliefs are also predicated on pseudoscience. In Ali’s doctrine, our nationalities and tribes fall into two categories, “Asiatics” and “Europeans.” The former, comprising Turks, Arabs, Asians, Africans and American Indigenous — what we would today describe as people of colour — are natural Muslims prepared for this earth by Allah, Jesus and Muhammad. The latter — what we would call white — invented Christianity in hopes of salvation.

I asked Umar Bey where that would leave me, with my Lebanese ancestry.

“I believe and I know for a fact that we have the same bloodline,” he said.

I started to explain how my ancestral homeland, this tiny continental passageway between East and West, was repeatedly invaded by Armenians, Grecians, Romans, Ottomans. “I actually have probably quite a bit of European heritage.”

He was shocked by my self-debasement. “Why would you say that?”

“Because it’s been conquered by Romans and conquered by —”

“I see your forehead,” he interrupted.

“What?”

“You have a wide, flat forehead. You don’t get that in a European.… You have a nose. You don’t have a pencil. You have lips.”

“I do have lips,” I said with a laugh.

“I’m not trying to be funny, man! When you laugh, look, your cheeks go up. You don’t smile and your face still flat.…You Asiatic — bottom line.”

I couldn’t dispute his observations. Nobody had ever described my face so accurately. But my olive skin seemed like a solid indicator of some “European” ancestry.

Truthfully, it was hard to make sense of his beliefs. I was more drawn to his personal relationship to the faith and what “proclaiming” his nationality had done for his self-esteem.

Umar Bey embraced Moorish Islam in 1976, the year that Jeff Fort, head of the Almighty Black P. Stone Nation, a massive Chicago street gang, reinvented himself into a Moorish faith leader. (Authorities say it was simply a tactic to give the Stones cover.) Umar Bey credited the group for his enlightenment as a young Stone. “I don’t want to say it was like winning the lottery — that’s materialistic. It was like saying, ‘Wow, I got my skin back.’”

In other words, Moorish Science gave Umar Bey ancestral glory. This was echoed later by one of his students, rapper King Zakir. “The power that’s behind that wisdom,” he told me, “it does something to you immediately.” Discovering these ideas felt like uncovering a lost scroll about himself.

“There’s so much propaganda that we don’t know where we’re from,” said Zakir. “I knew I wasn’t Black. I knew I wasn’t African American.”

The sense of history, and self, that was lost in the transatlantic slave trade might be the most difficult trauma to heal. Noble Drew Ali must have known that when he began to evangelize his alternative history and notarize Moorish ID cards. His genius was understanding that self-knowledge dignified a man or woman.

But Ali was extremely controversial within his community. According to reports at the time, Ali built temples in four states, gained 12,000 followers and amassed hoards of cash before his power began to unravel in 1929. One of Ali’s closest aides went rogue and split off with several followers, until a team of men killed him in a suspected hit. Detained with others for the murder, Ali was eventually released on bond and died weeks later.

The coroner listed tuberculosis and pulmonary hemorrhage as the cause of Ali’s death. But some speculated that he’d been murdered in retribution or had succumbed to internal trauma from police brutality. Newspapers reported police abuse but also that the fallen leader had scammed a fortune from his followers and had two wives, one of whom was a minor.

These scandals hindered the efforts of acolytes to maintain the temple after his death. A further challenge was the number of new offshoots and impersonators tussling for his leadership, with more fatalities to follow. Membership fractured and went underground following this implosion, with some Moors gravitating to Wallace Fard Muhammad, who claimed to possess Ali’s reincarnated spirit as he started the Nation of Islam.

“There’s so much propaganda that we don’t know where we’re from. I knew I wasn’t Black. I knew I wasn’t African American.”

Rapper King Zakir

Moorish Science seemed largely dormant when Jeff Fort reactivated it 45 years later, but his offshoot was also short-lived. In 1986, the FBI implicated Fort in a terrorism-for-hire sting involving Libya. Despite the brevity of his new movement, it’s apparent that Fort — currently serving a 168-year sentence — preserved Moorish Science for future generations.

Rasul Hasan Bey touched on this during an impassioned Friday sermon in June 2019. “Moorish Science and Islamism is not something new,” said Hasan Bey, who is now the grand sheik at Temple No. 5 in the Chicago suburb of Gary. “It’s not something made up in the early 1900s or something Jeff Fort ‘discovered.’ This was something he took, and brandished, and utilized in his own temperament, and used as he saw fit, but there was a time before Jeff Fort and the Black P. Stone Nation.”

Hasan Bey became vaguely aware of Moorish beliefs growing up in a neighbourhood associated with the Stones. His search for sincere religion brought him first to the Nation of Islam, and later to the Moorish Science Temple in 2004. His family’s temple observes many common Muslim traditions, including Ramadan, but they’ve struggled at times for recognition as legitimate Muslims. An attempted partnership with an interfaith group was thwarted by orthodox members. “We were trying to show them that we have more in common than [not],” he told me. “We are as much an Islamic group as the next.

Shortly after arriving at the 92nd national convention of the Moorish Science Temple of America in September 2019, I learned there was another convention hosted by a duelling temple only a few kilometres away. It was there that I committed a grave sin.

I uttered the term “African Americans” in a private conversation about the purpose of my research. Word got out, and I was publicly reprimanded by the temple’s Supreme Grand Sheik. “Are you calling us African Americans in this book?” he asked, stamping his finger on my ledger. “Because we’re not African Americans. And if you do that, we’re not participating.”

“You’ve got to understand,” one of the more sympathetic Moors said, “this term — ‘African American’ — is actually a sin for us.” The man suggested “Americans of African descent.”

“We are as much an Islamic group as the next.”

Grand Shiek Rasul Hasan Bey

Fair enough. In a world obsessed with colour, I could see what a burden it would be to stake your ancestral heritage on the back of a vague word. But, like any secular outsider, I struggled to grasp how they reconciled their scripture with modern discourse.

Believers fell into one of two groups called “civic Moors” and “temple Moors” by each other. The civic Moors nitpick about constitutions and declarations, and might view temple Moors as a bit too dogmatic. The temple Moors are into “energies,” mysticism and Orientalist fashion. Their prejudices against civic Moors stem from those who take their Moorish citizenship to extremes.

A cursory search in Google News brings up regular headlines in which self proclaimed Moors are charged for violating local traffic and property laws in eccentric ways: producing fake Moorish driver’s licences, disobeying eviction notices on convoluted grounds or attempting to usurp properties using bizarre legalese. As a result, the Southern Poverty Law Center, a U.S. non-profit that monitors homegrown extremism, designated Moorish sovereign citizens as an extremist group. The centre compares them to the better-known movement of predominantly white libertarians who claim to be sovereign citizens unbound by government laws.

Karima Hasan Bey, Rasul Hasan Bey’s wife and chair of their temple’s grand body, told me the anti-government faction has become a problem even in their city. “There are a lot of people who are looking for truth,” explained the utility company executive. “Unfortunately, you find a lot of misinformation, and you have to go through some hoops to get where you really need to be.…There are a lot of offshoots of the Moorish Science Temple that are just so bogus.

Between the conventions and other temples I visited, I met dozens of Moorish Americans: teachers and entertainers, nurse practitioners and alternative healers, former marines and paralegals. Only one young man professed any belief in sovereign citizenship. It was more common that members entered the temple through an interest in sovereign citizenship. Some were “saved” by the faith community after flirting with the movement’s fringier elements online.

One such man was poised to become the tenth Supreme Grand Sheik, at least of his Supreme Grand Council, which oversees temples and missions in Illinois, Ohio, Florida and more. I met Keith Dandridge El at the first national convention. Modest and mild-mannered, the 38-year-old engineer from Toledo, Ohio, had invited me there without informing me about his inevitable appointment.

He bored quickly of my questions about Moorish politicking and constantly circled back to practice and theology. “Our authority states that we teach the faith of Muhammad,” said Dandridge El, who practised Sunnism throughout his late teens and early 20s. “When I began to read the literature of the Moorish Science Temple and the Moorish Qur’an, it really tripped me out how parallel it was to the Qur’an of Mecca.”

His belief in Abrahamic prophets and traditional family values did not change when he joined the temple. What did, dramatically, was his sense of national heritage. “The only thing that we need to do is claim our nationality in order to be equal and free,” he said.

Even as the world wakes up to systemic anti-Black racism, many Moorish Americans, including those who think their prophet was killed by police brutality, wholeheartedly believe that constitutional rights are not guaranteed to any self-identified Black or African American.

“Noble Drew Ali emphasized that anybody who identifies by these terms will be misused, abused and molested by the other citizen,” Dandridge El told me when we spoke again in light of last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests.

Of course, there’s plenty of disagreement. “When I get pulled over by a police officer, he doesn’t care what I call myself,” Rasul Hasan Bey recently told me. “I think the Black Lives Matter movement was great because it causes our people to think on a higher plane of existence and to be better citizens.… No matter what they call themselves, they’re still our people. It’s still the [same] atrocities.”

He added, “The prophet [Ali] said himself that if you have race pride, then join this Moorish divine and national movement. So we can see the race pride of our people picking up.”

I understood why Ali’s first followers would proclaim their nationality to free themselves from the constraints of 1920s racism. I understood, too, why teenagers in the 1970s thought joining a Moorish gang might free them from poverty. But how could Moorish Science empower them today, in the midst of the biggest civil rights moment in their lifetimes? Of what does it free them?

I thought again about the pejorative I’d accidentally uttered and that gently suggested term, “Americans of African descent.” How would I feel if my primary heritage was reduced to a colour or continent comprised of dozens of nations and thousands of ethnicities? Lebanese evokes a history, a food, a music. Arab denotes a language, an empire, astronomy and mathematics.

Pan-Africanism should have the same power. But for so many of us, “Africa” does not conjure sophisticated Yoruba kingdoms or ancient universities, and barely a word about the true Moors’ glorious history. Too often, it’s slavery, mystery, misery.

“I had no idea I was connected to so much grandeur because I was raised with the mentality that ‘I’m Black, my history is slavery.’ Being recognized is very important,” said Dominic Pettis El, a young Moor and father. “When you’re reminded of your illustrious history, you have confidence to speak to anyone of any nationality, and now come to the table of nations to express your culture, and who you are, and that you came with a sense of dignity.”

***

Omar Mouallem is a writer and filmmaker in Edmonton. A version of this essay will appear in his book Praying to the West: How Muslims Shaped the Americas, due out in September.

What an interesting article.

The Moors strike me as a Islamic cult who are reacting against “white supremacy”.

Interesting that being “black” means your heritage is based on colour.

However, being “white” means I’m European. A continent my great great great ancestors came from, but the other side of my heritage is Asian without the “perceived” features.

The Moorish Science Temple of America, doesn’t teach hate in any form or fashion, it just elucidate the misnomer the was ascribed to Nation of the people that were being called the names of negro, black, and colored, as one is derived from the other, Our names were stripped away in 1774 in a secret meeting of the continental congress on 6th and chestnut st Philadelphia pa, and it was officially placed on the books in 1779 therefore, placing us outside of the constitutional protection that was afforded to citizens in the Articles of Association in 1774,relabeling us as chatel property and thus removing us from citizenship, Islam as brought and taught in the temple helps us to grow and unfold into true American citizens, ready to contribute any talents that we can to the betterment of the nation, because we are a part and a partial of the government, so learn more before speak about something that you aren’t truly informed of, have a great day✋🏾Peace!

***Correction*** Master Fard Muhammad was never taught by Noble Drew Ali, that’s a Moorish fable.

Hi there, this claim is backed up by our research. Feel free to let us know if you have other sources! Best, Emma

And I also agree that Wallace Ford, as well as Elijah Poole and his brothers were members of Temple#4 in Detroit

Islam Mo’… care to elaborate on why you agree?

This was an interesting Artical though for moor insight on the Prophet Noble Drew Ali and everything he brought Google http://www.moorishameericangovernment.land and now you can go to the Supreme teaching of our illustrious Prophet and everything he brought us. See the Moorsh Science temple’s we’re foundated for the teaching of who we were as a people before the time of slavery and that we are those same ones even now ( after slavery ). ” Sort of speak then 1779 to 1865 it was physical yet now its all mental for the pursuit of material gains willfully. Yet In surpassing all that , our Prophet warned his people of the wrath of Allah which is sure to come , all one needs to do to see it is watch and pay close attention to the News. And so the teaching are important yet being what we know is the key to salvation. So to be a people is to have a constitution that governs the whole of the sixty Million of our people and that is the core reason the Prophet our Prophet Noble Drew Ali established Our Government. So when this defacto system fall ours government which is here will have then all its true Citizens who would proclaim there Nationality here there and everywhere. Because no real civilized people wants a So called negro in there mist …

This isn’t the organization founded by The Prophet Noble Drew Ali, and yes his Movement is still in existence of The leadership of The Supreme Grand Sheik E.Braswell Bey, the 8th in the line of succession, these other Moors Praise Allah for there good works aren’t authorized by the Prophets temple to assemble and a lot of the history that you are quoting is wrong you need to get in Contact with The true Moorish Science Temple of America, who has the archives of this National and Divine Movement.

ISLAM Brother, Sister

A Moorish Science Temple is needed where i live thats in Spain Al-Andules.

It’s fascinating to see Moorish Science experiencing a resurgence! It raises interesting questions about identity, spirituality, and cultural history. I’m curious how this revival is affecting communities that engage with its teachings today.