Dear Dad,

I can imagine you, in your early 20s, still a few years away from family responsibilities, driving home late from a night out drinking with the boys. You’re on a concession road in southern Ontario. It’s fall, and you’re a bit buzzed. You reach under your seat for a cassette tape and take your eyes off the road for an instant, missing a stop sign (in later versions of this story, you’ll say it had been pulled down as a prank — the world always stacked against you).

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Your truck crashes into a tree that will bear the scars of the impact for decades, sending you headfirst through the windshield. It takes hours before someone finds you lying in the cold. You come away from the accident alive but with a shattered pelvis, a broken hip and various contusions and lacerations.

To manage your pain, your doctor prescribes opioids, a common medication given during post-surgery recovery in the late 1980s (and to this day). You’re off work after the crash, living on disability benefits from your blue-collar union job, with nothing to do for years but heal.

I imagine this is when the seeds of your addiction are planted. Maybe you take a little more than the doctor prescribes to while away the hours. Maybe you’re in enough persistent pain that you need the relief the opioids offer. Whatever the case, you keep taking the pills, and the doctor keeps prescribing them. You’re under medical supervision; what could be wrong?

You’re still a young man, arguably in your prime. I imagine it must grow increasingly frustrating for your life to be on hold while the world keeps spinning. You’re also an extrovert. You gain energy and joy from being around other people. For a few years, you’re able to maintain a fairly regular life. You continue to mix with some of the same buddies you’ve hung out with since high school, regularly pumping alcohol and pot into a body pulsating with chemicals. During the physical rehabilitation and unending discomfort, like a mosquito hovering around your ear that you just can’t swat away, the one bright spot is your social calendar.

The people around town who know you for your easygoing and chatty nature probably don’t notice any difference in your personality when they see you out on the street or at the local coffee shop. Your parents and friends don’t have any reason to be concerned either — you’re still the life of any party and a sought-after guest at local gatherings.

It’s at one such occasion in the early 1990s that you run into my mother. You had known each other in high school, and she is even more attractive now. During your teenage years, she just saw you as an irritating kid forever pestering her for hugs. You’re taller and stronger than you used to be, but I don’t imagine it’s your looks that catch her attention.

You are, at your core, an earnest man with a generous heart. You’re not only easy to talk to but, at this point in your life, you’re understanding and non-judgmental. When my mother reveals she’s a struggling single parent to a two-year-old daughter — me — it doesn’t deter your pursuit of her. In fact, you welcome us both, wholeheartedly, into your life. You bring us to Sunday dinner at your parents’ house and get to know me and my Barbies at the little townhouse my mother and I share. As the relationship grows more serious, you even offer to legally adopt me because my biological father is not in the picture (an offer my mother declines).

Since I’m only a toddler when we first meet, I don’t have a clear picture of the setting or circumstances, but I do remember the distrust I feel toward you. I expect the bulk of this comes simply from a child’s jealousy over having to share her mother’s time with someone else. But, even as I grow used to you and get so comfortable with your parents that I refer to them as Grandma and Grandpa, I have a sense of unease whenever you’re around. But I’m too young to sort out my emotions — besides, there’s no time.

You and my mom are in the type of whirlwind romance that only seems to happen when we’re in our 20s. After less than a year of dating, my mother finds out she’s pregnant, and the two of you decide to get married just ahead of my third birthday. Practically overnight you go from an injured but carefree young bachelor collecting disability benefits to a fiancé responsible for what will soon be the lives of two very small children, one of whom is increasingly wary of you.

In 1993, you’re 28 when you marry my mother and my brother is born. I’m 28 now, unmarried and childless, and can empathize with the emotions that might have been raging in your heart: uncertainty, anxiety and fear. I can imagine the pressure you feel after the wedding.

Unfortunately, your pain and addiction don’t subside with your new family.

By the mid-1990s, you’re still off work and in a lot of pain, so you’re sent to a pain management clinic in the city. A doctor switches you from Percocet, an opioid that lasts up to five hours, to a trendy new drug, hailed as a medical breakthrough, called OxyContin. This controlled-release opioid has up to 16 times the amount of oxycodone that your Percs contained and lasts for up to 12 hours. You go from being high for a few hours at a time to being high all the time.

After a year of us all living together, my reservations toward you become justified. At four, I’m a wilful little girl, constantly testing the limits of those around me. Since Mom works full-time to help support us (your disability benefits don’t quite stretch far enough), you’re in charge of daytime care for me and my brother. As a result, you are often the target of my stubborn nature.

One afternoon, I’m engaged in my favourite disgusting childhood habit: nose picking. You’re watching television with my brother in the living room when you notice and tell me to stop. Always one to finish what I start, I move into the kitchen to continue my booger mining.

“You better not be picking your nose in there,” you yell. Your tone is harsh, angry. Not the jovial one I’m accustomed to. You walk into the kitchen and catch me in the act. There’s something wild and animal about your eyes. Your tobacco-stained teeth are bared as you start swearing at me. My tiny heart pounding wildly in my chest, I run toward the stairs.

Your footsteps thunder behind me as I will my little legs to go faster, burning with each step. Hot tears are running down my face. You’re screaming and swearing as I rush into my bedroom, slam the door and push my entire body weight against it. The strength of a four-year-old is no match for you, though, and you hurl the door open, sending me crashing into the wall. Pain shoots up my right shoulder blade. It’s not broken, and I don’t tell my mom, believing in my childish mind that my punishment fits the crime.

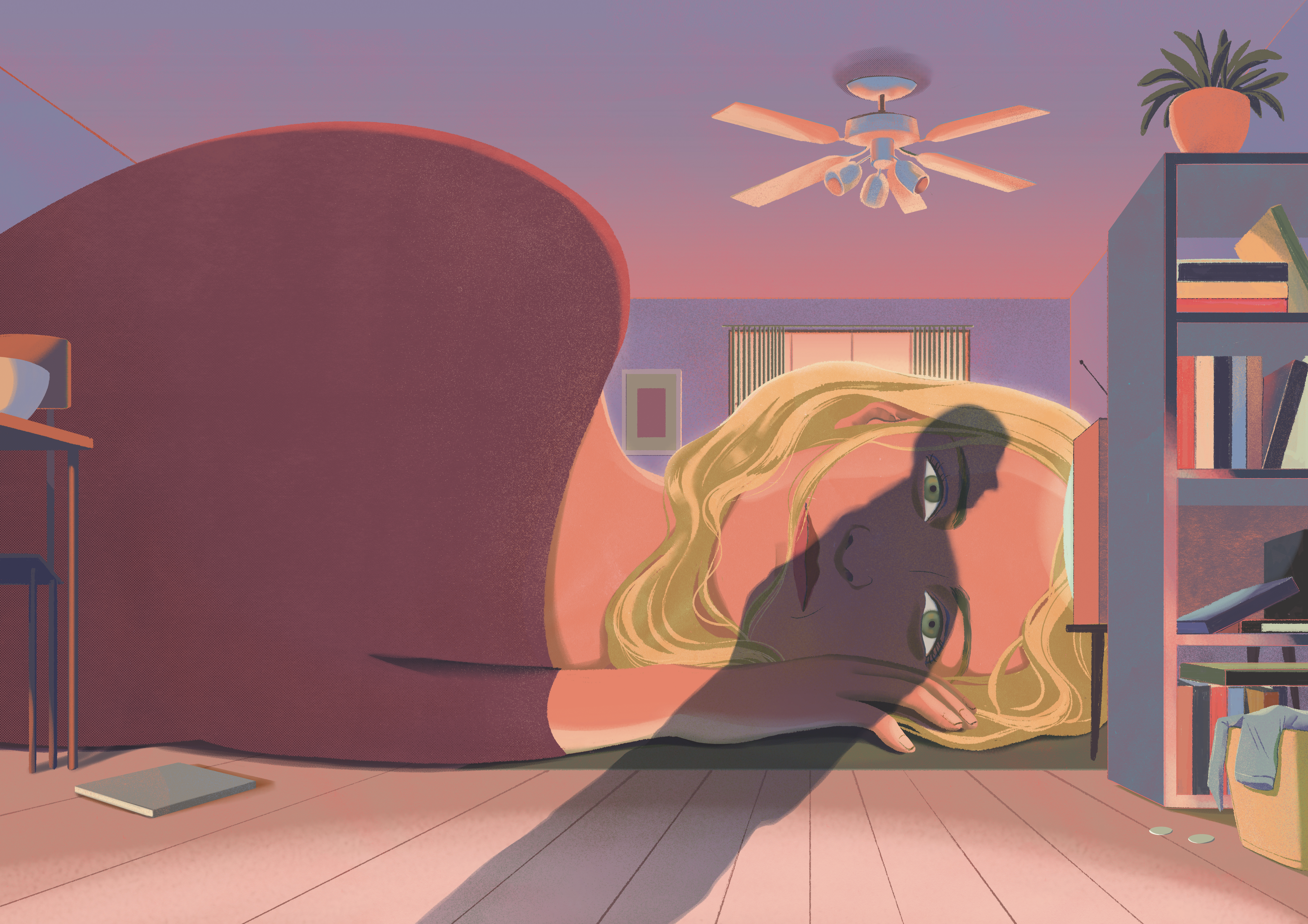

Though this is the first glimpse of your monstrous side that I can remember, it’s certainly not the last. The deeper you fall into addiction, the more your personality seems to change. A darkness comes over your face, like a storm moving over the horizon, whenever one of the moods hits. You get annoyed with whatever irritating thing I’m doing — not sharing with my brother, crying — or, sometimes, for no discernible reason at all. And then you snap. You scream and shake me, you threaten to “throw me through the f—ing window” or “give me something to really cry about.” You push me, toss me around, smack me and grab the scruff of my neck like I’m an animal.

Though this is the first glimpse of your monstrous side that I can remember, it’s certainly not the last. The deeper you fall into addiction, the more your personality seems to change.

I spend much of my childhood tiptoeing around you, trying to figure out what it is about me that inspires so much hatred and rage. Though you can direct your nastiness at my mother and brother, too, I seem to encourage it more than anyone else. For over two decades, I believe it’s because of some inherent deficiency within me that you can pick up on — a core atrociousness that others can’t see.

It’s only recently, with much hard work and therapy, that I’ve come to understand your fury has more to do with your addiction than with me. In fact, addicts in general tend to struggle with severe mood swings and aggression. In a 2012 article, Russian researchers assessed aggression levels in addicts based on their drug of choice. The study found that addicts in every group (including those like you — dependent on opioids, alcohol and weed) displayed significantly higher rates of anger and verbal, physical or indirect aggression than the control group.

But even during the years when your addiction is at its peak, you still embody so many qualities that make your mood swings all the more confusing. Your generosity doesn’t waver: you take my brother and me on surprise trips to the toy store, and outfit your cottage with snowmobiles, fishing rods, a boat and a trampoline. We’re constantly moving to bigger and better houses. You get us pets that always seem to like you best.

Despite your good intentions, you don’t consider the consequences of your decisions, another sign of opioid addiction. The toys and houses you buy are financed by money my maternal grandparents set aside for my education (which I’ll never see repaid). Whenever you’re short on cash, you have no qualms about rifling through the little red treasure chest where I squirrel away babysitting, birthday and Christmas money. You borrow money from your parents and your in-laws to cover mounting debts.

You often get so high that you pass out when you’re supposed to pick up my brother and me from school, leaving us to wait for hours in all types of weather. You and my mother fight constantly over money, your idleness — or me. Both sets of grandparents have secret conversations about whether my brother and I are safe in the house.

By 15, living with you is unbearable. I pray for my mother to leave you, for you to just disappear and, at my most emotional, for you to die. I give Mom an ultimatum: you or me. It’s complicated, she tells me.

Though I may not know the name of your sickness, it invades every corner of our house like a dark fog. Chronic use of OxyContin or other opioids slows the production of endorphins in your brain, meaning you have to take more and more to get the same high you’re used to. The parts of the brain that experience intense pleasure can actually hijack other systems in the brain (parts responsible for judgment, planning and organization), rewiring the addict to seek out the pleasure of getting high over anything else.

Since I’m a child, many aspects of your addiction are hidden from me. I don’t know if you ever grind down your pills to snort or inject them, have to doctor shop for multiple Oxy prescriptions or turn to the black market. I never see you use during my childhood, though I suspect there’s something wrong with your brain.

Sometimes, a few months will go by when I think something has changed. Your mood swings decrease and you still sleep a lot but you’re less prone to violence. Then, I’ll do something to set you off, and the dark side emerges again. When you aren’t trying to physically harm me, you like to sit me down to berate me for hours at a time, tormenting me with all of my failings — both real and imagined — until I’m nothing more than a shuddering mass of tears and snot.

The tightrope you keep our family balanced on finally snaps as your children hit their teens. I’m the first to fall. By 15, living with you is unbearable. I pray for my mother to leave you, for you to just disappear and, at my most emotional, for you to die. I give Mom an ultimatum: you or me. It’s complicated, she tells me. She has my brother to think of, she says.

She gives me two options: family counselling with you, or moving to an aunt’s in another city. Frustrated by Mom’s irresolution and terrified to be trapped in a room with you, I decide to go my own way and pack up my things. There’s no emotional goodbye between us or even a final confrontation. I simply leave, and I never come back. I spend the last year of high school couch-surfing and sleeping in suburban backyards.

By the time I’m in university, the house is up for sale. Through phone calls with your mother, I learn the toys, the vehicles and the cottage are all sold off. Years of reckless and irresponsible spending have finally caught up with you. It must be a devastating and humiliating time for you: watching our little suburban home grow empty, seeing the cottage you love so dearly inhabited by strangers.

Your son, now in high school, moves in with your parents, meaning you don’t manage to look after either of your children for the societally prescribed 18 years. I imagine it must kill you to say goodbye to my brother — you are two peas in a pod. He’s your little buddy.

Losing everything might provoke some depression but you mask it well, transforming it into anger by blaming your circumstances on the union, the recession and even your parents. If I know you at all, I have a pretty good idea of how you handle the emotions.

You and my mother move into the first of what will be a series of lousy rentals you have trouble affording. Years of addiction, domestic tension and financial ruin have placed a strain on your marriage. Mom tells you she loves you less and less as time goes by. You sleep in separate beds.

When you and I run into each other at family gatherings, I tolerate you. Nothing more. You are a little more successful with my brother, but even I can see his opinion of you dropping as he matures into adulthood. All those buddies you used to hang out with hardly come around anymore, busy dealing with their own addictions or moving on with their lives.

In early adulthood, I don’t fare much better. Though I manage the academic side of my undergraduate degree, my personal life is a wreck. In the summer of second year, I have my first severe panic attack in the middle of a shift at a restaurant job. By the summer of third year, I’m admitted to psychiatric intensive care, unable to manage my suicidal impulses. After everything, it feels like you’ve won. All I ever really wanted was to be with my mom, and you got her longer than I ever did.

Today, you’re in your early 50s, somehow still married, and you claim to be clean (except for weed). When you quit opioids varies depending on who you talk to. You tell your mother it happened in 2003, following a family vacation (though I would see your dark side many times after that trip). You tell your son it was in 2008, after he confronted you about your mood swings. I last saw you rage in 2011, during my one and only visit home. You spent two hours berating me about an addiction you thought I had (heroin, of all things — a drug I’ve never touched).

So even if you are telling the truth about your sobriety, I can’t believe you. After a lifetime of deception, I’ve learned you can’t be trusted.

I used to think our story was unique. But news headlines tell me we’re among many. The version of OxyContin you eventually became addicted to was taken off the market in 2012 and has been replaced by a supposedly abuse-resistant version. But Canadians are still suffering from opioid addiction — particularly with the emergence of fentanyl, an opioid that’s 20 to 40 times more potent than heroin, and 100 times more potent than morphine.

In 2015, one in five of Ontario’s public drug plan recipients filled a prescription for opioids. In 2016, more than 2,800 people in this country died suspected opioid-related deaths. In 2017, according to the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, nearly three percent of Canadians said they use opioids for non-medical purposes. So little girls and boys across the country are still growing up like I did.

I don’t know how to help those kids, people struggling with opioid addiction or even our family, but I do believe a lion’s share of the responsibility belongs to the health-care system and pharmaceutical industries. We need improved oversight and regulation around issues such as off-label usage and ensuring adverse reactions to new drugs aren’t going under-reported. Otherwise, there’s still a chance a patient could enter the hospital injured or sick, like you did, and leave with a blossoming addiction.

I want to let go of the mistrust, to forgive you, because fear has governed so much of my life. But it’s difficult. I’ve spent so long carrying around the trauma of your addictions and choices that I now suffer from acute anxiety. I can have a panic attack over something as simple as my partner pressing the car brakes too suddenly. I have flashbacks that I’m a child again and you’re attacking me. I’ve been hospitalized in psychiatric wards three times in the past seven years, where I was diagnosed with depression, anxiety and PTSD.

I want you to find peace as much as I want to find it for myself because, regardless of what you might think of me, I’ve grown into an empathetic person and I can’t stand to see any living creature suffer. And you’re still suffering. You’re onto your second hip replacement, and your stomach lining has worn away from years of drug abuse. And yet, you won’t take any responsibility for your decisions and actions that led you to where you are today.

I’m getting closer to finding peace. My third hospitalization connected me with long-term therapy and a group focused on overcoming trauma. My panic attacks and flashbacks are happening less often.

Unfortunately, your alleged sobriety and my improving mental health are not enough for me to mail you this letter or give it to you in person. I’m afraid it might be misconstrued and trigger the raging abuser I suspect still lingers below the surface, and who, despite everything, still scares me. Instead, I share our story with the hope that it might possibly nudge even one or two people who are suffering from addiction to reflect meaningfully on their habits and consider seeking help. Perhaps they could avoid experiencing some of the anguish we have.

Regards,

Your daughter

This story first appeared in the September 2019 issue of Broadview with the title “Letter to my opioid addicted father.” For more of Broadview’s award-winning content, subscribe to the magazine today.