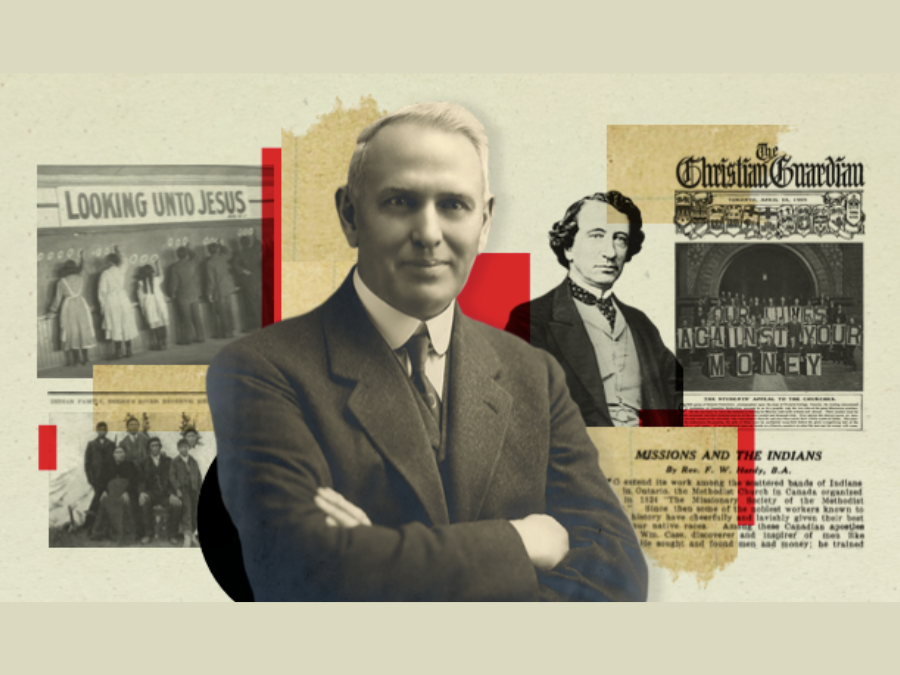

In 1909, Rev. F.W. Hardy wrote an article for The Christian Guardian entitled, “Missions and the Indians,” offering a rare glimpse into the changes occurring in the church’s work with Indigenous Peoples at that time. His article heaps praise on the missionaries themselves while also offering one of the first hints in the publication that the “Indian missions” weren’t going so well.

We don’t know much about Hardy. The Christian Guardian records that in 1908 he was a minister in northern British Columbia, in the Waterways Mission of the Methodist Church of Canada. With a bachelor of arts degree in hand, he was already well educated, but the paper reports that he was preparing to return to college for further study. In 1910, a Guardian notice says he is living in Toronto and celebrating the birth of a daughter.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

It’s possible that in 1909, the new editor of The Christian Guardian, William Black Creighton, received word that this bright young man was coming east from the far northwest. Always eager for stories about Canada’s frontier, Creighton was perhaps aware that his paper hadn’t printed much on “Indian missions” lately. Did it occur to him that a short contribution from the articulate Hardy, experienced as he likely was with Indigenous communities, would help fill the vacuum? This, anyway, is how I imagine that Hardy’s article came to be written.

As Broadview continues its exploration of its historic relationship with Indigenous communities, the period of the early 1900s reveals how the quality and number of articles on Indigenous issues continued to decline in The Christian Guardian, Broadview’s predecessor publication.

Three things happened in the early 20th century that significantly influenced The Christian Guardian’s coverage of Indigenous Peoples. First, the rise of residential schools, which accompanied the settlement of the Prairies. Second, the Methodist missions’ shift away from a focus on individual conversion to a social gospel approach to Christianizing society. And third, surging enthusiasm for overseas missions.

Hardy’s lonely article attempts to explain changing attitudes toward “Indian missions” and offers a brief insight into the challenges of Methodist leadership at the time. But before we dive into Hardy’s writing, let’s revisit the cultural forces that gave rise to it.

***

Since the time of Confederation and the passing of the Indian Act in 1876, Canada’s notorious reserve system had been busily and effectively clearing Indigenous people off the land. This was done in large part to make farmland available to settlers.

In 1883, Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald called for three new residential schools to be constructed on the Prairies. Drawing on the model of the first schools begun in Ontario decades earlier, this moment marked the start of a residential school building spree in the West that would continue for decades more. By 1909, at the time of Hardy’s writing, churches were running (with federal government funding support) 74 residential schools with a combined enrolment of 3,841 students.

Moving Indigenous adults onto reserves and children into schools was more than a physical removal. It also removed stories and erased history. “The government was selling the West to settlers,” explains Cheryl Troupe, professor of history at the University of Saskatchewan, a Métis and member of the Gabriel Dumont Local #11 in Saskatoon. “They were selling this idea that it was a peaceful place, empty, a Garden of Eden with no prior history to complicate things.”

More on Broadview:

The Methodist Church was certainly motivated by a vision of the Garden of Eden. Its leadership sought to make Canadians worthy of this biblical utopia. At one time, they had believed the best means to do this was through conversion to Christianity and fervent commitment to a life of prayer and worship.

But the ethos of missions was changing. Where revival meetings had once been a focus, the era of the social gospel brought something new. As the largest Protestant denomination in Canada, the Methodist Church felt a special burden of responsibility to mould the character and culture of the new country. Schools and social engineering, they now felt, were better vehicles to steer society toward God’s intended ends than conversion and prayer alone.

These aspirations were not only national; they were global. At the turn of the 20th century, as the British Empire reached its zenith, opportunities for missionaries to travel to far-flung lands exploded. Canada’s Protestants were among the most enthusiastic participants in this movement. By the mid-20th century, Canada had more missionaries abroad and its churches were investing more money in this enterprise per capita than any other country in the world. “At this point, a kind of a mission hierarchy develops,” says Rev.

Sandra Beardsall, professor emeritus of church history at St. Andrew’s College in Saskatoon. “The most prestigious is of course overseas, and especially China, Japan and a little later, Korea.” Indigenous missions largely fell off people’s radar.

Creighton, editor of The Christian Guardian from 1906, was well known for his national, social gospel and missionary commitments. In his mid-40s, and born in Dorchester, Ont., just a few years before Confederation, Creighton was steeped in the culture and values of his day. As a result, Guardian coverage of Indigenous people and their issues in Canada received far less space and was often tragically complicit in historical injustices.

For example, a story in the Sept. 29, 1909, issue cheered news that the vote had been extended to some of the Indigenous people of Alberta and Saskatchewan. “In future an Indian of these provinces who desires a white man’s right of voting may qualify for the privilege by cultivating and securing the deed of a parcel of land,” it happily reported.

But the story’s author and editors failed to grasp that to take a parcel of land off the reserve would effectively sever an Indigenous family from their community and their identity. The result of such a move would be enfranchisement but also assimilation and the loss of culture.

Another article tells of the building of a new church on the Rama First Nation in Ontario. The Indigenous community had shown its commitment to the project by providing $1,000 for construction — which the story offers as evidence of their Christianization and counts it as a Methodist mission success. But Troupe says the real story is likely more complicated.

“The church is in fact very important to Indigenous people at this time,” says Troupe, noting that beyond the faith itself, the church was an important channel of communication between Indigenous people and the Canadian government. “But we have to remember that even if they were devoutly Christian, it doesn’t mean that they pushed aside anything that was Indigenous,” she says. “There was a real syncretism of religious practice or spiritual practice that still continues today, that ability to bring it together, to evolve, go underground but persist.” This part of the story did not make it into the Guardian.

Far from telling the story of the resilience of Indigenous culture, the paper instead promoted the displacement and erasure of Indigenous Peoples and their ways of life. It announced the rules for how settlers could claim land on the Prairies. And of residential schools, it claimed that many of the students would “undoubtedly live a deeper, fuller life” due to the schools’ influence. It also published advertisements seeking residential school teachers and nurses.

Into this space and time, we find Hardy’s April 28, 1909, article, a prime example of the settler church perspective — and the only perspective published at this time on the topic of Indigenous Peoples and the church’s missions to them. His article begins: “Some of the noblest workers known to mission history have cheerfully and lavishly given their best days to our native races.” The hyperbolic praise speaks to the contemporary enthusiasm for the missionary enterprise.

When Hardy reflects on the past, he casually erases Indigenous Peoples from their place in Canada. He fails to mention, for example, the Indigenous Christian leadership that was so prominent in the first decades of The Christian Guardian. He claims that the earliest missionary work had resulted in “whole tribes” being converted from “barbarism and superstition,” a shameless exaggeration and a blind mischaracterization of Indigenous culture and its persistence.

Hardy underscores for his readers that the approach to missions had changed: “The axe and spade of evangelism [had given] way to the plough and seed-drill of education.” Seemingly unaware of the damage inflicted on children and their families by residential schools, he claims that if anyone had suffered as a result of “Indian missions,” it was the missionaries themselves. Hardy complains that work with Indigenous people had started to feel like a “burden too heavy to bear” and a “daily plod, lacking all pioneer novelty, [where] the returns seemed meagre, and the wheels turned slowly.” Knowing what we know now about conditions in residential schools, we can guess that there were other reasons for bleak feelings within these missions.

The Christian Guardian’s blindness and insensitivity to the injustices facing Indigenous Peoples within Canada would continue through the turn of the century and beyond 1925, the year The United Church of Canada was formed and The Christian Guardian changed its name to The New Outlook. Through the decades, a sense of malaise with “Indian missions” would continue to grow. With Hardy’s article, we see some of the historical factors contributing to that blindness. Perhaps for the first time, however, we also see signs of disillusionment borne of the failure of “Indian missions.”

***

Rev. David Kim-Cragg is a historian, author and minister at St. Matthew’s United in Richmond Hill, Ont.

Vanessa Kennedy, who served as a sensitivity reader for this article, is an Indigenous consultant in Hillsdale, Ont.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s July/August 2025 issue with the title “‘Indian Missions’ Malaise.”

Another excellent piece – thank you. And the Anniversary Issue was outstanding. Congrats!

Is there a link to the actual article by Rev. Hardy in the Christian Guardian?

Hi Julianne,

I have now linked it in the story. It is also here: https://catalogue.unitedchurcharchives.ca/uploads/r/united-church-of-canada-archives/4/6/1/461c6c70a2a3654e54f77cf46d2777bf46a9ce399fda38fed65f31cb8dc1623b/The_Christian_Guardian_1909_04_28_Vol_LXXX_No_17.pdf