The barren spot near Haliburton, Ont., seemed an unlikely place for redemption. So much gravel had been dug out of open pits here for so long that the land was labelled industrially exhausted.

And yet, on this sunny Saturday morning early last fall, over a dozen volunteers gathered in the graveyard of this vast gravel mine about three hours north of Toronto with boots and shovels and nearly 2,000 trees to see if they could make two small pieces of it — each measuring 10 metres square — come back to life.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Their aim was to pack a total of 10 native trees and shrubs into every last square metre of soil, mimicking the composition of the neighbouring woodland.

These tiny forests are part of an expanding worldwide experiment in urban and suburban forest regeneration developed by the Japanese botanist Akira Miyawaki, who died last July. Miyawaki found that the plants compete so hard for nourishment, water and sunlight that they grow a lot faster than any single tree planted on its own. Rather than needing 200 years to mature, a Miyawaki forest takes just 20.

The fact that the Miyawaki method is igniting imaginations around the world reflects an evolution in thinking about both forests and trees. These plantations are no longer seen primarily as future lumber. Instead, they’re also considered a healing balm for many of the wrongs humans have inflicted on the planet. They can suck up carbon, stabilize watersheds, recharge groundwater, halt flooding and filter pollutants out of the air, not to mention bathe the human soul in tranquility.

The World Economic Forum has launched a movement to plant a trillion trees by 2030, a component of the United Nation-sponsored decade on ecosystem restoration that is now underway. In November, nations from around the world enthusiastically embraced the theme of stopping and reversing deforestation at the climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland. Frankly, trees are hot right now.

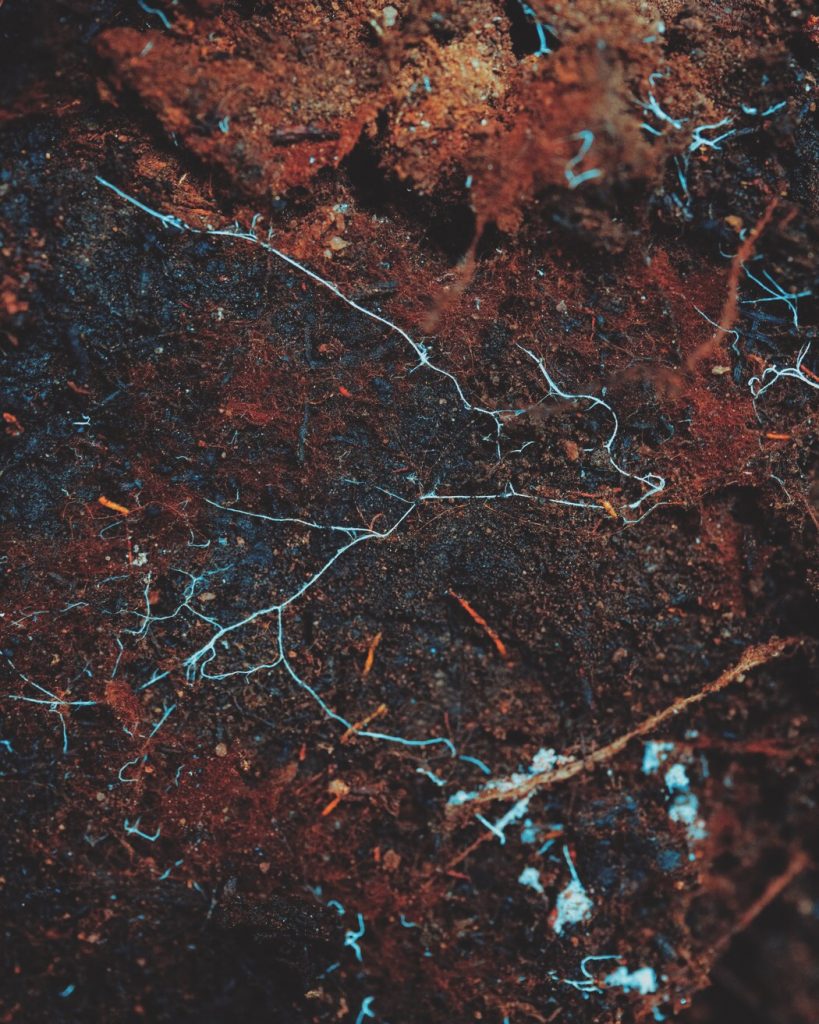

But the reassessment of what forests are for runs deeper than the recent realization that they can help heal the planet. Scientific studies over the past couple of decades have found that forests are intelligent woodland communities. Their members are connected underground by a vast botanical nervous system made up of thready fungal roots called mycorrhiza.

“I call them societies now,” Suzanne Simard told me over Zoom. She is the fabled forest ecology professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver who has spent her career documenting how trees and other forest plants communicate. Her TED Talks on the subject have had more than 10 million views. Her book, Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest, came out last year.

Forests are even more than a community of plants, she told me. They have what she calls “emergent values,” something that in humans could be called a moral structure. She has shown that they value having neighbours, nurturing multiple species and sharing resources among species. Trees have memory. They can learn. They sacrifice their own well-being for that of others. They recognize kin.

“The more we look, the more we understand that interactions start even before germination. There are all these microbes coating seeds, interacting with fungi, that are sending signals back and forth and telling each other, ‘Hey! I’m here!’ so that they know,” she said. “It’s incredible, really.”

I happened on two forests recently that helped me understand just how vastly we’ve transformed how we see trees. One was the tiny Miyawaki project, now known as Abbey Gardens, just planted near Haliburton. The other came to life 65 years ago and lay undisturbed and unremembered until last year. The thread that connects them is my brother-in-law John Patterson, who turns 78 this year.

When John was 12, he was a member of the junior foresters’ club at his high school in Fenelon Falls, Ont. The club was linked to the provincial Department of Lands and Forests, now the Ministry of Natural Resources. Through these high school clubs, the department encouraged the planting of tree seedlings, even distributing them for free. The aim was to develop country forests, an early effort at replacing what had been cut down.

So John got a cardboard box of 250 seedlings from the province: ash, pine, cedar. He got permission to plant them in his favourite place in the world: the farm of his uncle Sherman Northey, near Lakefield, Ont., maybe an hour’s drive from his home in Fenelon Falls. He and his father, Rev. William Patterson, the town’s United Church minister, spent part of a day planting them in razor-sharp rows in a stretch of rough bush at the top of a sloping field. Ash in one row. Pine in another. And so on. A metre between each tree. Two metres between each row. It took father and son four hours.

And then John forgot about all the trees he’d planted. “Why didn’t I go back and visit them?” he asked me recently, incredulous.

For 65 years, he didn’t plant another tree. Like his father, he became a United Church minister. After his first assignment in rural Ontario, he lit out for graduate studies followed by a three-decade stint in Asia and other parts of the world working in community development and ultimately starting a tech company. He’s now a philanthropist based in Haliburton and Toronto.

He founded Abbey Gardens on the exhausted gravel pit. And last summer, having heard about the Miyawaki concept from friends who used the method on a site on the edge of the city Pune in the western Indian state of Maharashtra, he decided to rehabilitate a piece of the gravel pit with his own tiny perfect forest. As he made plans for the Miyawaki forest, the unexpected happened: suddenly, he remembered the forest he’d planted when he was 12.

“Somewhere at the back of my mind was this memory, and it came to the surface,” he said. At once, he planned an expedition with his entire immediate family to rediscover the forest, arriving in high excitement at the farm, now owned by his cousin Bill Northey. But then, mosquitoes.

John caught a glimpse of the forest and was relieved to know that it had survived the decades, but he couldn’t take in its breadth because of the bugs. He pledged to return.

On a brilliantly sunny and warm afternoon in October, I met him at the farm with my husband, Jim, who is John’s youngest brother. It’s a big farm, and John drove the three of us up a laneway that led toward the back fields, pointing, summoning memories.

Here was where he stayed the summer he was eight (when his mother was pregnant with Jim), taking the long train journey from the family home in Quebec with his sister, Barb, who was 10. Here was where he worked as the hired help every summer from the time he was 12 until he was 18, driving the tractor, working the fields, being taken seriously despite his young age. He loved it. “I was dealt with as a human being. I wanted to do something that had some substance,” he recalled.

We made the final part of his sylvan quest by foot, tramping over empty fields that had been filled with soybeans until the harvest, stopping to savour the landscape. And then, like walking through a magic archway into a secret land, we entered the forest. John was entranced. “These are our trees. These are definitely our trees,” he said as he wandered through the rows, touching the rough trunks, breathing in their scent. “Look at that. That’s beautiful.”

They weren’t fat trees. Many were spindly. Some had fallen. Many had spawned offspring. The rows were still tightly defined. “How many trees do we need to plant to restore the health of the Earth? But we got started on it 65 years ago,” he said as he peered up at their crowns. “Every day it grows a little bit more and eats a little bit more carbon out of the atmosphere. It’s doing what the Earth needs. You could bury me here, and I’d be as happy as a lark.”

As inspiring as John’s grove is to him, it is also representative of how we used to think about trees. At one time, the ideal was to plant them far apart in orderly rows, the better to cut them down later. We planted them in our own utilitarian image, Simard told me. “It’s handy if they’re in rows.”

Trees were deliberately planted apart from each other to avoid competition between them. That fit into the old idea that trees don’t have communal relationships and will do better if they can easily get their own piece of the pie.

Simard’s research has blown that idea out of the water. Trees do compete, but they also need other types of interactions to help them thrive. That’s what seems to be happening in the Miyawaki forests. While Simard has not studied Miyawaki plantings, she has conducted laboratory experiments to examine what happens when you pack plants tightly in a small pot with and without fungal threads. The plants’ proximity to each other means that they start to interact right away so you don’t have to wait decades to see what’s going on. It’s like time-lapse photography. “You can speed up time by having them so packed together,” she said.

In her potted experiments, Simard found that the plants grew out evenly when the trees were linked by the mycorrhizal threads, while those without the fungi grew at different rates. She interpreted that to mean that they shared resources, the bigger plants supporting those that were younger and smaller.

But she pointed to a study by David Janos of the University of Miami showing that the presence of mycorrhizas accentuated height variations among the plants. Despite their different outcomes, the two studies showed a similar phenomenon: that underground fungal networks affected how the plants grew. “The important thing is that soil biology made a difference in how the forest was structured, so they’re working together,” she said.

While that knowledge has a long history among many Indigenous peoples, modern science only began to investigate it in the 1970s and ’80s as people started to move plants around the world, Simard explained. Douglas fir trees sent from North America to New Zealand at that time would simply die. Once exporters began sending soil fungi with the trees, the trees did well.

Simard wanted to know a lot more about how that worked. So, starting in the early 1990s, she ran some experiments in a wild forest in British Columbia. By using two different isotopes of carbon — one stable and one radioactive — she proved that seedlings of different species growing in the forest passed carbon back and forth through underground mycorrhizal networks. It means that trees are not stand-alone. They are physically part of a community that shares the stuff of life. The breakout paper on her findings came out in 1997 in Nature.

To Simard, the implications for managing forests were plain. You have to take into account the soil as well as what she eventually came to call the big old “mother trees” that nurture the whole forest. Instead, there was a backlash from scientists who thought she was trashing the idea that only the fittest survive. They accused her of going against the teachings of evolutionary theorist Charles Darwin. It was like kicking the Pope.

“When it came out in 1997, people said, ‘Oh, that’s cute, but we’re not going to change anything’,” she said.

Today, Simard’s findings that trees collaborate and have wisdom have taken hold in biology textbooks — and in popular culture. Her work underpins the depiction of the Tree of Souls in James Cameron’s Oscar-winning 2009 science-fiction film Avatar and influenced Richard Powers’ 2018 novel The Overstory, which won the Pulitzer Prize. “It’s making its way into the public psyche,” she said.

It doesn’t seem to be having a widespread effect on forestry practices, though. “It has become common knowledge but has not actually translated into how we practise resource management,” Simard said.

Two weeks before we chatted, Simard was protesting against the logging of old-growth forests at Fairy Creek on Vancouver Island. One cedar tree she tried to protect was so ancient and so vast that she crawled right inside it, into a bear den large enough to hold five adults. In vain. The tree was cut down, and the community it once nurtured will be converted into an old-style plantation.

One counterpoint to both the loss of forests and the industrial plantations is the spread of Miyawaki plantings — although, like the forests, the movement is small. A group in the Netherlands has planted more than 100 Miyawaki forests, each adopted by a local school for use as an outdoor classroom. The Indian group Afforestt, whose founder Shubhendu Sharma studied with Miyawaki, has created 138 in 44 cities across 10 countries, planting nearly half a million trees at last count. Other members of the global network hail from Curaçao, the United Kingdom, Pakistan and Germany.

In Canada, the organization CanPlant is beginning to track Miyawaki forests and the native plants within them in a database kickstarted by a grant from the Landscape Architecture Canada Foundation. CanPlant is managed by the ecological consultancy Dougan & Associates, based in Guelph, Ont.

The CanPlant database, which is still being developed, has records of eight Miyawaki forests so far in Ontario and Quebec, said Heather Schibli, a landscape architect with Dougan & Associates. But she is aware of plans for at least 10 more in other parts of the country, including British Columbia and Prince Edward Island and one on Sussex Drive in Ottawa.

“It has the possibility of shifting the paradigms in terms of how people see trees and how they plant them.”

landscape architect Heather Schibli

Among those interested in planting them are representatives from federal, provincial and municipal governments, as well as individuals and community groups, she said. Some of the inspiration has come from Simard’s work, and from the American botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of Braiding Sweetgrass. The dangers of climate heating are spurring interest, too. “A lot of Canadians have contacted us about Miyawaki forests,” Schibli said. “I think it’s part of this larger zeitgeist with climate change.”

One downside of the Miyawaki forest is that it’s expensive because it takes so many plants. And plentiful native plants can be hard to find at a nursery. Ideally, Schibli would advise collecting local seeds so the genetic makeup of the new forest would closely resemble that of the plants nearby. Even so, she said the Miyawaki trend holds great potential to become a new go-to form of planting around homes, schools and corporate grounds. It’s a repeal of the idea of trees as majestic, lonely sentinels.

“It has the possibility of shifting the paradigms in terms of how people see trees and how they plant them, shifting from an individual park tree to planning a community and being okay with trees growing closely together,” she said.

In fact, Schibli, a self-confessed “tree dork,” has planted a Miyawaki forest in her own backyard. Her tiny forest, which measures eight metres by nine metres, contains 230 native woody plants replacing grass and hedges. Among the new plants: sugar maple, black maple, ash, basswood, three types of elm, three species of oak, bitternut hickory and shagbark hickory, hawthorn, serviceberries, a few trembling aspens, some black cherry. It’s a mashup.

“I’m hoping that Canadians, and people beyond Canada, start to think a bit more like ecologists,” she said, adding, “It gives me hope as a mother that we’re reconnecting to other people and also to other species and to the landscape, and that it will bring about more nurturing and a sense of place and belonging and love.”

Preparing the soil is key. Schibli recommends adding compost, mulch, leaf litter and a scant teaspoon of precious forest soil with its all-important mycorrhizas over the whole Miyawaki plot.

In preparation for the September planting at Abbey Gardens, the team added horse manure, spent organics from a brewery on the property, wood chips, biochar (a form of charcoal made from burning plants at high temperatures without oxygen) and wood ash.

One of the two Miyawaki forests on site is part of an experiment being conducted by Edward Smith, a master of biogeochemistry student at Trent University in Peterborough, Ont. When I talked to him on planting day, he told me he had seeded half his Miyawaki plot with buckets of mycorrhiza-infused soil from the forest on the edge of the former gravel pit to see whether that makes a difference.

Like me, he marvelled at how this project diverged from the way tree plantations used to be conducted. “Fungal and bacterial communication in soil is very new research,” he said, looking at the 1,000 trees and shrubs to be planted on his site that morning. “Now, people are really taking a look at answering the unknowns.”

Smith was there with half a dozen or so members of Trent’s society of ecological restoration for the day’s work. They set to it. The site had already been measured up and divided into 100 square metres by green string and stakes. Into each square was destined to go 10 trees and shrubs, including balsam fir, paper birch, red maple, sugar maple, leatherwood, black cherry, chokecherry and fly honeysuckle.

“It’s a marathon,” Smith said. Over the next couple of hours, the saplings went into the ground. A huge collection of empty, muddy black and orange plastic pots piled up in their place.

John Patterson oversaw the whole process sitting in the shade off to one side of the site. He was thinking about the other forest, he told me, the one he created with his father that long-ago day, brought to life by the excitement of a 12-year-old for trees.

In front of him were two nephews, a niece, two of his brothers, his wife, Thea, his son and a few friends, all crowded into the tiny space, packing as many plants as possible into the ground. It was a whole community of kin, collaborating, interacting, waiting for regeneration. Kind of like a forest. He was grinning.

***

This story first appeared in Broadview‘s March 2022 issue with the title “Tiny perfect forests.”

Alanna Mitchell is a journalist, author and playwright. She lives in Toronto.

Fantastic. Everything I’ve ever thought about trees. I just wish I was 50yrs younger.