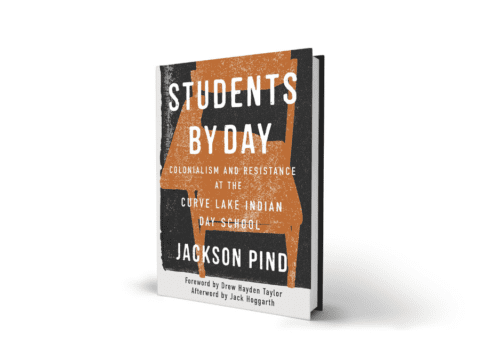

Eight years in the making, Jackson Pind’s Students by Day: Colonialism and Resistance at Curve Lake Indian Day School emerges from deep collaboration with survivors. A settler- Anishinaabe historian, Pind is an assistant professor of Indigenous methodologies at Trent University in Peterborough, Ont. In this conversation with Julie McGonegal, he explores the day school system, the resilience of survivors and how churches might foster reconciliation through data sovereignty.

Julie McGonegal: How did Indian day schools work?

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Jackson Pind: Day schools operated much like residential schools. The United Church ran at least 95, and the Roman Catholic Church over 325 nationwide. Teachers were employed by the church and reimbursed by the federal government. The key difference was that children returned home each night, as schools were on reserves. Yet the purpose remained the same: assimilation through forced English-language instruction and Christian teachings. Unfortunately, a lot of abuse took place.

JM: How did the Curve Lake day school come about?

JP: By the 1860s, a missionary company established what you could call a day school, focused on Christian teachings and English. In the late 1890s, the company folded its Canadian missions. This left a gap that the Methodist Missionary Society filled around 1899. It firmly established the day school and started mandating education through the Indian Act. By 1923, 40 to 50 students attended daily. The United Church operated the school from 1926 until 1978, when it returned to Curve Lake First Nation.

JM: What kind of education did students receive?

JP: Underfunding meant mostly unqualified teachers, often with 40 children in cramped classrooms. Communities requested better staffing but were denied. The lack of qualified staff was devastating; in 1923, no student passed the Grade 3 exams.

The Williams Treaty that year, written in English despite many communities not reading or writing in the language, stripped 25,000 square kilometres of land in central Ontario from First Nations and revoked hunting and fishing rights. Many historians now regard it as one of the worst treaties in Canadian history. The government knew that if it underfunded these schools, it could bring in these treaties without Indigenous knowledge or consent. The schools were a means of control — once they came in, the land was there for the taking.

JM: How did financial neglect affect students?

JP: The government tracked every penny, down to the cost of brooms, and delivered the cheapest education possible. For a lot of day schools, it was actually Indigenous people’s money that was withheld. Officials tapped into treaty trust funds meant for First Nations. In Curve Lake, the band council often had money for a better teacher and supplies, but they weren’t allowed to use it.

That legacy endures: today, schools on reserves in Ontario receive about $5,000 to $6,000 per student, compared with $12,000 to $13,000 in public schools. Over generations, that inequality compounds.

JM: Can you share the stories of one or two survivors?

JP: One was Valerie Whetung, who died in 2024 from cancer. She described abuse and early resistance — like asking a teacher if her dog would go to heaven and being mocked. She called it her “radicalization,” realizing the school’s teachings didn’t align with the teachings she was growing up with. She became an esteemed potter and community leader, founding the largest Indigenous health centre outside Ottawa.

Another survivor, Stanford Taylor, was taught to hate himself at the school. He went to prison soon after, spending nearly 20 years in and out before rebuilding his life. I sent him his transcript before he passed. He wanted to delete his swear words but ultimately decided to keep them, and that’s been meaningful for his relatives. You can tell that’s Stanford’s voice! For me, the responsibility is to tell the stories in a way survivors would be proud of.

JM: How is the community working to heal?

JP: The day school still stands. It houses kindergarten to Grade 3 classes, taught entirely in the local language and culture — a beautiful testament to survival and renewal. Language revitalization is a major focus.

There was also a federal class action lawsuit that wrapped up in 2019. The settlement process happened right in the middle of COVID-19, and survivors felt disconnected trying to apply online for compensation. There hasn’t been any TRC-type process, so that’s been frustrating.

This year, on Sept. 30 — Orange Shirt Day and the book’s release — the community gathered to talk about what comes next. Despite a system designed to erase their cultures and languages, they’ve endured. Their story is one of resistance.

More on Broadview:

- Colour the Trails helps racialized Canadians enjoy the outdoors

- Wab Kinew is just getting started

- How Qualicum First Nation woke up its language

JM: Did you face any challenges in accessing school records?

JP: One major challenge was Library and Archives Canada’s painfully slow PDF reader. I went through about 10,000 documents, each loading one page at a time. To solve this, my colleague Benjamin Farmer McComb and I built indiandayschools.org for searchable access. It’s had nearly 25,000 views. Library and Archives Canada has since launched a $625-million project to digitize six million more records.

The logistics of archives reflect a very colonial process. That’s still a problem. During my research, I spoke to Curve Lake’s cultural archivist at the time, who was frustrated by the United Church’s red tape.

It’s on churches and government to ensure the documents they digitize go back to the First Nations. The urgency is real: nearly 40 percent of the survivors I interviewed have already died. Returning these records while survivors are still here is critical.

Despite the challenges, I’m hopeful that churches and archives will commit to true data sovereignty, giving Indigenous nations full authority over how their records are stored, accessed, interpreted and stewarded. Every church should look at its local archive and ask what can be returned.

***

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. It first appeared in Broadview’s January/February 2026 issue.

Julie McGonegal is a journalist in Elora, Ont.