Editor’s note: Joe Clark seemingly came out of nowhere to win the leadership of the Progressive Conservative Party in 1976. Canadians were still asking “Joe Who?” when Observer editor Rev. A.C. Forrest sat down with Clark for this interview, published in April 1977. But he became the youngest prime minister in Canadian history when he defeated Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals to form a minority government in 1979. Just nine months later, Clark’s government fell on a budget vote, and in the ensuing election, Trudeau and the Liberals returned to power. Still, Clark went on to serve as secretary of state for external affairs in the government of Brian Mulroney.

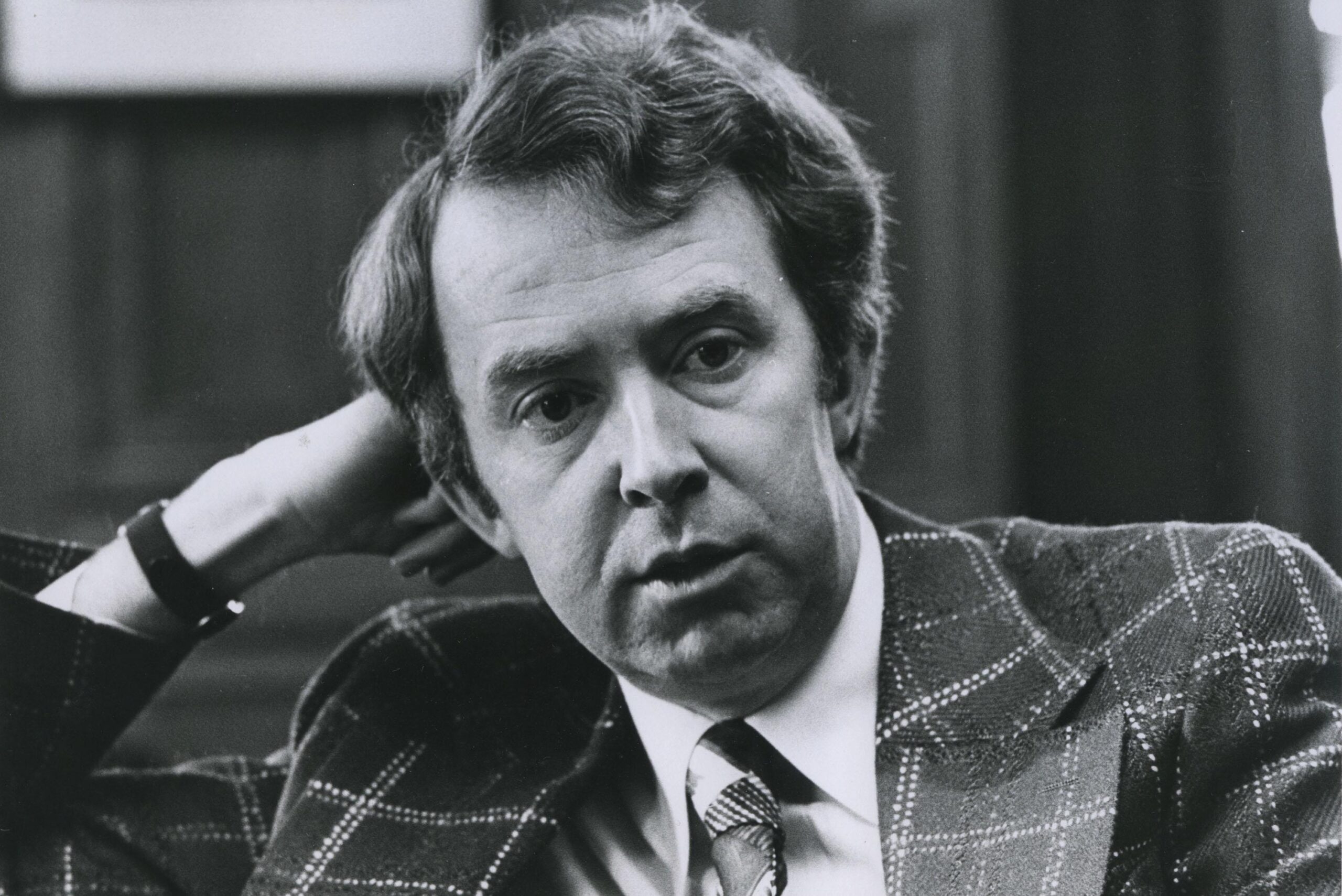

If you believe public opinion polls, P.C. leader Joe Clark will be Canada’s next prime minister. My first reaction on meeting him was to glance at his feet to see if he wore lifts. He is tall, almost six foot, slim and trim. Television had communicated to me an image of a stocky and rather stuffy little man. Well, he isn’t. He’s the kind of person I felt comfortable with – friendly, quick to grin, relaxed. And in the office he seems easy with his staff.

Joe Clark’s words pour out, not always in answer to questions I had asked. He is not evasive, but elusive. Circumlocutive, I think you call it.

Readers may come to their own conclusions, but I wondered why anyone ever thought Joe Clark was a red Tory. It must have been because he was an executive assistant to Robert Stanfield. Or that he voted for abolition of capital punishment.

On international affairs, about which he doesn’t seem well informed? Predictable, right wing, not too interested.

However, he has moved David MacDonald up to the front bench; and MacDonald on world affairs sounds like the best informed, enlightened and travelled in the P.C. caucus.

That front bench, the Ottawa insiders say, tells a lot about Joe Clark. First, that he’s tough, and had the nerve to seat privy councillors in the second row to make room for his new boys. And second, that he’s smart. Those who ran against him are there, from Jack Horner to Flora MacDonald, plus some of the ablest such as Gordon Fairweather.

I kept remembering that Joe Clark has been very successful as a politician. He is given credit for engineering the massive Conservative victory in Alberta. He went after a tough constituency nomination when he might have had an easier one – or so Albertans tell me – won it, and then won the seat in the House of Commons.

A year ago he came from political nowhere to the party leadership. Loyal opposition in the House of Commons, where Joe Clark is said to be no match for Pierre Elliott Trudeau, comes second; winning the next election comes first.

It had interested me that during the last year, so much was made of the religion of Jimmy Carter, who was not long ago Jimmy Who, while nothing was made of the religious faith or lack of it of P.C. candidates.

I found that even in High River friends weren’t sure what religion Joe Clark was – if any. Mr. Clark didn’t tell me much about his religious conviction, but probably he told or implied most of what there is to tell.

The most striking impression among many, for me, was Mr. Clark’s supreme confidence. He doesn’t say, “If I win…” He apparently has no doubts, or if he has he isn’t going to let them show. The young staff in his office exudes the excitement and confidence of a winner, as the P.C. offices did in the early Diefenbaker years. And they call Clark “the Leader”.

In the ten months after your election as leader, you spent 158 Days away from Ottawa and the House of Commons, politicking on the hustings. Why?

That’s where you win elections, and my principal to right now is to win the next election.

I have a responsibility to ensure the Opposition performs its function, and I think we are doing that. But I was not elected to propose; I was elected to try to form a government, and my judgement is that you do it in the country.

It is important to note that I am not the only one who is travelling. I have most of my senior colleagues on the road. I have to put together a cabinet that can reflect the whole of the country, that knows something about it, and there is no substitute for going out and seeing things.

You are saying that your priorities are now, one, to win the next election, and two, to have people who are prepared to be good cabinet ministers?

Yes.

‘In the ‘60s, we had an unusual faith in the capacity of national government to solve local problems.’

In the United States, President Carter has promised to do something about the quality of American life. Could your government do anything about the quality of Canadian life?

In the ‘60s, we had an unusual faith in the capacity of national government to solve local problems. In many cases, the evidence is in that it didn’t work. We lost an understanding of the capacity of local communities to solve local problems. If we can reinforce the capacity of communities to do things for the people who are part of them, it will have an impact on the “quality of life”.

When I was growing up in High River, for example, the hockey coaches tended to be neighborhood fathers. Today they are recreation directors. I think we pay some price for that bureaucratization of what had been private functions.

I think we may have overlooked an asset in our concentration on trying to develop some kind of sea-to-sea national identity. Probably the nature of Canada resides more in a series of regional identities, or local identities. And that is strongly related to a sense of community.

I would be very interested in practical suggestions as to what governments can do to develop the sense of community – perhaps even vacating some of the things they do now.

You have gained some Brownie points, and lost some, because your wife has retained her maiden name. What is your thinking on this?

I don’t think many people really object to Maureen’s using her maiden name. What concerns them is that it symbolizes changes whose consequences make them uneasy. That’s why it’s an issue.

We did not make that decision for political reasons and we do not pursue it for political reasons. But there are some political consequences from it. I am a politician, and you take advantage of your assets as you can.

I think clearly one of my assets is, as leader of my party, that my wife is known to value her own identity and I am known not to be bothered by it.

I understand you are Roman Catholic. Are you a practicing Catholic?

Yes, we are practising Catholics. I feel comfortable at church. It might have more to do with a sense of continuity than anything more inspirational.

I try to practise my faith. I try to be charitable towards people, which I think is an operating Christian virtue, and I try not to parade my Catholicism.

High River, I gather, was ecumenical before the word was known. How great an influence for good was the church in that small community?

It was ecumenical in its early days – and that’s not so long ago, because they could only afford to build one church. Later lines hardened, and my father was made conscious of being Catholic. He was in the minority, and there was a lively sense of being “different”. That has changed now.

The churches were active I think principally as social centres, in that they were one place in which people from a variety of backgrounds came together.

The church tends to go to the government with its concerns, such as immigration and world hunger. Do you have any feeling about the church as a political lobby, or should it change opinion through its own congregations?

I think Christian churches have an obligation to make Christianity work. My concern about church lobbying (if I had one – which isn’t often) is whether sometimes the spokesmen for various denominations are representing with any degree of accuracy the feeling in their church.

To the degree that church leaders do express a consensus, I think their perspective should be heeded unusually. Church groups by their nature spend more of their time on ethical questions than most people do, and there should probably be more attention given to their point of view – provided it’s representative. That’s the caveat.

A church can do three things. It can send a delegation to wait on a minister or the prime minister. It can work through the members in constituencies. Or it can make public utterances which it hopes will influence public opinion.

I think an ecumenical representation is going to be most effective. And nothing will be effective unless there is some demonstration of its representative nature.

‘In the west there has been a decline in concern about language problems and a deeper concern about the country.’

It would seem to many English Canadians that a French-speaking prime minister from Quebec, sympathetic to its aspirations but committed to Confederation, would be the best position to deal with the separatist question. How would you see that?

The problem in Confederation are not simply Quebec related. They relate to other regions in the country. I suppose that what is important to Quebeckers, who are anxious to assess their capacity to live in the country, is not that a French-Canadian leader is responsive to their concerns, but that someone who can have a larger claim to representing English Canada is responsive to their concerns.

Part of the reason the Levesque government has such influence now in Quebec, among people who are far from being committed to the partition of the country, is that they are seen as a new generation of leaders. We have an opportunity to compete with that. If we can attract candidates of quality in Quebec, these new Conservative members of Parliament, or cabinet ministers, can compete effectively against the Levesque wave because they will be a fresher federalist wave. I take it as one of my major responsibilities to recruit candidates of standing in Quebec.

What reaction to the Quebec election have you found in western Canada?

In the west there has been a decline in concern about language problems and a deeper concern about the country. My hope is to encourage Canadians to see that we have an opportunity to review national arrangements maintaining the integrity of the nation, but reviewing them in a way that will be of benefit to that region.

One member of your caucus, on the front bench, seems to have said that as a last resort the government might have to use force to keep Quebec in Confederation. Do you see any situation in which a Conservative government would do that?

I don’t think sending the army in would stop a province or a people who are determined to separate. I wouldn’t say I would never resort to force, but it would be very unlikely that force would be effective. If we get to that, we have pretty well lost the game.

‘Until there is some system that can guarantee there will not be an abuse of a product of a Canadian government agency . . . we should not be involved in implanting them in sensitive situations.’

I’d like to ask you about some areas of policy in which the United Church has concerns and some stated positions. First, about immigration. One member of your caucus thinks we should do more, especially about refugees. Others feel we have gone too fast in admitting too many what is your policy?

Our position would be that we should begin to hold down immigration until we have been able to overcome some of our economic stagnation.

The church has tried to pressure government on trade policies with South Africa because we dislike apartheid. Do you think government should use economic pressures against such countries as South Africa?

Not in relation to apartheid. I think it is possible to attempt to employ sanctions when questions of legality are involved, as in Namibia. When it is a question of approval or disapproval of policies, you get on very risky ground, even in relation to as serious a problem as apartheid.

What about the sale of Candu reactors to South Korea?

We oppose it. There’s a distinction here. Sanctions stop non-crown operations from doing things they would normally do. The sale of Candu reactors involves the Crown. Until there is some system that can guarantee there will not be an abuse of a product of a Canadian government agency – in other words, that they would not be used directly or indirectly for the production of weapons – we should not be involved in implanting them in sensitive situations.

Poverty is a “quality of life” issue. What is your policy on that?

I would be inclined towards specific programs to help specific problems, rather than engage in national programs designed to elevate national standards.

How can a Catholic who has a prominent place in the political life of Canada be happy with our present situation on abortion?

First of all, I cannot be a spokesperson from my church on that question. Personally, I oppose abortion on demand because I think it leads to a sense of social irresponsibility. But I would amend the present law because it is very difficult to enforce. Some hospitals simply do not allow abortions, and that in my judgement imposes a special hardship on the poor. The well-off person who is refused an abortion in Chicoutimi can fly to New York for one. I would like to have the law operate nationally.

What about lotteries?

I think a prohibition of lotteries would be ineffective, just as prohibition of beverage alcohol was. I don’t think that state can effectively stop that kind of activity.

A tougher question is whether the government of Canada should be actively promoting it. I suppose I come down on the lottery side by saying there remains an option not to get involved. I don’t think Loto Canada is going to appreciably affect public morality in Canada.

‘I think we are involved in a contest – of values more than ideologies.’

You were critical of Mr. Trudeau for going to Cuba. Do you really support the American policy to isolate Cuba?

I was specifically critical of Mr. Trudeau for going to Cuba at a time when Cuba was in Angola. It would have been prudent to recognize that would invite unnecessary concern in the United States.

I would increase trade with Cuba if they have things that we need. I would not make a point of trading with Cuba ahead of other sugar producers, but neither would I make a point of not doing it.

You appear to some people to be a real old-fashioned Tory on international issues.

I have some views that I suppose could be called traditional. I certainly support active participation in NATO, because I think we are involved in a contest – of values more than ideologies – that is at stake. We are not neutral there.

In regard to the United States, I think that, putting aside all the American excesses, and the fact that they naturally are going to pursue national interests that conflict with our national interests, they are a friendly country. My approach would be dictated by that.

I don’t want to imply that my international focus is limited to NATO and Washington. One of the areas in which I am trying to broaden my own understanding is in Canada’s relation to the Third World. Two of our members in particular, David MacDonald and Doug Roche, are very concerned about that. I am not yet ready to take a final personal position on Third World relations. But I certainly can see that case that Doug particularly and David make to me about the importance of response y countries like Canada.

This story originally appeared in the April 2017 issue of The Observer with the title “Here’s who Joe Clark really is.”