Gustav Klimt painted the Beethoven Frieze directly on the walls of Vienna’s Secession building for a 1902 exhibition. The massive mural — a little over two metres tall and 34 metres long — is the artist’s version of the composer’s Ninth Symphony. Parts horrific, absurd and ultimately moving, it is a battle of good and evil, of pure hearts and selfish desires, that ends with a female choir singing the Ode to Joy.

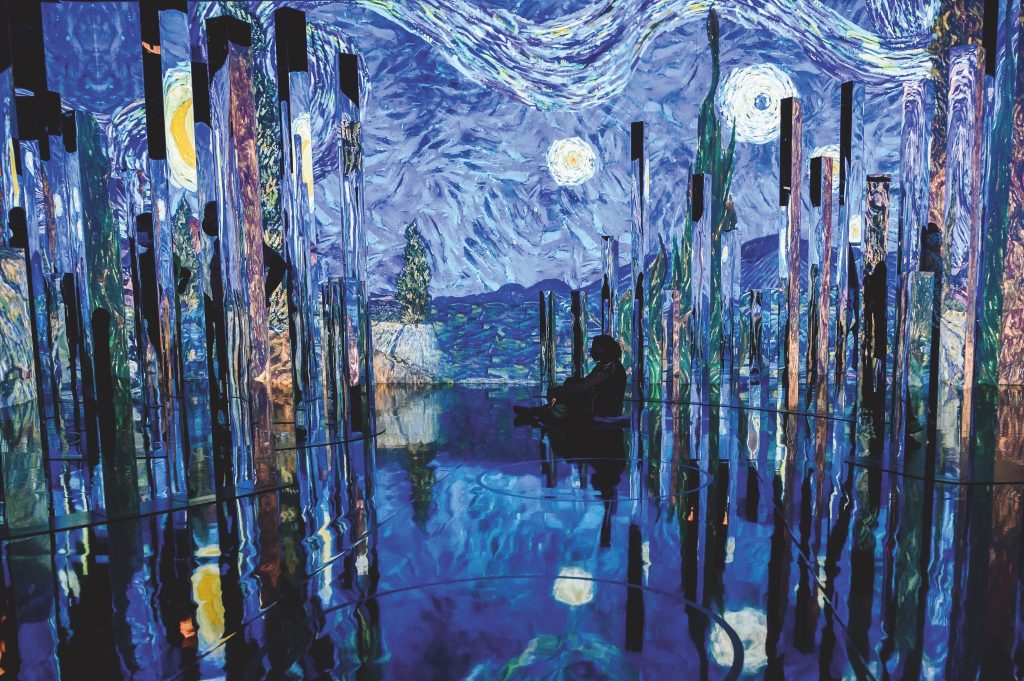

Immersive Klimt: Revolution, the half-hour video installation that opened in Toronto last October, represents this magnificent and much-debated work in a few minutes. Like other such shows featuring Monet, van Gogh, The Nutcracker, even magic and dance, the Klimt is housed in a massive warehouse-like space, with images flashing on four towering walls and the floor, showering visitors in 90 million pixels and 60,600 frames of video.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

The pixelated Beethoven Frieze begins where the original mural ended, with the choir filling all the walls, one woman at a time. Assorted other images then dissolve and morph, creating a story that references Klimt but is not his. This new interpretation is the work of Massimiliano Siccardi, a former dancer turned theatre artist. He is also the creator of Immersive Van Gogh, which debuted in Toronto in the spring of 2020, and of Frida: Immersive Dream, which opens this month. The proliferation of these shows speaks to their popularity. While not quite the real thing, they still have a distinct sensory appeal.

“An immersive show is like what happens to you as a child,” Siccardi said in an interview last year with Newcity Art. “As kids, you are always getting kidnapped and brought into another dimension. Everything is incredible. You see things that are bigger than they really are and later in life you wonder how you imagined them so big.”

In his Immersive Van Gogh, flowers from the Dutch artist’s paintings are projected hundreds of times their size on the walls, in surround. They blow in the wind. They open and close, grow large, dissolve, appear again in a different size. The viewer is dwarfed by them. These video animations belong to Siccardi; they are his flowers now, not van Gogh’s. A fine brushstroke converted to a vivid wall of colour to overwhelm the viewer.

Beyond Monet, which opened in Toronto last September, is designed by the Normal Studio, a Montreal multimedia company. (The studio launched Beyond Van Gogh in Hamilton this January, which is not to be confused with Siccardi’s van Gogh.)

The Monet installation starts with a train — digitally manipulated out of Claude Monet’s paintings — leaving Paris, moving from town to country, chugging along, blowing steam across the walls. It stops at meadow scenes; there are ladies in parasols. The sequence ends with a quotation from Monet, and another sequence begins. For half an hour, pixels dance on massive walls and the ceiling. The sea roils, the lilies glisten, snow falls. Paintings dissolve into each other with the frenetic energy of a music video. The viewer is immersed in impressions of Impressionism.

The last sequence is a series of Monet’s greatest hits, ending with multiple quotations from Monet that read like affirmation memes: “All I did was let my brush bear witness to what the universe showed me.”

Monet fought for beauty in the face of ignorant critics. Just like van Gogh, who in Don McLean’s famous song Vincent is elevated to a resurrecting god who died for our parochial sins: “How you suffered for your sanity / How you tried to set them free / They would not listen, they’re not listening still.”

The immersive Klimt show is called Revolution. It begins with scenes from a Vienna opera house, suggesting a rigid formal society that Klimt will come along to challenge with his bold style and sinuous bodies.

More on Broadview:

- ‘Night Raiders’ shows the power of sci-fi and horror to illustrate Indigenous experiences

- Ivan Coyote’s new book is a study in the healing power of letters

- Shalak Attack sees her murals as a ‘more democratic way of using art’

Pixels, of course, are not paintings. The radicalism of the original art has been repackaged for mass consumption. Perhaps that is why the reviews for these immersive shows are often negative. Sure, it is always better to see the actual works if you can, but that requires a financial privilege few can afford. And sure, there is something cheesy about these shows: they are loud, forced morality plays.

Digital immersions may not be subtle, but they are powerful, in their own way. Images pulled from famous paintings, a face here, a tree there, set to music, displayed large, in the round, are a rich sensory experience. There is the beauty of the pictures, the pull of the music, the power of the size. It is immersive, but it isn’t anything new. Anyone who has been in an IMAX theatre, watching a sled racing down a hill, has felt their stomach turn with corporeal sensation. There have been Cineramas and surround sound and countless other tricks to help us feel awe.

Monet’s Water Lilies are very large paintings. Measuring two metres high and 13 metres end to end, the three of them encircle the viewer at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. This is how Monet wanted these paintings displayed. He called them “grandes décorations.” There are 22 of these works at Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, in two large round galleries. The experience is overwhelming. The paintings are calming. You can walk up to them, see the brush strokes, the subtle mechanics of painting, or step back, as I often prefer, to see a wash of colours, reflections, layers.

Immersive shows have video edits and special effects instead. And for the while you’re there, you can drown yourself in image and sound. But in the way you would not confuse Klimt’s frieze for Beethoven’s Ninth, do not confuse these installations with the artists’ works. That is not Monet or van Gogh or Klimt on those warehouse walls. It is instead a fast-moving interpretation of those artists. A digital kinesis instead of a painting’s contemplative quietude.

Of course, art galleries and museums can be precious. Art connoisseurs can be pedantic. A painting, by a master or an unknown, is a visceral experience. Not merely spiritual or contemplative, but also of the body. The Beethoven Frieze took my breath away. I look forward to the Monet room in MoMA whenever I’m in New York City. I want to step into each painting. I want to embrace the beauty.

Immersive shows are an ersatz experience, and that is better than none.

***

This story first appeared in Broadview’s March 2022 issue with the title “A full-bodied experience.”

Andrew Faiz is a writer in Toronto.

Andrew Faiz, thank you for your superb enlightenment on paintings and music and their motivations. Your article is truely a masterpiece in itself. I want to read more of your well thought out and considered

writing.