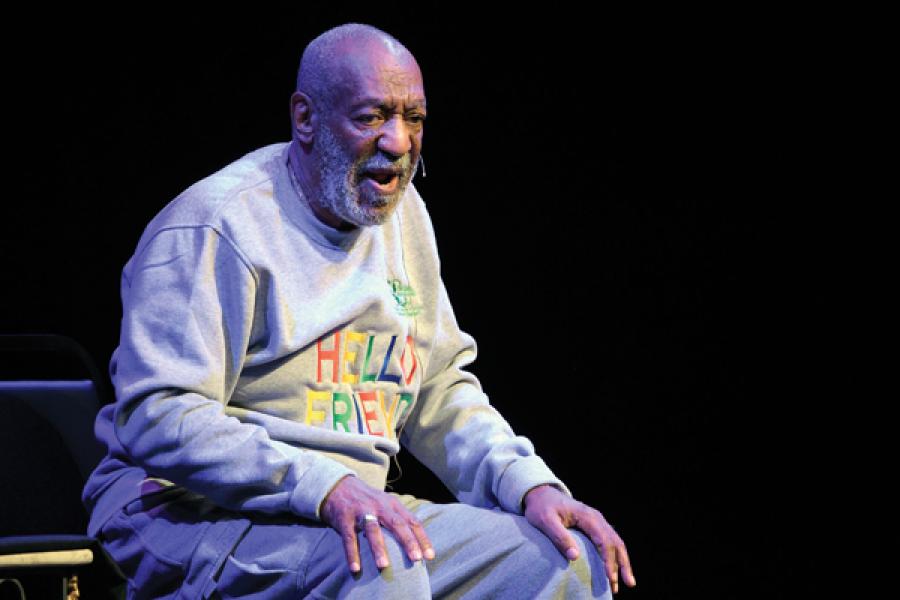

Bill Cosby is within close enough range that I could sail a paper airplane at his head and be reasonably certain I’d hit my target. It’s early January, and I’m sitting in the centre of the second row at Hamilton Place, where Cosby is set to appear for his third and final Canadian performance, part of a North American tour continuing until this June. Fourteen theatres have already cancelled his show due to the storm of ongoing publicity surrounding the allegations of 30 women who claim he drugged and sexually assaulted them. While there have been a few small demonstrations outside his shows, no group has ventured inside the protected bubble of the concert halls where he continues to be adored.

Until now.

Sitting beside me is Christina Miller Paradela, a diaconal minister at Rock Chapel and Lynden United churches in Hamilton. She is chatting amiably with the young man next to her, and I draw strength from her calm presence. She isn’t the only minister in the audience. Somewhere behind us is Rev. Ian Sloan, minister of New Vision United in Hamilton. The three of us are part of a group of 30 women, men and teenagers — one to represent each of the women we believe Cosby has victimized.

We are scattered throughout the orchestra level, awaiting the 15-minute mark in the show when we will stand in unison to disrupt Cosby and demonstrate our support for his accusers. I’m in disguise with a long, dark curly wig covering my blond hair. After doing a lot of publicity about the protest, including TV appearances, I’m recognizable and don’t want to risk being turned away at the door. Under old coats — which we will leave in our seats — we are wearing white T-shirts emblazoned with the words “We believe the women.” Tucked under our clothes are posters with the same words. Rape whistles dangle around our necks and will soon pierce the air, sounding an alarm that we believe a dangerous man is on stage. Cosby is aware of our protest and has taken precautions. More than two dozen uniformed security and police officers roam the aisles surrounding the rows of half-empty seats.

Cosby speaks reassuringly to the audience in the tone of a kind and tolerant grandfather: “Whatever happens here tonight, if there’s some sort of outburst, we just have to remain calm and things will be taken care of. It oughtn’t last that long.” He salutes the 100-plus protesters gathered outside the theatre before the show on this freezing cold night, even acknowledging their “human spirit” for standing up for what they believe in. In the next breath, he dismisses them: “In two years when I’m back, they’ll be inside.” He starts with a joke about stealing from the collection plate when he was a boy. So as not to arouse suspicion, we “fake clap” when the audience applauds, soundlessly banging the heels of our hands together.

We feel watched. We are nervous. But we are ready.

Allegations against Cosby of drugging and sexual abuse have been public knowledge for a decade, ever since Andrea Constand, who now lives in Canada, filed a civil complaint against him backed by 13 other women; Cosby eventually settled the case out of court. But the controversy re-ignited late last year when a YouTube video of standup comic Hannibal Buress went viral. Buress accused Cosby of having the “smuggest old black man public persona. . . . He gets on TV: ‘Pull your pants up, black people. I was on TV in the ’80s! I can talk down to you because I had a successful sitcom!’ Yeah, but you rape women, Bill Cosby.” In the weeks that followed, more than a dozen new women came forward with remarkably similar tales of harassment, drugging, molestation and rape. TV Land dropped reruns of The Cosby Show, and NBC cancelled a planned new Cosby sitcom. A few people came to his defence, among them Cosby’s real wife, Camilla Cosby, his TV wife, Phylicia Rashad, and his old friend Hugh Hefner, kingpin of the Playboy Mansion, where Cosby has been a frequent guest.

Cosby, for his part, remained silent. Except when on stage. There he continued to find audiences to enthrall. In late November, as accusations against him reached their peak, a Florida audience greeted him with a standing ovation.

A few weeks later, Cosby is slated to appear at Hamilton Place, a venue where I’ve watched legends such as Anne Murray, Gordon Lightfoot and Harry Belafonte perform, where I’ve brought my daughters to see Raffi and The Nutcracker ballet. I imagine Cosby walking on stage with impunity. I wonder how victims of sexual violence in Hamilton will feel about that. I wonder why somebody doesn’t do something. I wonder why that somebody shouldn’t be me.

I call Scott Warren, general manager at Hamilton Place, and beg him to cancel Cosby’s show or at least offer refunds to people who, in good faith, purchased tickets weeks before these new allegations. No dice. Cosby’s concert promoter has rented out the theatre, and if Hamilton Place breaks the contract they’d be on the hook for “a lot of money,” says Warren. I ask him if he has kids. He does. I ask him what kind of world he wants them to grow up in. His hands are tied, he says.

I am so angry I tell my husband I’m going to buy a ticket to the show and scream “Rapist!” at the top of my lungs — and I demonstrate for him the decibel level I plan to reach. He looks at me as if I have a fever. I guess in a way I do. When I calm down, I hatch a different plan, enlisting a few friends to purchase tickets to the show. I consult with a civil disobedience expert and a criminal lawyer on how we can stage an effective but peaceful protest inside the theatre without risking arrest or inciting an angry mob. I’m a 52-year-old middle-aged mom who has never done anything like this in her life. But this is one of those times I can’t keep quiet; fortunately, there are others who feel the same way.

The media caught wind of the story, and I do dozens of interviews with all of Canada’s major newspapers and radio and TV stations. The publicity fuels donations of tickets from people who no longer want to go to the show. The publicity also catches the attention of Andrea Constand, whose sister calls me at home late one night to say Constand wants to thank those involved in the protest for believing her.

The headlines about the protest also bring out the haters, most of whom hide behind anonymous online comments such as these: “If Bokma opens her yap in the auditorium the hundred[s] there to enjoy the comedy icon will put her in her place quick and proper.” “All men who go to that show should be ready to shut those man-haters down.” “If I am there and she does anything I will willingly toss her ass out.” “Stupid bitch.” “Leave [the] old man alone, if he dies of stress . . . his death will be on their hands.”

Someone posts my e-mail address online, and the vitriol spills into my inbox. I’m accused of “comedic terrorism” and told to “go to Afghanistan to get some perspective.” Luisa D’Amato, a columnist at the Waterloo Region Record, writes that our protest efforts “reek of elitist contempt for the ability of individuals to think for themselves.” I get into a heated argument with a man at a party who says Cosby’s accusers are opportunistic starlets in search of fame and money. I ask him to name one woman who’s gotten rich from being raped.

The same arguments against our protest are repeated over and over: “But he hasn’t been convicted of anything!” “But why didn’t these women go to the police?” “But it isn’t fair to the fans who want to see his show in peace!” “But women lie about rape!”

For some, it’s just too difficult to let go of the image of Cosby as the kindly Dr. Huxtable. Instead, they choose to believe these women are liars and schemers, all in cahoots to take Cosby down. But believing Cosby is innocent requires taking the word of one powerful man over the word of 30 women who did not know each other at the time of their alleged assaults and whose pattern of abuse shares strikingly consistent details. This isn’t a case of he said, she said; it’s a case of he said, she said times 30.

People want proof from these women. But where is the “proof” when there’s no weapon and no witness? Where is the proof of injury if you’ve been drugged and you aren’t even sure what’s happened to your body, yet you know in your bones that some kind of damage has been done? The court system — in which victims can have their credibility attacked while the accused has the right to remain silent — can’t be the only arbiter of truth in these cases.

One in four North American women will be sexually assaulted at some point in her lifetime. Yet over 90 percent of victims do not report the assault to police, according to Statistics Canada. Stigma, shame and blame and the fear of not being believed can keep women quiet for years. In a 2009 Statistics Canada survey of victimization, 472,000 women self-reported a sexual assault in the previous 12 months; in 2011-12, there were 1,610 guilty verdicts for sexual assault. False charges make up two to four percent of rape cases, no more than other types of reported crimes.

Back in my seat at Hamilton Place, I hear the first rape whistle, our signal to stand together. We peel off our coats, unfurl our posters, hold them high over our heads and rise up, chanting, “We believe the women!” over and over, punctuated by the intermittent squeals of whistles, which echo throughout the theatre. Very slowly, we make our way toward the aisles. The audience boos loudly and some shout out, “We believe Cosby!” Cosby, for his part, appears to be in complete control. When some in the audience yell at us, he says, “Please don’t. Stop. Calm. It will calm.”

Emboldened by the fact that the police and security guards are parting a path for us — not a single one approaches us — we chant louder and blow our whistles harder. A man who has put his leg on the seat in front of him blocks one in our group from getting out to the aisle. A police officer tells him to move his leg and escorts her out.

We converge in the lobby, exhilarated by the smooth execution of our protest. It lasted all of 10 minutes, but it made an impact. We emerge onto the street jubilant, barely feeling the winter cold in our T-shirts and still shouting, “We believe the women!” There are waiting reporters, and I rip off my wig and make a statement about how our protest represented a small disruption in Cosby’s show compared to the major way he’s disrupted his alleged victims’ lives. Then we all gather at a bar across the street to celebrate. We cheer when a clip of our protest airs on CBC’s The National, projected on the bar’s big-screen TV.

The next day, our small act of defiance makes international headlines, including in the New York Times, the Washington Post and Britain’s Daily Mail. Cosby’s boldly touted “Far From Finished” tour continues to fizzle as more venues cancel. Since the beginning of this year alone, seven new women have come forward with accusations that Cosby drugged and assaulted them.

While the protest is a victory of sorts, what has stayed with me most is the fact that it prompted so many women in my circle to share stories of harassment, molestation and sexual abuse that they had kept quiet for a long time. One friend tells of literally being dragged off the street by a man when she was a teenager. Another says something terrible happened to her when she was 12, and she still can’t talk about it. Yet another reveals that her Brownie leader’s husband molested her when she was six. On and on it goes.

Nothing like that has ever happened to me. The closest was a time when I was 16 and travelling alone on a bus. An older man sat beside me and pushed his thigh hard against mine for the hour-long trip. I sat there, stuck to my seat, hoping the bus driver would catch the plea in my eyes when he looked in the rear-view mirror. I was raised not to make a fuss.

Thank goodness that’s changed.

This story originally appeared in the May 2015 issue of The Observer with the title “The Cosby showdown.”