On the evening of Jan. 10, two weeks into Israel’s air and ground offensive in Gaza, the occupant of an apartment above a health clinic in the densely populated Gaza City neighbourhood of Shujaya received a phone call. It was the Israeli military, warning that the building was about to be destroyed. Fifteen minutes later, precision-guided weapons struck.

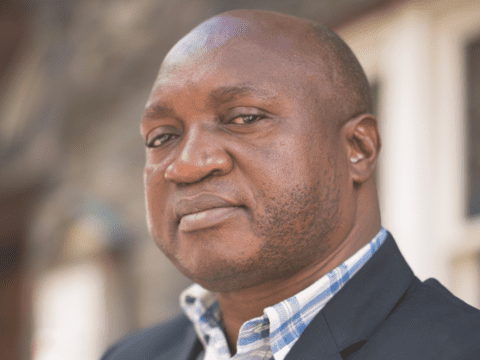

Later, news of the attack reached Constantine Dabbagh and hit him hard. Dabbagh is the executive director of the department of the Middle East Council of Churches that runs three primary-care health clinics in Gaza. One of them was the clinic in Shujaya. He had been celebrating Christmas in Bethlehem and couldn’t get home to Gaza because of the fighting. The word from inside Gaza was that no one had been hurt in the attack, but the clinic had been totally destroyed.

Many days would pass before Dabbagh was able to visit the ruins of the clinic — supported by the European Union and numerous church groups, including the Canadian ecumenical coalition Kairos, as well as the Canadian International Development Agency — to see if anything could be salvaged. Despite steeling himself, he was shocked at the extent of the destruction: “I cannot express how I felt,” he said after the visit. “I didn’t cry, but my heart was aching.

“We had a laboratory fully equipped for blood tests and ultrasound, and we had only just put in computers with a management information system. There was a six-week stock of medicine and water purification equipment, as well as milk and nutritional biscuits for the malnutrition program we run for children.

“All that was left was a heap of rubble and some papers from files blowing about in the wind. That was all. Nothing survived.”

The Shujaya clinic was among an estimated 4,000 buildings destroyed in Israel’s effort to root out Hamas and other fighters based in Gaza and put an end to thousands of rocket attacks that have been launched across the border against Israel in recent years. The Israel Defence Forces maintain that Hamas used buildings such as hospitals and schools to stage attacks.

Dabbagh insists that the Shujaya clinic was nothing more — or less — than a primary-care centre that provided a wide range of services, including pre- and post-natal care, general medicine, laboratory testing, dentistry, care for the elderly, family planning and health education, to some of the poorest people in one of the most densely populated patches of land on Earth.

He has become convinced that Israel wants “to make life in Gaza as difficult as possible. It was a matter of destroying the lives of the people through the facilities available to them, including schools and clinics.” He is not alone.

Amnesty International says the large-scale destruction of homes and other civilian properties amounted to “wanton destruction [that] could not be justified on military grounds.”

According to the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, 1,417 Palestinians died in the fighting, among them 313 children and 116 women. Israel disputes the figure, setting the death toll at 1,166 and claiming that more than 700 were Hamas or other “terror operatives.” Thirteen Israelis died, including four civilians and four soldiers who were killed by friendly fire.

A group of 16 of the world’s leading war crimes investigators and judges have urged the UN to launch a full inquiry into the gross violations of the laws of war committed by both sides in the conflict. Signatories include Archbishop Desmond Tutu; Mary Robinson, the former Irish prime minister and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights; and judge Richard Goldstone, formerly chief prosecutor of the international criminal tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. After Israeli forces withdrew in late January, United Church Moderator Rt. Rev. David Giuliano joined the primate of the Anglican Church of Canada in urging the Canadian government to press for an inquiry.

An inquiry could establish whether or not Hamas fighters were using the clinic as a base — a charge that Constantine Dabbagh categorically denies. If unfounded, the attack would give credence to his view that the real target was the people of Shujaya.

Urbane and elderly — the collar and tie he habitually wears to work at odds with the stringencies of life on a strip of land that has been called the largest prison camp on Earth — Dabbagh speaks with the passion of someone appalled at humankind’s capacity for destruction.

He was a child of eight when his family fled the port city of Haifa as the state of Israel came into existence. He has regarded Gaza as his home ever since, eschewing long ago the chance to join the rest of his family, who made new lives in Australia.

He is one of 3,000 Palestinian Christians who live in the Gaza Strip. “We are part and parcel of the land,” he says. “We are travelling in the same boat as our Muslim brothers and sisters. I will never leave.”

Measuring 25 miles long at its farthest reach and six to seven miles wide, the Gaza Strip is home to more than 1.5 million people living in Gaza City, several smaller towns and a series of refugee camps. (Outside of Africa, Gaza has one of the highest birth rates in the world, with the expected number of children born per woman now 5.2, based on 2008 data.) Gazans have been subjected to a permanent blockade by Israel since June 2007 when Hamas took control of the strip after coming to power in elections the previous year. Israel has said it would lift the blockade only if Gilad Shalit, an Israeli soldier captured by Hamas in 2006, is released.

On the shores of the Mediterranean, Gaza is bounded on two sides by Israel. To the south lies Egypt, which has proved only too happy to support the blockade of the territory, given the links between Hamas and its own homegrown, outlawed Islamist movement, the Muslim Brotherhood.

Every inch of the land border is now surrounded by a high-tech separation fence, which in some areas becomes a wall. Swaths of agricultural land on the Gaza side are designated by the Israelis a security buffer zone, which Palestinians enter at their peril.

The only goods allowed in or out by Israel are those deemed essential for humanitarian purposes. Even those can be delayed or turned back altogether. At sea, Israeli gunboats maintain the blockade, harassing fishermen and preventing them from reaching the deep waters where the fish are. Today most of Gaza’s fishing fleet stands idle.

Shujaya, the Gaza City neighbourhood where the clinic first opened its doors 40 years ago, is a highly populated district of labyrinthine streets and uniformly grey cinder-block apartment buildings. Paint and plaster are hard to come by because of the blockade and are too costly for most. The only splashes of colour are found on major thoroughfares, where green Hamas flags and shaheed (martyrdom) banners and posters — garish, computer-doctored photographs of young men who have died resisting the Israel Defence Forces — hang from electricity poles.

Streets are strewn with potholes because of Israel’s refusal to allow construction materials into Gaza for fear they could be used for military purposes. The children who play on the streets appear lively enough. But appearances are deceptive. In the eight months before its destruction, the Shujaya clinic had embarked on a program to determine the extent of anemia and malnutrition in children between six months and three years among the district’s 70,000 inhabitants.

Later, it widened the study’s scope to examine children between six months and five years. Records were held off-site and survived the bombing. They suggest that more than half the children in Shujaya and, by extension, in all of Gaza, now suffer from anemia and at least 10 percent are malnourished. The clinic was among other church-supported health-care facilities providing children with iron supplements and enriched and fortified milk — “in addition to anything else we can find,” says Dabbagh.

The clinic’s findings are consistent with a report from the International Committee of the Red Cross, leaked last November, which chronicled the “devastating” effect of the blockade.

Noting that 100,000 Gazans who used to earn their living in Israel are no longer allowed to travel there to work, it said alarming deficiencies in iron, vitamin A and vitamin D were now apparent in people’s diets. The report added that up to 70 percent of Gaza’s population was seeing “a progressive deterioration in food security” that was forcing people to cut household expenditures down to “survival levels.”

“Chronic malnutrition is on a steadily rising trend and micronutrient deficiencies are of great concern,” it warned.

The current blockade is the latest and most stringent in a long line of closures imposed by Israel as the security situation has worsened. Earlier this year, the medical journal the Lancet published findings of a study into maternal and child health in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. The authors warned: “Undernutrition is of particular concern in view of frequent births, short birth spacing, rising poverty and deterioration in the quantity and quality of food. The rapid deterioration in socioeconomic and political conditions has added a new sense of urgency as rising food prices, falling incomes and increasing unemployment jeopardize food security.

“Stunting, low height for age, which is an indication of chronic malnutrition and a risk factor for cognitive development, has been rising since 1996 and in 2006 was recorded in one in 10 children,” the report continues. “Although in the West Bank between 1996 and 2006 stunting increased (from 6.7 percent to 7.9 percent) it was especially pronounced in the Gaza Strip, rising from 8.2 percent to 13.2 percent.”

Today, about 80 percent of Gaza’s population depends on food aid supplied by local charities and the United Nations’ World Food Programme. Unfortunately, the food aid is not sufficient, says Dabbagh. “A family receives a certain quantity of calories to keep them alive, but they don’t receive all the food necessary for the body. They get dry rations and milk — they don’t get fresh vegetables and fruit.

“Produce is grown locally, but it’s very expensive. With 80 percent of people under the poverty line because unemployment is so high, people just can’t afford it.”

After the Jan. 10 attack, staff scoured the ruins of the Shujaya clinic for anything that might be salvageable. They unearthed the remains of a sterilizing unit and a blood analysis machine they hope might be useful for spare parts someday.

In a clear affirmation of how much the people of Shujaya valued the services the clinic offered, they are pitching in to rebuild it. A local contractor has offered a building he owns on the same street as the destroyed clinic. He has also offered to pay for a large amount of the conversion costs and track down many of the necessary materials. Much of the equipment that was destroyed has already been replaced by groups including the United Church-supported Action by Churches Together, Caritas (a Catholic relief agency) and the Pontifical Mission for Palestine, which has also said it will help pay for the conversion.

It is all hugely welcome, but Dabbagh still does not know how they will continue to provide free medicine. Where once patients met half the cost, Gaza’s economic plight means that few can now afford even a nominal amount.

Nonetheless, in late March Dabbagh was predicting that the clinic would be up and running in a month. “The community has felt our absence over the past three months,” he said. “People continue to ask when we are going to reopen.

“We need to find new funding for medicine. And when we open, we will also offer psychosocial help. It’s badly needed. Many people are still traumatized.”

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s June 2009 issue with the title “Reduced to rubble.”