When Esther J. Hamori’s brother died by suicide, she entered into a period of religious exploration, eventually returning to Judaism, the faith tradition she’d grown up in. That in itself is not unusual — many people turn to religion in times of grief — but Hamori, a professor of the Hebrew Bible at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, found consolation in an unlikely place: biblical stories about monsters. In these mythical creatures, Hamori saw a recognition that the world we live in can be sinister and unpredictable. She realized the stories we’ve created about monsters can tell us a lot about ourselves.

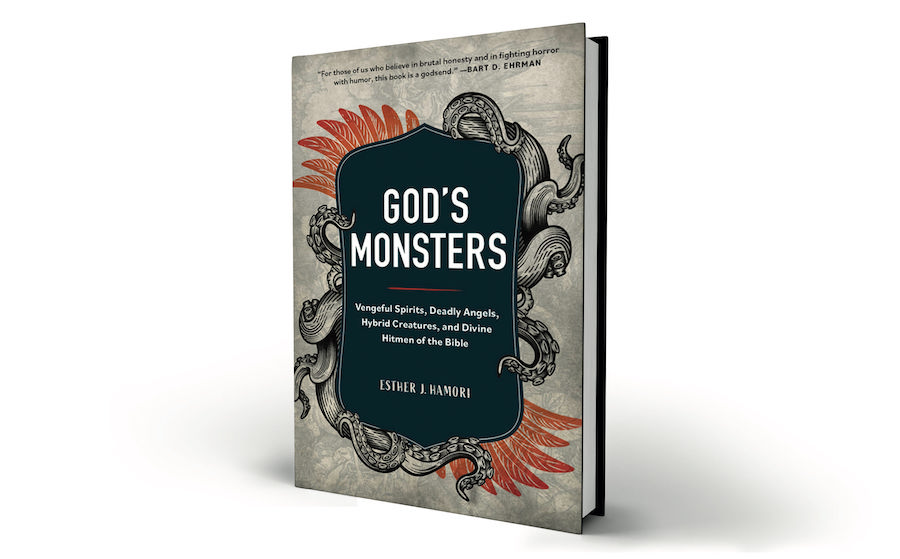

Hamori explores all of this in her latest work, God’s Monsters: Vengeful Spirits, Deadly Angels, Hybrid Creatures, and Divine Hitmen of the Bible. It’s a highly readable book; Hamori’s prose is engaging and funny enough to keep just about anyone’s attention. She’s also an avid consumer of pop culture, sprinkling references to films like Reservoir Dogs and Star Wars throughout her writing. But beneath all the humour and witty asides, Hamori is delving into serious theological questions: What does it mean to be a monster? How do popular ideas about God — in particular, popular Christian ideas about God — differ from what’s actually written in the Bible? And what happens when those things intersect?

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Some of the monsters Hamori writes about are the ones readers might expect: Goliath, the Leviathan, the various demons that populate the Old and New Testaments. But the book also looks at the menacing side of biblical beings that we typically think of as benevolent. Take angels, for example. As Hamori points out, there’s a good reason why the angels in the Nativity story begin every encounter with humans by telling them not to be afraid — mainly because those humans have every right to be terrified. Throughout the Bible, angels have been responsible for many violent acts, like murdering 70,000 Israelites and nearly destroying Jerusalem as a punishment against King David.

More on Broadview:

- ‘Satan Wants You’ revisits the ritual abuse scare of the ’80s and ’90s

- What happens after we die? This compelling exhibit offers answers from cultures around the world

- How apocalyptic scriptures can guide the church in hard times

Deadly angels don’t just exist in the Old Testament, either. The Book of Revelation is full of angels killing and torturing people in horrifying ways. Sure, you could argue that those angels are just following God’s orders, but the point is that they’re a far cry from the sanitized Christian version of angels, those harmless ambassadors of goodwill with their white robes and fluffy wings.

One of the most fascinating chapters in God’s Monsters is about Satan. For Christians, he’s the devil, God’s ultimate foe, the evil force trying to snare human souls for the pits of hell.

But Satan wasn’t always the ultimate bad guy. In fact, Hamori describes his original form as more like a “nondescript heavenly bureaucrat.” When a satan (all lowercase) first appears in the story of Balaam in the Book of Numbers, he’s an angel of the Lord performing a very specific function: in Hebrew, “satan” means “adversary,” and that’s exactly what he is. In the Book of Job, he gains a definite article and becomes the satan (still all lowercase), and though he does torture poor Job, he’s clearly still working for God. It’s not until much later, in the New Testament, that Satan begins to take on the connotations he carries in modern Christian theology.

In less-skilled hands, these arguments might come off as an attempt to debunk the Bible, but Hamori has no interest in anything that facile. Instead, she wants to rescue scripture from what she refers to as “domestication” — the popular tendency to turn this complex set of stories into a black-and-white narrative about a God who always protects and cares for God’s people. The reality of the Bible is much murkier and, by consequence, much, much more interesting.

“The Bible isn’t a solution to the struggles of life, but a reflection of them,” Hamori writes in the final chapter of God’s Monsters. Though the Bible’s authors lived thousands of years ago in a cultural milieu far removed from our own, they were wrestling with many of the same ideas that we still do today. Why do bad things happen? What kind of loving God would allow faithful followers to suffer so much? How do we square God’s violence with God’s goodness?

Reducing the Bible to a simple story of good versus evil doesn’t help us answer those questions. Instead, we have to face the monsters for what they are.

***

Anne Thériault is a journalist in Kingston, Ont.