A massive painting of the Transfiguration hangs at the top of the stairs off the side entrance of Broadway Church in Kansas City, Mo. When my eyes adjust, I realize that I am totally surrounded by a variety of artistic renditions of one of the Bible’s chief mystical events, the moment when Jesus metamorphoses into radiant light on a mountaintop.

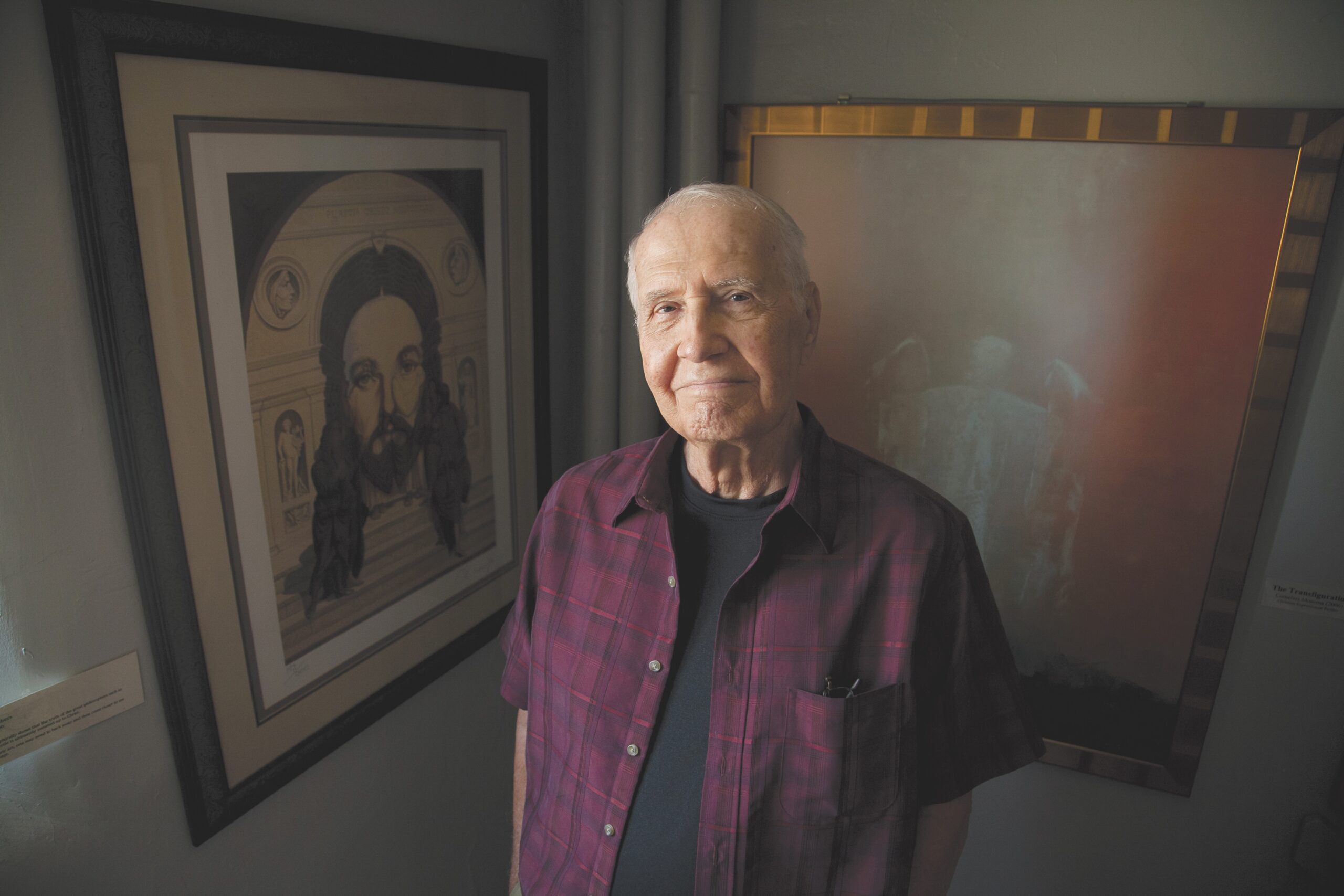

Rev. Paul Smith, Broadway’s recently retired minister of 49 years and the author of Integral Christianity: The Spirit’s Call to Evolve, greets me with a large magnetic smile and shows me around the Faces of Jesus gallery on permanent exhibit at the church. At the end of the tour, we wind up back in the Transfiguration section. “The Transfiguration is the most important event in Jesus’ life, more significant than the Resurrection,” Smith says. “It’s transformation through deep spiritual experience. Jesus’ spiritual and psychic energy became so radiant that they were visible to those around him. He was having conversations with dead men. He was also a telepath and an energy healer.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Integral Christianity, Smith’s unique blend of progressive theology and mystical experience, is making waves. Drawing on the work of Ken Wilber, the highly praised and oft-criticized American integral philosopher, Smith has placed Christianity on the integral map and set a course for Broadway to become a truly integral congregation, the first of its kind.

Understanding Smith’s work means getting a handle on Wilber. Easier said than done. Wilber’s complex writing has given rise to a multiplicity of descriptors of the man himself: “transpersonal psychologist,” “new-age cult leader” and “Einstein of consciousness.” Love him or hate him, his work is respectfully ambitious.

In a nutshell, Wilber’s theory is an effort to integrate knowledge from all cultures, major civilizations and fields of human inquiry, identify common patterns and distill their best elements into a life map that Smith calls “the most advanced life-positioning system available today.” Incorporating systems of knowledge from ancient sages to modern scientific gurus, Wilber has extracted five factors that facilitate human evolution. Framing these in terms of spiritual growth, Smith writes in Integral Christianity that the goal of the integral church is to “create a community where the members can accelerate their growth in (1) stages of understanding God, (2) states of consciousness in experiencing God, (3) standpoints in relating to God as Jesus did, (4) shadow work and other forms of inner healing . . . and (5) steps of practicing that lead to transformation.”

The sanctuary at Broadway feels like my favourite pair of jeans — worn and comfortable. The pews and pinkish carpet show their age. As the praise band warms up on stage, congregants mill about, greeting each other with hugs, pouring themselves a cup of coffee at the entrance. Colourful dyed banners adorned with butterflies hang above the pews. The bulletin cover reads, “Where Souls Wake Up.”

Wanda Heatwole, the church’s music director who doubles as the main worship leader, invites congregants to open their hearts to the Spirit. She strikes a singing bowl from where she sits behind the grand piano, slowly tracing the bowl’s circumference. The pitch pierces my chest more than my ears. Later, Heatwole tells me that the vibrations correspond to the chakras (energy nodes in the body) and are meant to penetrate us in particular areas.

Cognizant of the body-spirit connection, David Hunker, the church’s worship co-ordinator, says that one of the distinguishing features of worship life at Broadway is the number of songs. “We use music to help people move from their left brain to their right brain, so we sing a lot, especially at the beginning,” he explains.

I count six pieces of music in the first 20 minutes, each stamped with Smith’s theology. Around me, some congregants hold their arms outstretched as they sing of the infinite God, draw their hands together in prayer posture as they address the intimate God and cross their hands over their chests as they sing of the inner God. It is the most transparent example of integral theology embedded in the worship experience.

“The traditional understanding of Trinity leaves out you and me. There is God as being, God as Jesus, God as Spirit, but how about God like you and me, where God is not a being but being itself?” asks Smith as he sits across from me on a loveseat in the church library, surrounded by theology books.

Smith has reformulated traditional Trinitarian notions, recasting them as the infinite face of God (the God large enough to create and evolve the cosmos), the intimate face of God (who comes to us like a loving parent) and the inner God (the divinity within).

“I believe we must intentionally adopt more evolved mantras to enlarge the beautiful, true and limited idea of traditional Trinity,” Smith says. “We desperately need a more inclusive linguistic framework that fits with a fuller understanding of who Jesus was and what he taught us. I think this notion of the three faces of God is the greatest breakthrough since the Trinity.”

Twenty-five minutes into the service, Heatwole invites congregants into a quiet reflection time to listen to God speak to us. It takes me a while to settle into the silence. Then I hear internally, “Claim yourself. Claim me.” For weeks afterward, I would mull over the meaning of those words. Later at the communion table, the server says, “I see the light in you” as he hands me the bread. Rather than a sermon, there is a “teaching time,” during which Sheryl Stewart, a congregant and retired teacher, reflects on “being salt.”

Spiritually fed, we file into the hall of the church basement for lunch. Each week, volunteers prepare a full meal. Today it’s chicken, rice and beans, plantain and cake. Looking around, I notice there are a high percentage of middle-aged men. “That’s because we are a gay-friendly church,” explains Hunker, who had left the church and returned after he came out. “It’s hard to describe, but it’s like I forget that I’m gay here. It’s a relief that I don’t have to think about it when I come. It’s such a non-issue.”

It wasn’t always this way. The congregation split numerous times throughout the course of Smith’s pastorship, sparked by controversies over small-group ministries, moving to contemporary worship and encouraging the leadership of women, for example. Yet every time the church lost members, it attracted new ones. Over 25 years, the congregation tripled in size. “I was the guy who was always invited to church conferences to teach congregations how to grow. But it was so fake, so phony, so nothing,” says Smith.

In 1997, half the members left over the “gay issue.” There was a congregational vote to terminate the entire staff team. “I managed to hang in. [Those who campaigned to oust me] had originally come to Broadway because we had evolved beyond the traditional church. They liked that. But they didn’t like the fact that my vision was not limited, short-term evolution. It was evolution forever!” reflects Smith. When the remaining congregation voted to become gay affirming, it was kicked out of the Southern Baptist Convention.

Smith catalogued his ministry struggles in a chapter called “Leading Change and Causing Trouble,” which he published on his website (www.revpaulsmith.com) because his editors thought it was too negative to include in his book. He writes, “What institutions do best is defend themselves against change. . . . What can we expect of our religious leaders in moving our churches into higher levels? Often, not much! The pastors, staff members, priests, bishops, denominational personnel, seminary professors, and lesson writers of our faith and churches are most often in their positions because they are not change agents. . . . They were hired to preserve the religious institution, not change it.”

What has Smith learned about change management? He pauses. “I don’t know. I’m just pushy. I push it to the breaking point, which gets the job done. I had to struggle, but it was good for me. You need to leave it all in God’s hands. Institutions come and go. I think the whole professional [ministry] system mixes up the spiritual leader’s job with their spiritual growth, and I just made the decision not to limit mine.”

Broadway takes the “priesthood of all believers” concept to heart. Smith took his name off the church sign, erased it from the bulletin and intentionally fostered team leadership. “I’m not much for ordination because it’s a false distinction,” he says. “We need to recognize our leaders, but there is a false distinction between the spiritual and unspiritual. Everybody’s ordained to use their spiritual gifts, whatever they are.”

I’m sitting in a coffee shop with a handful of Broadway’s key leaders, most of whom Smith mentored. We’re discussing their leadership roles and what makes the church integral. “I would say that we aren’t really ‘integral’ yet. We are integrating,” says Edgar Tanner, a member of the ministry team hired on a temporary basis after Smith left. There are nods around the table and consensus that ongoing evolution is key.

“As a church, we’ve learned to move forward with things and reject what we used to believe, and the commitment to evolve, to move to the next stage, is part of what makes it integral,” comments Rev. Marcia Fleischman, Broadway’s senior pastor. (The church broke with its earlier aversion to hierarchical ministry and appointed Fleischman in a lead role to make a statement about women’s ministry in the conservative southern United States.)

“The other thing that makes [Broadway] integral is going deep into spiritual exploration,” Fleischman adds. “We’ve done a lot of work with the Enneagram [a personality framework]. We have spirituality workshops. We have what we call ‘Experiencing God’ sessions once a month, where we take turns sitting in the centre of the circle as people pray for us and interpret what they think God is saying to us.”

Fleischman sees visions of angels in her prayers, painting them on giant canvases that hover over the front doors leading into the sanctuary. “I entered into the church through the charismatic growth period. Paul spoke in his prayer language, and my spirit just blossomed. I realized there is a transmission of the spirit to one another,” she says.

For integral Christians, transcendental experience that leads to deeper awareness is the cornerstone of spiritual evolution. Many progressive Christians are embarrassed to pray and don’t know what to do with mystical aspects of religiosity, Smith says.

“Christianity then becomes a matter of social stance, like [believing in] inclusivity and [that] ‘Jesus was a good teacher.’ We need to keep that and add back in that Christianity began as the experience of a mystic having experiences with God, and those experiences were transferred to his disciples.”

Smith had his first spiritual experience when he was 23, two weeks after a small group of charismatic Episcopalians prayed for him. He describes the feeling as a profound sense of love. Later, when he discovered integral theory, he found himself in the company of Buddhists (Wilber and many of his followers are Buddhist).

“They sat for an hour every day in meditation,” Smith says. “Good God! I had a little prayer in the morning and went on my way. So I got serious about praying and meditating.” His prayer practices have included meditation, brainwave entrainment (listening to musical tones to enter progressively into deeper brainwave states) and visualization.

Restoring prayer to “trance prayer” is one of the goals of integral Christianity, Smith says. Some progressive Christians “see prayer as good thoughts, but they don’t see it as an altered state of consciousness.” Smith tells me he experiences visions and has a profound sense of spirit guides, including Jesus, whose hand he feels on his arm. “It’s good to subject things to the rational but not be limited by it. We’re trying to introduce post-rational, not pre-rational, spirituality that is evidence-based, experience-based and produces genuine changes that are shown by greater love, inclusivity and morality.”

Lunch over, I follow about a dozen or so people into a class called “Adult Relationships: Understanding Old Wounds, Healing Original Attachments, Loving and Living Well,” led by a psychotherapist connected to the congregation. The room quiets as we begin charting our early childhood experiences on paper and then listen to a lecture explaining the impact of those primary experiences on brain function.

The class fits into Smith’s vision of shadow work, the necessary inner work one does on personally painful aspects of life in order to move through states of consciousness. Toward the end of the session, a young woman admits that she is a better parent with her second child and that she’s going to do the exercise with her eldest to help repair the damage she caused; she came to the church for the therapy. “I feel better after I leave,” she says. I left feeling enlightened, too. Certainly more spiritually and emotionally awakened than when I walked in.

The Sunday experience at Broadway was the total package: meaningful worship including solid teaching, excellent music, space for quiet meditation and deep listening in a relaxed, creative and clearly socially progressive space, followed by a lively community meal and revealing self-work. With just 50 people in attendance, the congregation is numerically a shadow of its former self, but I don’t doubt what Smith says: “We are at a deeper, more profound, more alive place than we were back when the pews were full and we had multiple services.”

Smith thinks the integral church is a particularly good fit for those of the “spiritual but not religious” ilk who have outgrown their religion. Other modern church movements, he adds, tend to discount the value of experiencing God in transcendent states of consciousness and tapping into one’s own inner divinity. As the Apostle Paul puts it, “I live, yet not I but Christ lives in me.”

Is Broadway Church the way of the future? And if integral Christianity espouses spiritual evolution, is there something beyond even it? “I’m not sure what post-integral looks like, but I think it probably involves more transcendence and more of the mystical,” says Smith. “Integral does a good job of understanding systems, but the final frontier is the spiritual frontier: transcendence, inner life, spiritual realities. We explored outer space. Inner space is what’s left.”

Rev. Trisha Elliott is a minister at City View United in Ottawa.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s September 2014 issue with the title “‘Where souls wake up.’”