The path from birth to death is perilous, unpredictable and rife with existential crises. Yet for the span of an hour of two, an exhibition on now at Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) succeeds in making mortality relatively tidy and navigable.

This doesn’t mean “Death: Life’s Greatest Mystery,” which runs until April 7, is for the faint-hearted.” Right away, visitors are greeted with a wall of nerve-racking inquiries they must skim through before making the plunge into the unknown: “Do I have to die?” “How will my death affect others?” “What will happen to my body?” “What will happen to my spirit?”

One of the first pieces looks like something a group of children put together on Bristol board in response to these harrowing questions. It’s an intriguing collage of assorted images, and across its terrain visitors can spot pictures of funerals, skeletons and angels. There’s the Grim Reaper with his signature sickle, Frankenstein’s monster and Dracula, who both cheated death through supernatural means, and Jack sacrificing himself for Rose in Titanic, debatably the world’s most unnecessary fictional death.

The work is deliberately confusing and ambiguous, as the subject of death tends to be. The rest of “Life’s Greatest Mystery” points to some possible answers, or at least some philosophical perspectives to ponder.

As one moves further through the exhibition, death emerges not as an inevitable doom but as a necessary motion in a mechanical cycle. When a whale dies, its carcass feeds an ocean. When a human or an animal dies, it can feed the dirt or the worms. Can is the key word here, because the exhibition also explores other means of handling the dead, like mummification, embalming or cremation. The displays include a stuffed coyote with a curious gaze, and urns for preserving the organs of Egyptian nobility.

More on Broadview:

- Quilting exhibition celebrates Nova Scotia’s Black communities

- Why funerals still matter

- National poetry contest finalist Faith Arkorful talks family ghosts, love and womanhood in debut collection

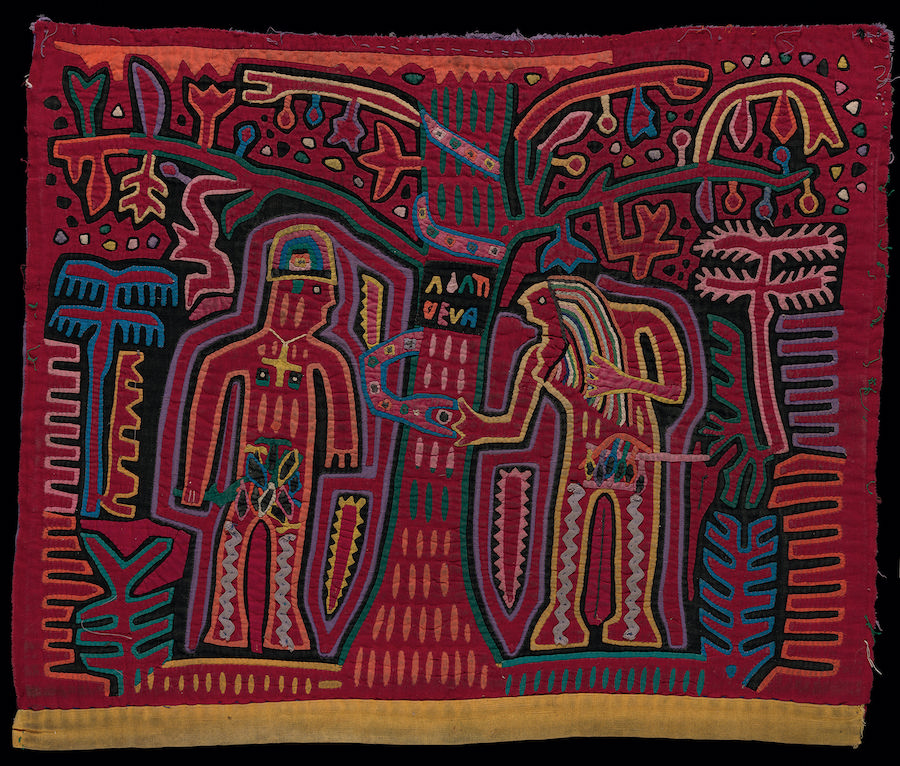

Also featured are lavish offerings for the dead (to appease them in their afterlives so they don’t negatively interfere with the living), Mexican Day of the Dead treasures and, a personal favourite, a magnificent red-and-gold umbrella used in New Orleans funeral processions.

But not everything is safely behind glass. Visitors must brace themselves for the putrid stinks of the decay odours on offer, a rather unexpected interactive activity. You open a flap, lean down, and you get to smell the fragrance of rotting corpse. I tried it. It’s wretched.

For almost every question a person might have about death, there’s a piece in “Life’s Greatest Mystery” that tries to answer it. Is immortality a good idea, for instance? The Ancient Romans thought not; the gods were unbearably annoying when bored and would have been better off with time limits. Does hell exist, and what does it look like? A Chinese tapestry presents it with a domineering, bureaucratic hierarchy that is disturbingly adjacent to real life. Are ghosts real? The Japanese believe you could become a yūrei, or a “dim spirit,” if your death rites are not properly observed. What most cultures, both old and modern, seem to agree on is this: your fate in death often depends on your circumstances and behaviour in life.

The dead deserving proper respect is also a core principle of the exhibition, which is on tour from the Field Museum in Chicago. When the show first opened in Toronto in late October, the ROM proposed altering a display on Palestinian Muslim burial and mourning practices due to sensitivities around the Israel-Hamas war. The changes included cropping an image of a painting to omit a scene of soldiers holding a dead Palestinian, and removing the word “Palestine” from a panel.

Following an 18-hour sit-in by Palestinian American artist Jenin Yaseen and a collaborator, the ROM backed down and agreed not to change or censor any of the content. The original display is presented in full, as it should be.

Want to read more from Broadview? Consider subscribing to one of our newsletters.

Death is everywhere and it is unavoidable, but it is never an end. That is the central, stabilizing theme of the exhibit, normalizing what many consider an uncomfortable, fear-inducing cultural venture. Death, universally, is merely the next step in an ecosystem, a family, a community or a legacy.

Before leaving the exhibit, visitors are invited to write down a memory of someone who has died and post it on the tree of life wall.

Blossoming with colourful sticky notes, the tree is a poignant reminder that our loved ones are always with us, in life and beyond.

***

Emily R. Zarevich is a freelance writer and cultural critic in Burlington, Ont.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s March 2024 issue with the title “Mortality at the Museum.”

Thanks for reading!

Did you know Broadview is the only media organization in Canada dedicated to covering progressive Christian news and views? We are also a registered charity and rely on subscriptions and tax-deductible donations to keep our trustworthy, independent and award-winning journalism alive.

Please help us continue to share stories that open minds, inspire meaningful action and foster a world of compassion. Don’t wait. We can’t do it without you.

Here are some ways you can support us:

Thank you so very much for your generous support! Together, we can make a difference.

Jocelyn Bell, Editor/Publisher, CEO and Trisha Elliott, Executive Director

Comments

Randi Cherry says:

Thank goodness, the esteemed ROM backed down from the "Woke" stance around Palestinian images in the "Death" exhibit!

And thanks to Jenin Yaseen and the collaborator for sitting in on behalf of Israelis and Palestinians and all Life Supporters.

All living forms die. It is to be hoped that true humanity and conflict resolution skills are evolving so that people on both sides of an issue that continues to be "solved" by war will no longer be dying generation after generation and their lands laid waste.

Thank you, ROM, for hosting this magnificent exhibit.